Difference between revisions of "Monitoring changes in North Atlantic plankton communities"

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

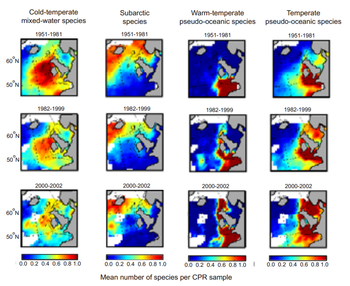

[[Image:CPR.graph.PNG|thumb|350px|right|Changes in the mean number of copepod species from 1951-2002, showing northward extension of warm water species and northward retreat of cold water species. Recalculated after Beaugrand et al., 2002.]] | [[Image:CPR.graph.PNG|thumb|350px|right|Changes in the mean number of copepod species from 1951-2002, showing northward extension of warm water species and northward retreat of cold water species. Recalculated after Beaugrand et al., 2002.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Long-term plankton monitoring and non-indigenous species== | ||

| + | The introduction of non-indigenous marine plankton species can have a considerable ecological and economic effect on regional systems. For example the introduction of the ‘comb jelly’ (''Mnemiopsis leidyi'') to the Black Sea is known to have had dramatic consequences on the food web. The main pathway for invasive species introduction is via ship ballast waters. There has been increasing concern about the apparent increase in species introductions worldwide, but their presence can go unnoticed until they reach nuisance status. As a consequence there are few case-histories providing information on their initial appearance and their spatio-temporal patterns. Since the 1980’s phytoplankton biomass has increased in the North Sea. How much of this increase can be attributed to the introduced phytoplankton species ''Coscinodiscus wailesii'' is yet to be determined. There is however, already strong evidence to suggest that under certain conditions ''C. wailesii'' can displace indigenous plankton species. As many native phytoplankton feeders find the species unpalatable, its dominance can have detrimental effect on the food web. Such shifts in ecology of the North Sea need to be monitored by sustained long-term observations. The case of ''C. wailesii'' is the first of its kind to show the spatial evolution of an invasive phytoplankton species over a decadal period and highlights the need for continuous monitoring to assess the effectiveness of any management strategy put in place to limit invasions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science (SAHFOS) [http://www.sahfos.org www.sahfos.org] | ||

Revision as of 09:16, 5 July 2012

Contents

Background

The North Atlantic is the largest oceanic water mass associated with Europe and thus a key area for the EUR-OCEANS network. The outcome of many nationally-funded research programmes over the last decade had been the realisation that human impacts (e.g. climate change, species introductions) apply across the North Atlantic basin, thus requiring the cohesive and coordinated research promoted by EUR-OCEANS. This Fact Sheet introduces some of the conclusions regarding possible human induced changes in the North East Atlantic planktonic communities over the last 50 years. These conclusions are based on long-term plankton records which are valuable for documenting ecosystem changes, for helping to separate natural and anthropogenic changes, and for generating and analyzing testable hypotheses. Over the last decade, interest in long-term plankton sampling has increased. However, long timeseries are still uncommon. The purpose of long-term monitoring is to establish a baseline for the various components of the ecosystem, and how they interact. Information can be used to:

- distinguish between the effects of human activities and natural variability

- define baselines and estimate the recovery time of the system after human or environmental perturbations

- develop hypotheses about causal relationships which can then be investigated

- verify and validate models used to predict changes in marine ecosystems on the basis of climate scenarios, and

- evaluate management actions.

Climate change

Long-term variations in plankton abundance in the North Atlantic ecosystem have been investigated by the Continuous Plankton Recorder (CPR) survey since 1946 as well as at several fixed coastal monitoring stations.

Studies show that key mechanisms link environmental forcing and plankton response i.e. timing and intensity of the spring phytoplankton bloom resulting from changes in stratification levels, changes in temperature, and, in the case of the copepod Calanus finmarchicus, advection of the population into the North Sea at the end of the winter season. The NE Atlantic has warmed 2-3°C over the last 50 years. This has resulted in a northwards shift (of approximately 1000km) in warm water plankton communities. There has also been a decrease in the key copepod Calanus finmarchicus and an increase Calanus helgolandicus. Such a shift could impact on the whole ecosystem, for example larval/juvenile cod feed on C. finmarchicus, its replacement by C. helgolandicus may therefore have a detrimental effect on their overall viability because both species are abundant at different times of the year. Such changes may have exacerbated the impact of over-fishing in reducing recruitment of North Sea cod since the mid-1980s.

Long-term plankton monitoring and non-indigenous species

The introduction of non-indigenous marine plankton species can have a considerable ecological and economic effect on regional systems. For example the introduction of the ‘comb jelly’ (Mnemiopsis leidyi) to the Black Sea is known to have had dramatic consequences on the food web. The main pathway for invasive species introduction is via ship ballast waters. There has been increasing concern about the apparent increase in species introductions worldwide, but their presence can go unnoticed until they reach nuisance status. As a consequence there are few case-histories providing information on their initial appearance and their spatio-temporal patterns. Since the 1980’s phytoplankton biomass has increased in the North Sea. How much of this increase can be attributed to the introduced phytoplankton species Coscinodiscus wailesii is yet to be determined. There is however, already strong evidence to suggest that under certain conditions C. wailesii can displace indigenous plankton species. As many native phytoplankton feeders find the species unpalatable, its dominance can have detrimental effect on the food web. Such shifts in ecology of the North Sea need to be monitored by sustained long-term observations. The case of C. wailesii is the first of its kind to show the spatial evolution of an invasive phytoplankton species over a decadal period and highlights the need for continuous monitoring to assess the effectiveness of any management strategy put in place to limit invasions.

See also

Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science (SAHFOS) www.sahfos.org