Difference between revisions of "Fisheries in Heist"

(→Fish shops and restaurants) |

|||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

::::::Fig. 4. and 5. The fish shop ‘Depaepe’, then and now. (Source: [http://www.vishandeldepaepe.be/ Vishandel Depaepe]) | ::::::Fig. 4. and 5. The fish shop ‘Depaepe’, then and now. (Source: [http://www.vishandeldepaepe.be/ Vishandel Depaepe]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===<span style="color:#3a75c4; Font-size: 130%">'''<small>Quality labels</small>'''</span>=== | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | The Flemish brown shrimp is a typical fisheries product in Belgium. In 2006 the Purus label was introduced by a cooperation of ship owners, the cooperative Flemish fisheries organization (Cooperative Vlaamse Visserij Vereniging CVBA) to promote the Flemish unpeeled brown shrimps. The brown shrimps are caught by Belgian fishermen, the fishermen fish no longer than 24 hours and the shrimps are cooked in old Flemish manner (in sea water with salt), there are no additives, preservatives added. This all results in high quality taste. The Purus label also promotes sustainable fishing techniques. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since 2011, the Flemish Shellfish- and fish cooperation (VSVC) supply, via an exclusive quality label, ‘[http://www.northsealife.be/ North Sea Life]’, life brown shrimps and swimming crabs to restaurants and wholesalers. Life shrimps allows chefs to determine how they will prepare the shrimps. Life product forms the base of creative and gastronomic possibilities. The same is true for life swimming crabs. In 2013 a minimum of 200 kilo life brown shrimps were landed each day. Prices for life shrimps are on average 30 percent higher than shrimps cooked on board of the shrimp vessel<ref>http://www.ilvo.vlaanderen.be/NL/Persenmedia/Allemedia/tabid/6294/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/1105/language/nl-NL/ILVO-ziet-in-rauwe-garnaal-meer-dan-lucratieve-niche.aspx#.UyBv6vldVSL</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <gallery> | ||

| + | File:Purus.jpg | ||

| + | File:North_Sea_Life.jpg | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===<span style="color:#3a75c4; Font-size: 130%">'''<small>Organisations</small>'''</span>=== | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | In Belgium, the FLAG, also called the ‘local group’, ‘Plaatselijke Groep Belgisch Zeevisserijgebied’, is a partnership between socio-economic stakeholders in the fisheries sector, NGOs and public authorities that play a crucial role in the implementation of the proposed development strategy. The lead partner of the Belgian FLAG is the Province of West Flanders. The main focus of the FLAG strategy is to add value to local fisheries products and increase local consumption. Belgian landings represent only 10% of fisheries products consumed in Belgium, leaving the remaining 90% to be met by imports. Therefore there is a considerable potential for discovering and developing local markets. It will also support diversification, innovation, the involvement of women and efforts to promote the sustainable management of the marine environment<ref>[https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fpfis/cms/farnet/flagsheet/flag-factsheet-belgium-west-flanders FLAG factsheet - Belgium - West Flanders]</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:FLAG.jpg|center|300px|]] | ||

| + | ::::::::::Fig.4. [https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fpfis/cms/farnet/belgian-flag-factsheet Belgian FLAG area: West Flanders] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

===<span style="color:#3a75c4; Font-size: 130%">'''<small>References</small>'''</span>=== | ===<span style="color:#3a75c4; Font-size: 130%">'''<small>References</small>'''</span>=== | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 10:21, 19 March 2014

Contents

Overview and Background

The Belgian coast is 67 km long and is entirely bordering the province of West-Flanders (region of Flanders, Belgium). The Belgian part of the North Sea is 3,457 km2 (0.5% of the North Sea area), of which more than 1/3 or 1,430 km² are territorial sea within 12 nautical miles distance of the coastline. Belgium currently has 10 coastal municipalities and 4 coastal ports (Nieuwpoort, Oostende, Zeebrugge and Blankenberge), and besides the fish auctions located in Oostende, Zeebrugge and Nieuwpoort where fish is sold according to legal procedures, there are no other dispersed landing points. Although historically the port and auction of Oostende was by far the most important, today the auctions of Zeebrugge (53%) and Oostende (45%) receive the largest share of the landings of Belgian fisheries in Belgian ports.

