Difference between revisions of "Ecological impacts of seabed sand mining"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) (Created page with " In many shelf seas bordering low-lying coastal zones with sandy shores, seabed sand is extracted for protecting coastal zones against erosion and flooding. The need for seabe...") |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 11:39, 1 November 2025

In many shelf seas bordering low-lying coastal zones with sandy shores, seabed sand is extracted for protecting coastal zones against erosion and flooding. The need for seabed sand for shore nourishment is growing, as many coastal areas become increasingly vulnerable due to ongoing urban and industrial development and rising sea levels. Increasing portions of the seabed are exploited for sand mining. The ecological impact is therefore an important issue.

Contents

Sand donor North Sea

Three countries on the North Sea - Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany - have adopted the practice of systematic large-scale sand nourishment as primary response to shoreline erosion and the impact of sea level rise. The Netherlands alone extracts more than twenty million cubic meters of sand from the North Sea bed annually. Half of this is intended for beach nourishment, the other half for construction purposes. Because of the structural large-scale sand extraction, most studies on the ecological effects of seabed sand mining have been conducted in the North Sea region.

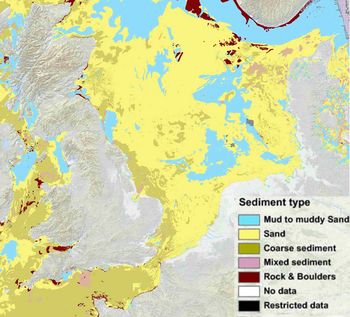

Most parts of the southern and central North Sea have a sandy bottom (Fig. 1). Water movement is dominated by the semidiurnal tide; the amplitude of the tidal currents is typically around 0.5 m/s.

Sand mining for beach nourishment is concentrated in the depth zone between 20 and 30 meters. Targeted sand resources for coastal nourishment have a median grain size in the range 250-500 µm (medium-coarse sand). In the extraction zone, seafloor sediments with these grainsizes are mobile. Sand movement is mainly due to tidal currents, which generate seabed ripples, sandwaves and other bedforms.

The sandy seabed in the depth zone between 20 and 30 meters is a habitat for various macrofauna species. Typical benthic macrofauna of this habitat in the North Sea includes:

- Bristle worms (polychaetes) such as Nephtys,Ophelia, Spiophanes, Aricidea, Glycera, Pisione

- Clams (bivalve molluscs) such as Tellimya, Abra, Spisula, Ensis, Fabulina

- Amphipods (crustaceans) such as Bathyporeia, Urothoe

- Echinoderms such as the brittle stars Ophiura and Amphiura, and the sea urchin Echinocardium cordatum

Ecological recovery of sand mining pits

Sea sand can be extracted from shallow pits (2-4 m below the seafloor) or from deep pits (more than 4 m below the seafloor). In the former case a larger seabed area is mined than in the latter.

Observations show that shallow mining pits (less than 4 m deep) are rapidly filled with sand that has characteristics similar to the pre-mining situation (grainsize 200-500 µm). Seabed life starts recovering soon, driven by local sediment reorganization and colonization by opportunistic species. After 4-8 years, the effect of sand mining has fully dissipated. [1][2]

If the extraction pit does not fill with original surface sediments from its surroundings, recovery towards the original fauna is unlikely, given the tight relationships between benthic fauna and sediments.[3] This is often the case with pits deeper than 4 meters. These pits act as a trap of fine sediments with increased organic content. The amount of available food is higher in these pits, leading to a an increased abundance and total biomass of deposit feeding species such as the sea urchin Echinocardium cordatum, the brittle star Ophiura ophiura and the clam Abra alba, while the fauna in the reference areas is characterized by filter feeding bivalves such as Spisula and Ensis species. [3] Diversity in the pits is lower than in the surroundings, despite the higher abundance.

In areas where extraction targets coarse material, the mining pits are not easily replenished by natural sediment transport. In such cases, both physical and biological recovery processes are slow and the impacts are long-lasting. Even after decades, when species richness and abundance return, the community structure and ecological functions can remain fundamentally altered.[4][5]

Related articles

- Shore nourishment

- Beach nourishment

- Shoreface nourishment

- Threats to the coastal zone

- Nature-based shore protection

References

- ↑ van Dalfsen, J. and Essink, K. 2001. Benthic community response to sand dredging and shoreface nourishment in Dutch coastal waters. Senckenberg. marit. 31: 329–332

- ↑ Lopez, L., Degrendele, K., Roche, M., Barette, F., Van Lancker, V., Terseleer, N. and De Backer, A. 2025. Macrobenthos and morpho-sedimentary recovery dynamics in areas following aggregate extraction cessation. