Shore nourishment

Background and general considerations: Nourishment can be divided into three types -backshore nourishment, beach nourishment and shoreface nourishment. Nourishment as part of a shoreline management project, which combines structures and initial nourishment, also referred to as Beach Fill, will not be discussed here; however, the general considerations regarding nourishment, as discussed in the following, also apply for beach fill combined with structures.

Contents

What is nourishment?

Nourishment can be regarded as a very natural way of combating coastal erosion and shore erosion as it artificially replaces a deficit in the sediment budget over a certain stretch with a corresponding volume of sand. However, as the cause of the erosion is not eliminated, erosion will continue in the nourished sand. It is thus inherent in the nourishment concept that the nourished sand is gradually sacrificed. This means that nourishment as a stand-alone method normally requires a long-term maintenance effort. In general, nourishment is only suited for major sections of shoreline; otherwise the loss of sand to neighbouring sections will be too large. Regular nourishment requires a permanent well-functioning organisation, which makes nourishment as a stand-alone solution unsuitable for privately owned coastlines.

The success of a nourishment scheme depends very much on the grain size of the nourished sand, the so-called borrow material, relative to the grain size of the native sand. As described in Section 6.3, the characteristics of the sand determine the overall shape of the coastal profile expressed in the equilibrium profile concept. Furthermore, in nature the hydrodynamic processes tend to sort the sediments in the profile so that the grain size decreases with increasing water depth.

Equilibrium conditions

When borrow sand is placed in a coastal profile, neither the profile nor the grain size distribution will match the equilibrium conditions. Nature will attempt to re-establish a new equilibrium profile so changes will always occur in the nourished profile. There will also be changes caused by the continued long-term erosion trend and the profile response to individual events. This means that in practice it is neither possible to perform a short-term nor a long-term stable nourishment at an eroding coast. It is inherently unstable on eroding shorelines. These are the basic realities, which the public, the politicians and those who fund the projects, find it hard to accept. On the other hand, as environmental concerns and requirements for sustainability are gaining in importance, nourishment has gradually increased its share of shoreline management schemes over the last decades.

Grain size

As mentioned above, the performance of a nourishment scheme very much depends on the grain size of the borrow material relative to the grain size of the native material, see the discussion of equilibrium profiles in Section 6.3 and Fig 6.5.

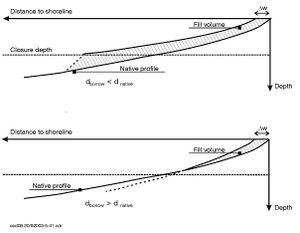

If the borrow sand is finer than the native sand, it will tend to form a flatter profile than the natural one. The equilibrium reshaping of the nourished sand will reach out to the closure depth. If the objective of the nourishment is to obtain a wider beach, this will require very large volumes of sand, as illustrated in the upper part of Fig 12.28.

28. Equilibrium conditions for nourished beaches required to obtain an additional beach width of w with borrow sand, which is finer and coarser than the native sand (upper and lower, respectively).

It is evident that the volume of sand needed to obtain a certain beach width increases drastically with the decreasing grain size of the nourished sand. Most coastal authorities realise this and some of them have introduced special bonuses for their nourishment contractors when they provide coarse sand.

It is evident from this figure that if borrow sand with a larger grain size than that of the native sand is nourished into a coastal profile, it will tend to form a steeper profile than the natural profile. This means that a wider beach will tend to be formed, see Fig 12.28 lower part.

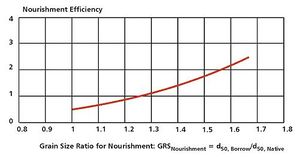

Furthermore, coarser sand will be more stable in terms of longshore loss. This nourishment efficiency of the nourished sand has been studied by the Danish Coastal Authority on basis of many years of nourishment along the Danish North Sea Coast ([1]). The nourishment efficiency is defined as the ratio between the erosion rate for the natural sand (theoretical) and that of the nourished sand. The nourishment efficiency has been analysed as function of the ratio between the mean grain size of the borrow sand and that of the native sand:

GSRNourishment = d50, Borrow/d50, Native .

The analysis covers effects of cross shore as well as longshore effects. The results are expressed as a relation between the nourishment efficiency versus the grain size ratio

GSRNourishment.