Belgium has a minor role in the European fisheries context with 0.35% of the total EU production of fish. In 2012, the Belgian commercial sea fishing fleet counted 86 ships, with a total engine capacity of 49,135 kW and gross tonnage of 15,326 GT [1]. 45 vessels are part of the Small Fleet Segment (max 221 kW engine power) of which 2 use passive gear. The remaining 41 vessels belong to the Large Fleet Segment and have an engine power between 221 kW and a maximum of 1,200 kW. This fleet segment represents approximately 80% of the engine power capacity and 77% of the GT of the fleet. While a smaller number use trammel nets (passive gear) and otter trawl, the largest share of the Large Fleet Segment are beam trawl vessels (≥662 kW). The Belgian fleet is highly specialized: more than 68% of the effort(days at sea) and 77% of total landings are achieved by beam trawlers(2010)focusing primarily on flatfish species such as plaice (Pleuronectes platessa) and sole (Solea solea). The results of the reconstruction of the Belgian fleet dynamics since 1830 are presented in Lescrauwaet et al. 2013[2].

The number of days at sea per vessel is fixed at a maximum of 265 per year and in 2011 the entire fleet realized a fishing effort of 15,855 days at sea. In 2011, the Belgian fleet landed a total of 20,138t, of which 16,905t were landed in Belgian ports. Plaice is the most important species in terms of landed weight. The landings of 2011 represented a value of €76.3 million, 14% of which was marketed in foreign ports. Sole generates 47% of the current total value of fisheries in Belgium. The Belgian sea fisheries represent 0.04% of the national Gross Domestic Product [3]. The main fishing grounds in terms of volume of landings in 2010 were in descending order: North Sea South (IVc), Eastern English Channel (VIId), North Sea Central (IVb), Southeast Ireland/Celtic Sea (VIIg) Bristol Channel (VIIf) and Irish Sea (VIIa).

In terms of direct employment, 439 fishers are registered of which approximately 350 are of Belgian nationality. Direct employment in fisheries represent approximately 0.5% of the total employment in the Belgian coastal zone. Another 1040 persons work in the fish processing industry and another 5000 persons in associated trade and services [1]. A historical overview of Belgian sea fisheries is available from [4] and [2].

The Belgian sea fishery sector is rather small compared to that of neighbouring countries in the North Sea and has been gradually losing importance since the Second World War. It is also gradually losing importance relative to the booming tourism industry in the Belgian coastal zone. However fisheries can be an added value to the tourism experience at the coast by developing fisheries-related tourism activities [5]. The present case study of Nieuwpoort (Belgium) analyzes how fisheries is embedded in tourism policy of the municipality.

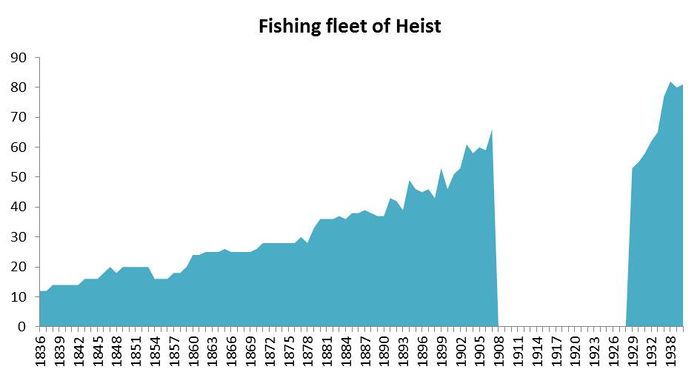

Port description

Heist (Geographical coordinates: 51°20'N 3°14'E) is situated at the eastern part of the Belgian coast and has a population of about 12.900 people. It is part of the municipality Knokke-Heist, which next to Heist and Knokke also comprises the villages Ramskapelle, Westkapelle and Duinbergen. From the 13th century onwards, Heist became known as a relatively important fishing place, despite the absence of an actual port. Traditionally, the fishing vessels moored on the beach. Similar to those of Blankenberge, the boats of Heist had a flat bottom, which made it easier to land on and depart from the beach [6].During a first period of fishery activity, which lasted till the end of the 16th century, the fleet of Heist took part in the important and prosperous Flemish herring fisheries. Circa 1525, Heist had around 10 herring busses (‘haringbuizen’) and 150 fishermen, on a total number of 450 inhabitants [7]. However, due to the religious wars in the second half of the 16th century, this industry vanished in Heist and during the 17th and the first part of the 18th century no active fishermen were reported in this village. With the help of the Austrian government however, the fishing sector in Heist slowly recovered from the second part of the 18th century on [8].This time around, the village focused on fresh fishery with small boats, close to the shore [7].In 1800, 4 of these vessels were counted in Heist. The fleet subsequently grew steadily over the course of the 19th century and in 1905, 60 boats and 234 fishermen were reported [9] (see also graph 1 and 2).

