Fisheries in De Panne

Contents

Overview and Background

The Belgian coast is 67 km long and is entirely bordering the province of West-Flanders (region of Flanders, Belgium). The Belgian part of the North Sea is 3,457 km2 (0.5% of the North Sea area), of which more than 1/3 or 1,430 km² are territorial sea within 12 nautical miles distance of the coastline. Belgium currently has 10 coastal municipalities and 4 coastal ports (Nieuwpoort, Oostende, Zeebrugge and Blankenberge), and besides the fish auctions located in Oostende, Zeebrugge and Nieuwpoort where fish is sold according to legal procedures, there are no other dispersed landing points. Although historically the port and auction of Oostende was by far the most important, today the auctions of Zeebrugge (53%) and Oostende (45%) receive the largest share of the landings of Belgian fisheries in Belgian ports.

Belgium has a minor role in the European fisheries context with 0.35% of the total EU production of fish. In 2012, the Belgian commercial sea fishing fleet counted 86 ships, with a total engine capacity of 49,135 kW and gross tonnage of 15,326 GT [1]. 45 vessels are part of the Small Fleet Segment (max 221 kW engine power) of which 2 use passive gear. The remaining 41 vessels belong to the Large Fleet Segment and have an engine power between 221 kW and a maximum of 1,200 kW. This fleet segment represents approximately 80% of the engine power capacity and 77% of the GT of the fleet. While a smaller number use trammel nets (passive gear) and otter trawl, the largest share of the Large Fleet Segment are beam trawl vessels (≥662 kW). The Belgian fleet is highly specialized: more than 68% of the effort(days at sea) and 77% of total landings are achieved by beam trawlers(2010)focusing primarily on flatfish species such as plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and sole (Solea solea). The results of the reconstruction of the Belgian fleet dynamics since 1830 are presented in Lescrauwaet et al. 2013[2].

The number of days at sea per vessel is fixed at a maximum of 265 per year and in 2011 the entire fleet realized a fishing effort of 15,855 days at sea. In 2011, the Belgian fleet landed a total of 20,138t, of which 16,905t were landed in Belgian ports. Plaice is the most important species in terms of landed weight. The landings of 2011 represented a value of €76.3 million, 14% of which was marketed in foreign ports. Sole generates 47% of the current total value of fisheries in Belgium. The Belgian sea fisheries represent 0.04% of the national Gross Domestic Product [3]. The main fishing grounds in terms of volume of landings in 2010 were in descending order: North Sea South (IVc), Eastern English Channel (VIId), North Sea Central (IVb), Southeast Ireland/Celtic Sea (VIIg) Bristol Channel (VIIf) and Irish Sea (VIIa).

In terms of direct employment, 439 fishers are registered of which approximately 350 are of Belgian nationality. Direct employment in fisheries represent approximately 0.5% of the total employment in the Belgian coastal zone. Another 1040 persons work in the fish processing industry and another 5000 persons in associated trade and services [1]. A historical overview of Belgian sea fisheries is available from [4] and [2].

The Belgian sea fishery sector is rather small compared to that of neighbouring countries in the North Sea and has been gradually losing importance since the Second World War. It is also gradually losing importance relative to the booming tourism industry in the Belgian coastal zone. However fisheries can be an added value to the tourism experience at the coast by developing fisheries-related tourism activities [5].

Port description

De Panne (Geographical coordinates: 51°06'N 2°36'E) is the westernmost Belgian coastal town, which means it shares a border with France. It has a population of almost 10.800 people. The history of De Panne is closely linked with that of Adinkerke, nowadays a small village, situated about 3 kilometres from the sea, that belongs to the municipality of De Panne. The situation used to be reversed however: during the late 18th century, De Panne was part of the larger parish and municipality of Adinkerke [6]. Yet, because of growing importance of coastal tourism from the late 19th century on, De Panne eventually transformed into a larger town than Adinkerke and became independent in 1911 [7]. Originally though, De Panne was primary a fishing place. It was only founded in 1783, during the time the Austrian branch of the Habsburg monarchy ruled the Southern Netherlands. Emperor Joseph II wanted to stimulate the inshore fisheries and therefore agreed with the proposition of six dignitaries from Veurne to erect a small fishing settlement in the dunes between Adinkerke and Koksijde. Two years after its foundation, the village of De Panne (originally named ‘Josephdorp’ - after Joseph II - and ‘Kerckepanne’) already counted 26 houses [6][8][9]. The fishers used specific vessels, named ‘pannepotten’ or ‘panneschuiten’, which moored on the beach [10].