29. Relation between Nourishment Efficiency and the Grain Size Ratio for Nourishment (Vestkysten 2000)

It is evident from the relation shown in Fig 12.29 that the Nourishment Efficiency increases considerably with increasing Grain Size Ratio for Nourishment.

Steepness of profile

Areas, which for a long time have been protected by hard coastal protection structures, have often developed steepened coastal profiles. Such areas are very far from their cross-shore equilibrium form. If nourishment is introduced in such areas it will require huge volumes of sand to restore the profile to the equilibrium profile, which is required to release the pressure on the coastal structures. In such cases, it is very important to find borrow sand, which is coarser than the native sand.

Methods, functional characteristics and applicability

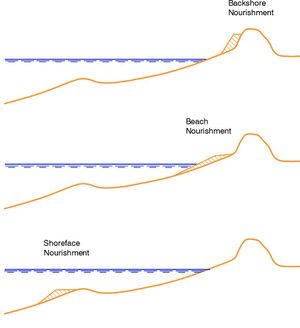

The three different nourishment methods will be discussed briefly in the following.

30. Principles in backshore nourishment, beach nourishment and shoreface nourishment.

Backshore nourishment

Backshore nourishment is the strengthening of the upper part of the beach by placing nourishment on the backshore or at the foot of the dunes. The main objective of backshore nourishment is to strengthen the backshore/dune against erosion and breaching during extreme events. The material is stockpiled in front of the dunes and acts as a buffer, which is sacrificed during extreme events. This kind of nourishment works more by volume than by trying to restore the natural wide beach. The loss is normally large during extreme events, whereby steep scarps are formed. Backshore nourishment can be characterised as a kind of emergency measure against dune setback/breach; it cannot, therefore, be characterised as a sustainable way of performing nourishment and it does not normally look very natural.

Backshore nourishment can be performed by hydraulic pumping sand through pipes discharging at the foot of the dunes and later adjusted using a bulldozer. The sand source can be either an offshore supply via a cross-profile pipeline, floating or buried, or it can be supplied along the shore from, for example, a sand bypassing plant. The sand can also be supplied via land transport by dumpers.

Beach nourishment

Beach nourishment is the supply of sand to the shore to increase the recreational value and/or to secure the beach against shore erosion by feeding sand on the beach. It is not a coastal protection measure, as the beach will normally be flooded during extreme events, but it will support possible coastal protection measures. When performing beach nourishment, the borrow sand must be similar to the native sand to adjust smoothly to the natural profile. It may be an advantage to use slightly coarser sand than the natural beach sand, as this will enhance the stability of the resulting slightly steeper profile. Finer sand will very quickly be transferred to deeper water and will thus not contribute directly to a wider beach. However, the fine sand will help building up the outer part of the profile.

Shoreface nourishment

Shoreface nourishment is the supply of sand to the outer part of the coastal profile, typically on the seaside of the bar. It will strengthen the coastal profile and add sediment to the littoral budget in general. This type of nourishment is used in areas where coastal protection measures have steepened the coastal profile or in areas with a long-term sediment deficit. Shoreface nourishment is sometimes used with beach nourishment in order to strengthen the entire coastal profile. It is recommended for obtaining a nourished profile close to the equilibrium profile. Stand-alone shoreface nourishment acts only indirectly as a shore protection measure through slightly decreased wave exposure and as a shore restoration measure with considerable delay and little efficiency.

Shoreface nourishment is often performed using split barges. The unloading is fast and the unit price therefore low. Shoreface nourishment can profitably be used in connection with large beach nourishment schemes, in which borrow material, which does not fulfil the requirements for beach nourishment, can be used in the outer part of the profile where it naturally belongs.

31. Nourishment methods in practice by the Danish Coastal Authority. Beach nourishment by pipe discharge on the beach and over the bow pumping and shoreface nourishment by split barge.

Beach Scraping

- Definition

Beach scraping is recovering material from the berm at the foreshore and placing it on the backshore at the foot of the dunes or the cliff.

Method: A beach berm consisting of coarse sand or gravel is sometimes formed during relatively mild summer wave conditions, which tend to transport seabed material towards the beach. Beach scraping is normally performed using front loaders.

Functional characteristics: The purpose of beach scraping is to strengthen the upper part of the beach profile and the foot of the cliff. The material is placed in a position that reduces the erosion occurring during storm surge conditions.