- Fig. 1. and 2. Part of the Heist fishing fleet, moored on the beach (Dekeyzer, 1969).

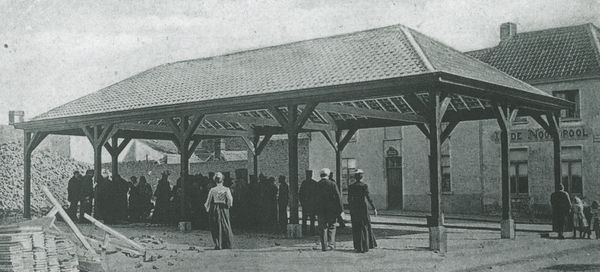

In 1901, Heist even got its own fish auction. The construction and inauguration of the port of Zeebrugge in 1906 eventually halted this flourishing period: more and more ships left Heist for Zeebrugge and after only five years, the Heist fish auction lost its purpose [8] [10]. Eventually, all ships from this town relocated to Zeebrugge. As a result, the typical flat bottomed vessels disappeared in favor of faster ships with keels [6].

- Fig. 3. An image of the Heist fish auction, that only existed for a short number of years (Devent, 1989).

Fishing Fleet

De Zuttere, 1909 documented the evolution of the fishing fleet of Heist from 1836 onwards until 1907. As shown on graph 1 and noted above, the fleet subsequently grew over the course of the 19th century. Fleet data from 1929 onwards are available from the Officieele lijst der visschersvaartuigen documents. In 1940 the last fishing vessels were recorded in Heist. Since then the fishing vessels left Heist and mainly chose Zeebrugge as their home harbor.

Graph 1: Fishing fleet in Heist (Sources: 1836-1907: De Zuttere, 1909; 1929-1940: Officieele lijst der visschersvaartuigen).

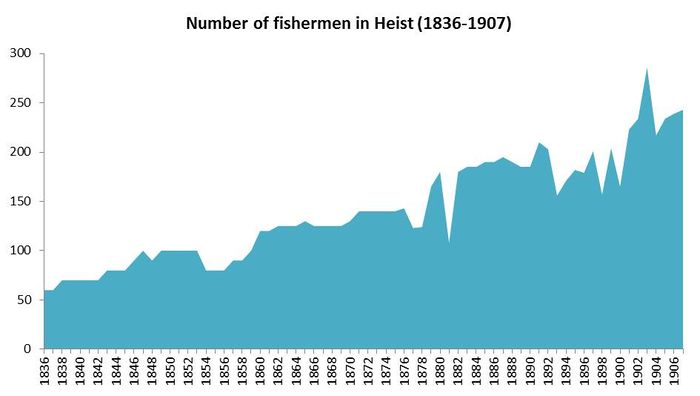

Due to the flourishing fishing activities during the 19th century, a lot of people were employed in the fisheries sector in Heist. Graph 2 illustrates the number of fishermen from 1836 until 1907 (De Zuttere, 1909). The number of fishermen grew steadily over the years, together with the increasing number of ships. Heist counted 286 fishermen in 1903.

- Graph 2: Number of fishermen in Heist (1836-1909). (Source: De Zuttere, 1909)

Fish shops and restaurants

Several fish restaurants can be found in Heist and the rest of the municipality of Knokke-Heist. For example, located on the seawall of Heist, you can find Restaurant Bartholomeus, which recently received its second Michelin star. Chef Bart Desmidt was born and raised at the Belgian shore and grew up in a family of fishermen: both his grandfather and his uncle were fishermen. He prefers to work with local ingredients, such as polder products and North sea fish [11].

There are several fish shops located in the municipality of Knokke-Heist. (click here for an overview). A fish shop in Heist with a long history is Vishandel Depaepe. It was established in Heist in 1928 by Victor Depaepe and is nowadays managed by a fifth generation of this family. The fish shop purchases its fish at the fish auction of Zeebrugge. Apart from a wide range of North sea fish, customers can also find lobsters from Canada, Norway or the Oosterschelde (Eastern Scheldt) and oysters from Zeeland and Normandy.