|

Fig. 1. Typical fishermen’s houses in the settlement of ‘Duinhoek’ in De Panne. Most of these fishers were farmers as well. The houses were built right behind the dunes, where they were sheltered from the wind and hedges and branches protected the fields from the swirling sand [9] (Source: Bauwen, L.; Andries, J., 2002). |

|

The fisheries - and especially the herring fisheries - in De Panne flourished from the middle of the 19th century on, and the fishing community steadily grew [6]. Around the turn of the century, a number of shipyards were active in De Panne, while several small fish smoke houses were also present in the village [11]. An important figure in this thriving evolution was Pierre Bortier (1805-1879), a wealthy landowner and philanthropist, who strongly believed that agriculture and fisheries were the crucial basis for a prosperous society. Bortier was closely involved in the fishery life of De Panne and encouraged the fishermen to take ownership of their very own fishing vessels, which was one of the reasons for the prosperous situation of the fisheries sector in De Panne during the second half of the 19th century [11][7]. With 2050 inhabitants and 88 fishing vessels in 1903, De Panne was the second most important Belgian fishers community (after Ostend) at the time [6][12]. The lack of an own harbour however, eventually led to the decline of the fishery industry in De Panne. Although over the years, several plans were made for the construction of an own harbour for the fishing fleet of De Panne, none of these projects actually succeeded. After the First World War, more and more fishers left De Panne for Nieuwpoort and Ostend and soon after the Second World War, all professional fishery activity in De Panne ceased to exist [6].

Fig. 3. The landing and counting of the herring in De Panne in the 1930s. The fish auction was originally held in the Veurnestraat in De Panne, but relocated to the seawall after the First World War (as pictured above)(Source: Devent, 1989).

Fishing Fleet

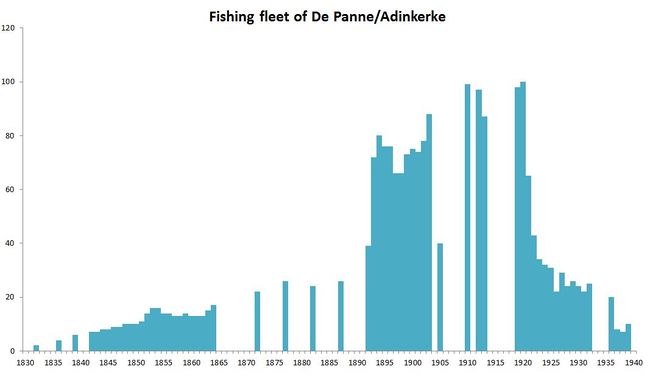

As shown on graph 1, the fleet of Adinkerke and De Panne gradually grew over the course of the 19th century and eventually increased substantially around the turn of the century. Because of the modernization and increase in scale of the fisheries sectors after World War I however, the fisheries sector soon relocated to coastal towns with harbours. Since De Panne never got its own harbour, it became less important as a fishing village, and the size of the fleet subsequently rapidly decreased [6].

- Graph 1: Fishing fleet in De Panne/Adinkerke ((Source: 1832-1841: (1866). Rapport de la Commission chargée de faire une enquête sur la situation de la pêche maritime en Belgique. Séance du 17 mai 1866. Chambre des Représentants: Bruxelles. XLII, 75 pp.; 1842-1864: Enquete sur la situation de la peche maritime en belgique instituee par arrete du 20 avril 1865, 1872-1903: ICES Fisheries Statistics = Bulletin Statistique des Pêches Maritimes, 1905: De Zuttere (1909). Enquête sur la pêche maritime en Belgique, 1910: Von Schoen, F. (1912). La pêche maritime de la Belgique, 1928: Officieele lijst der visschersvaartuigen).

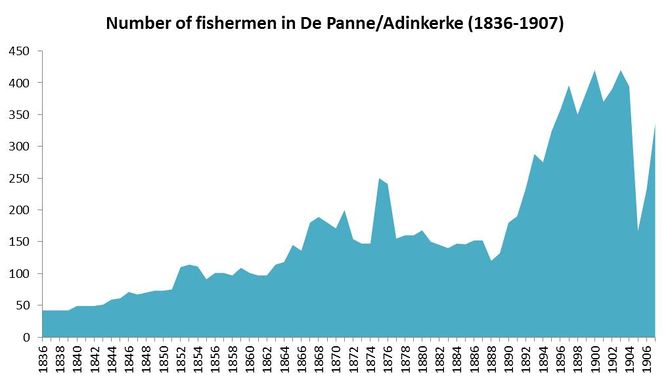

Because of the prosperous situation of the fisheries sector in De Panne and Adinkerke during the second half of the 19th century, lots of people were employed in this industry. Graph 2 illustrates the number of fishermen from 1936 until 1907. The number especially peaked around the turn of the century, parallel to the development of the fishing fleet of De Panne and Adinkerke. In 1900, no less than 420 fishermen were active in De Panne and Adinkerke [12].