Applicability: This method can be used for beaches, which are mainly exposed to seasonal erosion, whereas it is probably not feasible for locations, which are exposed to long-term erosion. One disadvantage of the method is that the material used for strengthening the upper part of the beach profile is taken from the lower part of the same profile, which means that the method only contributes insignificantly to the overall stability of the beach profile. Another issue is that equipment operated during late summer may disturb recreational activities.

Beach De-watering or Beach Drain

- Definition

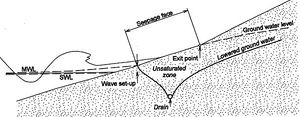

A beach de-watering system or beach drain, is a shore protection system working on the basis of a drain in the beach. The drain runs parallel to the shoreline in the wave up-rush zone. The beach drain increases the level of the beach near the installation line, thus also increasing the width of the beach. The beach drain method is patented world wide by GEO, Denmark.

Method: The drain consists of a permeable plastic pipe installed 1.0 to 2.0 m below the beach surface in the wave up-rush zone. If there is a significant tide, the drain must be installed close to the MHWS line, i.e. near the shoreline. The drain is connected to a pumping well from which the drain water is pumped, either into a lagoon or back into the sea. The only visible part of the drain installation is the pumping well and a small control house.

32. Principle of beach drain function

Functional characteristics:

The conditions influencing the function of the drain are summarised in the following:

- The site must have a sandy beach. The beach sediments must be sand, preferably with a mean grain diameter in the range of

0.1 mm < d50 < 1.0 mm and preferably sorted to well sorted (Cu = d60/d10 < 3.5).

These conditions give the permeability that provides optimal functionality of the beach drain.

- The beach drain works by locally lowering the groundwater table in the uprush zone, which decreases the strength of the down-rush as a higher fraction of the water percolates into the beach. Furthermore, the physical strength properties of the beach sand is increased remarkably by the lowering of the water table in the wave up-rush zone thereby making the beach more resistant against erosion. The groundwater table in the beach is a function of several factors, the most important of which are: a) the groundwater table conditions in the coast and the hinterland, b) the groundwater table caused by tide and storm surge, and c) the groundwater table caused by waves.

- A high groundwater table in the coast and the hinterland influences beach stability and beach formation. The hinterland-based groundwater table saturates a large portion of the beach, causing groundwater seepage through the foreshore. This seepage tends to destabilise (fluidise) the foreshore. The beach drain locally lowers the groundwater table to the level of the drain and counteracts the destabilisation.

- The beach drain works well at locations with relatively high tide because the tide generates an elevated groundwater table in the beach, which can be lowered considerably by the drain. It can therefore be stated that the presence of high tide at a location enhances the functionality of the drain.

- The presence of high storm surges will affect the functionality of the drain by moving the uprush zone landwards away from the drain. The function of the drain during high surge conditions will mainly be indirect; the previously accumulated sand will act as a buffer for the erosion during the storm. When the storm surge falls, the elevated groundwater-level in the beach will increase beach erosion if there is no beach drain to prevent it.

- Waves on a beach increase the height of the local groundwater table in the beach, partly due to the wave run-up on the foreshore and partly due to the locally elevated water-level in the uprush zone called wave set-up. Once again, the beach drain counteracts this.

- The beach drain requires some wave activity on the beach as the drain works by manipulating the downrush conditions on the foreshore. Too small and too high waves make the beach drain inefficient. It works best on moderately exposed coasts.

- As the beach drain system functions only on the foreshore in the uprush zone, it does not directly protect the entire active profile against erosion. Consequently, it is best suited at locations with seasonal beach fluctuations or where the objective is a wider beach at an otherwise stable section of the shoreline. For locations that experience on-going recession of the entire active coastal profile, the beach drain is probably only suitable combined with other measures. The long-term capability of the beach drain under such circumstances remains to be tested.

Applicability:

The beach drain is best suited for the management of beaches with the following characteristics:

- Sandy beaches

- Moderately exposed to waves

- Exposed to tide

- Suffering from high groundwater table on the coast and on the beach

- Exposed to seasonal fluctuations of the shoreline

- Exposed to minor long-term beach erosion

- Locations with a narrow beach, where a wider beach is desired

The beach drain is, however, not recommended as a primary shore or coastal protection at locations with the following characteristics:

- Severely exposed locations

- Protected locations

- Locations exposed to severe long-term shore erosion and coast erosion