Difference between revisions of "Functional diversity in marine ecosystems"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

{{ Definition| title = Functional diversity | {{ Definition| title = Functional diversity | ||

| Line 114: | Line 113: | ||

Nekton are almost exclusively predators. The smaller species like the zooplankton are both predators and grazers. Plankton are therefore also classified by size, although there is again an overlap as many species will change to a larger size class as they grow older. | Nekton are almost exclusively predators. The smaller species like the zooplankton are both predators and grazers. Plankton are therefore also classified by size, although there is again an overlap as many species will change to a larger size class as they grow older. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Related articles== | ||

| + | :[[Measurements of biodiversity]] | ||

| + | :[[Marine Biodiversity]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:30, 4 March 2024

Definition of Functional diversity:

The value and range of functional traits that contribute to ecosystem functioning[1].

Functional group: Groups of species with similar ecological roles/functions. This is the common definition for Functional diversity, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

Functional diversity

Functional diversity refers to the variety of biological processes, functions or characteristics of a particular ecosystem in this case the marine ecosystem.

[2]Functional diversity reflects the biological complexity of an ecosystem. Some scientists argue that examining functional diversity may in fact be the most meaningful way of assessing biodiversity while avoiding the difficult and usually impossible task of cataloging all species in marine ecosystems. By focusing on processes, it may be easier to determine how an ecosystem can most effectively be protected from human disturbance. Protecting biological functions will protect many of the species that perform them. However, the exact function of most of the species is hardly known to date.

Functional diversity increases the overall productivity of an ecosystem by allowing for an increase in niche occupation - the way a species matches the specific environmental conditions within a habitat in interaction with other species. Functional redundancy occurs when different species fulfill the same role in an ecosystem (thus filling the same functional niche); it is in some way the opposite of functional diversity. Functional redundancy contributes to ecosystem resilience. Higher species diversity can lead to an increase in overall ecosystem productivity, but does not necessarily insure the security of functional overlap. In ecosystems with high redundancy, losing a species (which lowers overall functional diversity) will not always lower overall ecosystem function due to high functional overlap.

Functional groups

A functional group is a set of species that share alike characteristics within a community and therefore often share an ecological niche. Species sharing an ecological niche generally have similar structures in order to achieve the greatest amount of fitness. This refers for example to the ability to successfully create offspring, and to sustain life by avoiding predators and sharing prey.

[3]There are several ways in which ecological classifications group organisms according to common functions: classification according to their habitat, to their position in the food web or to their functional feeding mechanism.

Classification by ‘habitat’

Aquatic organisms can be divided into four major groups: pelagic, benthic, neuston and fringing, according to the water body which they inhabit.[3]

Sub-categories described in the Coastal Wiki are:

- Rocky shores

- Sandy shores

- Continental shelf habitat

- Open oceans

- Deep sea habitat

- Coral reefs

- Seagrass meadows

- Mangroves

- Salt marshes

- Estuaries

Pelagic

Pelagic organisms are those that live in ocean water and are not associated with the bottom. They thus inhabit the water column and can be divided into plankton and nekton. Plankton are organisms that are suspended (they float or are weakly self-propelled) in the water and drift with it as it moves. Plankton is either passive and includes algae, bacteria and variety of animals. Plankton is usually subdivided in phytoplankton (photosynthethic organisms like algae) and zooplankton (animals), what refers to their ecological function. Plankton can also be subdivided in holoplankton and meroplankton. Holoplankton are permanent members, represented by many taxa in the sea. Meroplankton are temporary members, spending only a part of their life cycle as plankton. They include larvae of anemones, barnacles, crabs and even fish, which later in life will join the nekton or the benthos. Meroplankton are very much a feature of the sea, particularly coastal waters, as the often sedentary adult forms of coastal species use their planktonic stage for dispersal. Nekton are organisms swimming actively in the water, it includes a variety of animals, mostly fish.

Benthic

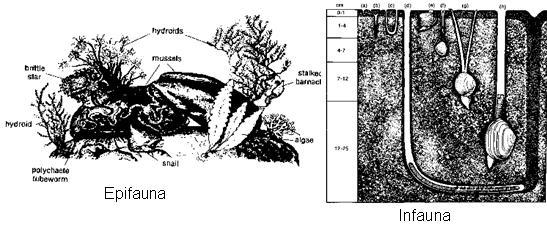

Benthos comprises organisms on the bed of the water body. Animals attached to or living on the bottom are referred to as epifauna, while those which burrow into soft sediments or live in spaces between sediment particles are described as infauna.