- Graph 2: Number of fishermen in De Panne/Adinkerke (1836-1909)(Source: De Zuttere, 1909).

Fish shops and restaurants

De Panne has several fish shops, of which an overview can be found here and here.

‘Hostellerie Le Fox’, a restaurant with two Michelin stars, is located near the sea wall of De Panne. The chef, Stéphane Buyens, is a passionate advocate of using local ingredients in his dishes. For his fish meals, he resolutely chooses fresh fish from the North Sea. This includes such species as plaice, cod, sole and shrimp, which he deems ‘the caviar of the North Sea’ [13]. Several other restaurants in the neighbourhood, such as ‘Le Flore’, ‘Tram 57’, ‘La Coupole’ and ‘Au Filet de Sole’, also value working with local products and fresh North Sea fish.

Quality labels

The Flemish brown shrimp is a typical fisheries product in Belgium. In 2006 the Purus label was introduced by a cooperation of ship owners, the cooperative Flemish fisheries organization (Cooperative Vlaamse Visserij Vereniging CVBA) to promote the Flemish unpeeled brown shrimps. The brown shrimps are caught by Belgian fishermen, the fishermen fish no longer than 24 hours and the shrimps are cooked in old Flemish manner (in sea water with salt), there are no additives, preservatives added. This all results in high quality taste. The Purus label also promotes sustainable fishing techniques.

Since 2011, the Flemish Shellfish- and fish cooperation (VSVC) supply, via an exclusive quality label, ‘North Sea Life’, life brown shrimps and swimming crabs to restaurants and wholesalers. Life shrimps allows chefs to determine how they will prepare the shrimps. Life product forms the base of creative and gastronomic possibilities. The same is true for life swimming crabs. In 2013 a minimum of 200 kilo life brown shrimps were landed each day. Prices for life shrimps are on average 30 percent higher than shrimps cooked on board of the shrimp vessel [14].

Organisations

In Belgium, the FLAG, also called the ‘local group’, ‘Plaatselijke Groep Belgisch Zeevisserijgebied’, is a partnership between socio-economic stakeholders in the fisheries sector, NGOs and public authorities that play a crucial role in the implementation of the proposed development strategy. The lead partner of the Belgian FLAG is the Province of West Flanders. The main focus of the FLAG strategy is to add value to local fisheries products and increase local consumption. Belgian landings represent only 10% of fisheries products consumed in Belgium, leaving the remaining 90% to be met by imports. Therefore there is a considerable potential for discovering and developing local markets. It will also support diversification, innovation, the involvement of women and efforts to promote the sustainable management of the marine environment[15].

- Fig. 6. Belgian FLAG area: West Flanders

In 1894, a first attempt was made to open a fisheries school in De Panne, but it was unfortunately a short-lived endeavor. However, in 1903, the reverend father Vanneste resurrected the idea and founded a fisheries school, modelled after similar institutes in other Belgian coastal towns. The fisheries school in De Panne was one of the most attended, with around 80 or 90 students [16]. The school closed its doors in 1935 [17].

In De Panne, the local history and heritage club ‘De Panneboot P1’ was founded in 1993. Its primary objective is the preservation, maintenance and promotion of the maritime heritage that laid the foundation for the development of this coastal town. The most important activity of this club is the maintenance of the fishing vessel ‘De Pannevisser P1’, but its members also collect all kinds of data about the history of fisheries in De Panne and the West Coast [18]. More recently, this organisation was also the driving force behind the foundation of the ‘Retrohuis De Viswinkel’ (‘Retrohouse The Fish Shop’) [19] (see also ‘Fisheries related activities’).

Although De Panne has known a long maritime tradition, nowadays only few traces are left of its history as a fishing village [20]:

- In De Panne you can visit the provincial visitors centre ‘De Nachtegaal’, which is located in the centre of the nature reserve ‘Duinen en Bossen De Panne’ (‘Dunes and woods De Panne’). ‘De Nachtegaal’ wants to provide visitors information on coastal environments and also discusses the history of the human occupation of the coastal region. As such, the story of the habitation of the dunes by fishermen is also briefly addressed [21].