- Fig. 4. and 5. The fish shop ‘Depaepe’, then and now. (Source: Vishandel Depaepe)

Quality labels

The Flemish brown shrimp is a typical fisheries product in Belgium. In 2006 the Purus label was introduced by a cooperation of ship owners, the cooperative Flemish fisheries organization (Cooperative Vlaamse Visserij Vereniging CVBA) to promote the Flemish unpeeled brown shrimps. The brown shrimps are caught by Belgian fishermen, the fishermen fish no longer than 24 hours and the shrimps are cooked in old Flemish manner (in sea water with salt), there are no additives, preservatives added. This all results in high quality taste. The Purus label also promotes sustainable fishing techniques.

Since 2011, the Flemish Shellfish- and fish cooperation (VSVC) supply, via an exclusive quality label, ‘North Sea Life’, life brown shrimps and swimming crabs to restaurants and wholesalers. Life shrimps allows chefs to determine how they will prepare the shrimps. Life product forms the base of creative and gastronomic possibilities. The same is true for life swimming crabs. In 2013 a minimum of 200 kilo life brown shrimps were landed each day. Prices for life shrimps are on average 30 percent higher than shrimps cooked on board of the shrimp vessel[12].

Organisations

In Belgium, the FLAG, also called the ‘local group’, ‘Plaatselijke Groep Belgisch Zeevisserijgebied’, is a partnership between socio-economic stakeholders in the fisheries sector, NGOs and public authorities that play a crucial role in the implementation of the proposed development strategy. The lead partner of the Belgian FLAG is the Province of West Flanders. The main focus of the FLAG strategy is to add value to local fisheries products and increase local consumption. Belgian landings represent only 10% of fisheries products consumed in Belgium, leaving the remaining 90% to be met by imports. Therefore there is a considerable potential for discovering and developing local markets. It will also support diversification, innovation, the involvement of women and efforts to promote the sustainable management of the marine environment[13].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Roegiers, B.; Platteau, J.; Van Bogaert, T.; Van Gijseghem, D.; Bekaert, K.; De Bruyne, S.; Delbare, D.; Depestele, J.; Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Moreau, K.; Polet, H.; Robbens, J.; Vandamme, S.; Van Hoey, G.; Verschueren, B. (2013). VIRA Visserijrapport 2012 Departement Landbouw en Visserij: Brussel. 98 pp.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lescrauwaet, A.-K. (2013). Belgian fisheries: ten decades, seven seas, forty species: Historical time-series to reconstruct landings, catches, fleet and fishing areas from 1900. PhD Thesis. Ghent University (UGent): Gent. xiii, 242 pp.

- ↑ Anon. (2008). Strategische Milieubeoordeling van het Nationaal Operationeel Plan voor de Belgische visserijsector, 2007 - 2013. ILVO Visserij: Oostende. 103 pp.

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-K.; Debergh, H.; Vincx, M.; Mees, J. (2010). Fishing in the past: Historical data on sea fisheries landings in Belgium. Mar. Policy 34(6): 1279-1289. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2010.05.006

- ↑ Anon. (2011). Europees Visserijfonds (EVF). AS 4: ontwikkelingsstrategie voor het Belgisch kustgebied. Europees Visserijfonds: (s.l.). 33 pp.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Larbouillat, J. (1974). De zeevisserij te Heist. Heemkundig Museum Sincfala: Knokke-Heist. 1-80 pp.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 ‘Evolutie van strand- en kustvisserij’ Sincfala – Museum van de Zwinstreek, consulted on february 19th, 2014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Devent, G. (1989). De Vlaamse zeevisserij. Marc Van de Wiele: Brugge. ISBN 90-6966-061-X. 208 pp.

- ↑ Desnerck, G.; Desnerck, R. (1974). Vlaamse visserij en vissersvaartuigen: 1. De havens. Gaston Desnerck: Oostduinkerke. 256 pp.

- ↑ Hovart, P. (1994). 150 jaar zeevisserijbeheer 1830-1980: een analyse van normatieve bronnen. Mededelingen van het Rijksstation voor Zeevisserij (CLO Gent), 235. Rijksstation voor Zeevisserij: Oostende. 317 pp.

- ↑ Interview with Bart Desmidt, Vlaanderen Vakantieland 2013, consulted on February 20th 2014.

- ↑ http://www.ilvo.vlaanderen.be/NL/Persenmedia/Allemedia/tabid/6294/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/1105/language/nl-NL/ILVO-ziet-in-rauwe-garnaal-meer-dan-lucratieve-niche.aspx#.UyBv6vldVSL

- ↑ FLAG factsheet - Belgium - West Flanders