Attached multicellular plants and algae are referred to as macrophytes, while single-celled or filamentous algae are called as periphyton or microphytobenthos. Epiphytic algae are those which grow on macrophytes. Benthic consumers can be divided by size into macrofauna (>500 μm), meiofauna (10-500 μm) and micro-organisms (<10 μm).

Neuston

Neuston are those organisms associated with the water surface, where they are supported by surface tension. Most neuston require very still water surface and is therefore very restricted in the sea.

Fringing community

Fringing communities are floral communities that occur where the water is shallow enough for plentiful light to reach the bottom, allowing the growth of attached photosynthesisers, which may be entirely submerged or emergent into the air. Marine communities are composed mostly out of algal seaweeds. Wetlands are composed of this type of vegetation.

There are many other habitat classifications, for example the EUNIS Habitat types classification.[4]. This is a comprehensive pan-European system to facilitate the harmonized description and collection of data across Europe through the use of criteria for habitat identification; it covers all types of habitats from natural to artificial, from terrestrial to freshwater and marine.

An example of the EUNIS habitat classification: marine habitats at level 1 is the following:

- Littoral rock and other hard substrata

- Littoral sediment

- Infralittoral rock and other hard substrata

- Circalittoral rock and other hard substrata

- Sublittoral sediment

- Deep-sea bed

- Pelagic water column

- Ice-associated marine habitats

Classification by position in the food web

[5]It is very difficult to make generalizations about the trophic relationships in coastal marine systems, because the ecological habitats are so diverse. A simplified description of a food web: the phytoplankton are the primary producers and are eaten by the zooplankton (smallest floating animals). The zooplankton are eaten by small fish (sardines, herring) and small fish are eaten by larger fish. At the top of the marine food web are the large predators (tuna, seals, sea-birds and some species of whales).

Phytoplankton, small zooplankton and large zooplankton, larger animals and top predators all interact in a marine food web. Each species eats and is eaten by several other species at different trophic levels. The microbial loop is an important component of the marine food web.

The interactions in a food web are far more complex than the interactions in a food chain. Furthermore, the branching structure of food webs leads to fewer top predators compared with the numbers of top predators in a food chain.

Classification by functional feeding mechanism

Coastal benthos functional groups[3]

There is a classification with several functional groups for marine and coastal systems:

- grazer-scrapers feed upon attached algae

- scavengers eat coarse particulate organic matter (detritus retained by a 1 mm sieve)

- collectors eat fine particulate organic matter (detritus passing through a 1 mm sieve but retained by 0.45 mm sieve)

- suspension or filter feeders remove particles from the water column

- deposit feeders pick particles from the ocean bed

- predators consume other living animals

- parasites derive their food from a living organism of another species (host), they usually live in or on the body of the host.

In practice this distinction is very imprecise but useful as long as it is understood that they should not be too rigidly applied. The shelf bottom is occupied by diverse groups of benthic organisms that vary with changes in the bathymetry and sediment cover of the sea bed. For example gravel and coarse sand bottoms are mostly populated by filter feeders and fine sand bottoms are predominantly composed of deposit feeders. Muddy substrates are almost exclusively inhabited by deposit and detritus feeders.

Pelagic functional groups

In pelagic communities the classification based on feeding mechanism is less successful because consumers are opportunistic and will eat anything that is the correct size for their mouthparts.[3]

Nekton are almost exclusively predators. The smaller species like the zooplankton are both predators and grazers. Plankton are therefore also classified by size, although there is again an overlap as many species will change to a larger size class as they grow older.

Related articles

References

- ↑ Reiss, J., Bridle, J.R., Montoya, J.M. and Woodward, G. 2009. Emerging horizons in biodiversity and ecosystem functioning research. Trends Ecol. Evol., 24: 505-514

- ↑ Thorne-Miller Boyce (1999) The living ocean: understanding and protecting marine biodiversity. United States of America 213p

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Dobson M. and Frid C. (1998). Ecology of aquatic systems. Addison Wesley Longman Limited: Edingburgh, (England). p. 222 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Dobson" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ http://eunis.eea.europa.eu/habitats.jsp

- ↑ http://oceanworld.tamu.edu

- ↑ From "Fishing down marine food webs' as an integrative concept" by Daniel Pauly (University of British Columbia, Canada), Proceedings of the EXPO'98 Conference on Ocean Food Webs and Economic Productivity, online at the Community Research and Development Information Page

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|