- In the ‘Retrohuis De Viswinkel’ (‘Retrohouse The Fish Shop’), visitors nostalgically look back at the old fish shop of the late G. Vanzeebrouck, which also included an ice shop and a small artisan fish smokehouse. The exhibition sheds light on the history of local fisheries and tells the story of the fishing village that De Panne used to be. The house contains several models of fishing vessels, pictures and all kinds of objects related with fishing. The Retrohouse is an initiative of the local history and heritage club ‘De Panneboot P1’ (Retrohuis De Viswinkel, Site Gemeente De Panne).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Roegiers, B.; Platteau, J.; Van Bogaert, T.; Van Gijseghem, D.; Bekaert, K.; De Bruyne, S.; Delbare, D.; Depestele, J.; Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Moreau, K.; Polet, H.; Robbens, J.; Vandamme, S.; Van Hoey, G.; Verschueren, B. (2013). VIRA Visserijrapport 2012 Departement Landbouw en Visserij: Brussel. 98 pp.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lescrauwaet, A.-K. (2013). Belgian fisheries: ten decades, seven seas, forty species: Historical time-series to reconstruct landings, catches, fleet and fishing areas from 1900. PhD Thesis. Ghent University (UGent): Gent. xiii, 242 pp.

- ↑ Anon. (2008). Strategische Milieubeoordeling van het Nationaal Operationeel Plan voor de Belgische visserijsector, 2007 - 2013. ILVO Visserij: Oostende. 103 pp.

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Debergh, H.; Vincx, M.; Mees, J. (2010). Fishing in the past: Historical data on sea fisheries landings in Belgium. Mar. Policy 34(6): 1279-1289. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.05.006

- ↑ Anon. (2011). Europees Visserijfonds (EVF). AS 4: ontwikkelingsstrategie voor het Belgisch kustgebied. Europees Visserijfonds: (s.l.). 33 pp.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Gyselinck, N.; Lanszweert, W.; Steevens, I.; Wolny, M. (2013). Kust- en zeevisserij, in: Steevens, I. et al. (Ed.) (2013). Zeevisserij aan de Vlaamse kust. pp. 114-165.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Geschiedenis van De Panne en Adinkerke in een notendop, Site Gemeente De Panne.

- ↑ Bauwens, J. (2012). Ooit droomden Pannese vissers van een 'eigen' haventje!, in: Berquin, H. (Ed.) (2012). In het zand geschreven. De duinen van de Westhoek: een geschiedenis. pp. 193-229.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Devent, G. (1989). De Vlaamse zeevisserij. Marc Van de Wiele: Brugge. ISBN 90-6966-061-X. 208 pp.

- ↑ Desnerck, G.; Desnerck, R. (1976). Vlaamse visserij en vissersvaartuigen: 2. De vaartuigen. Gaston Desnerck: Oostduinkerke. 543 pp.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Desnerck, G.; Desnerck, R. (1974). Vlaamse visserij en vissersvaartuigen: 1. De havens. Gaston Desnerck: Oostduinkerke. 256 pp.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 De Zuttere, C. (1909). Enquête sur la pêche maritime en Belgique: introduction, recencement de la pêche maritime. Lebègue & cie: Bruxelles. 634 pp

- ↑ Interview Stéphane Buyens, Site Het Lekkere Westen.

- ↑ Press release ILVO, 29/05/2013

- ↑ FLAG factsheet - Belgium - West Flanders

- ↑ Beun, A.-S.; Lanszweert, W.; Leerman, F.; Steevens, I. (2013). Kinderen in de visserij en het onderwijsaanbod, in: Steevens, I. et al. (Ed.) (2013). Zeevisserij aan de Vlaamse kust. pp. 68-91.

- ↑ Voorgeschiedenis, Site Visserijschool John Bauwens.

- ↑ Heemkundige vereniging ‘De Panneboot P1’, Site De Bliedemaker.

- ↑ Retrohuis De Viswinkel, Site Gemeente De Panne.

- ↑ Provincie West-Vlaanderen (2008). Studieopdracht Provincie West-Vlaanderen: 'Maritiem erfgoed aan de kust': eindrapport. Contactforum voor Erfgoedverenigingen: Antwerpen. 51 pp.

- ↑ Provinciaal Bezoekerscentrum De Nachtegaal, Site Gemeente De Panne.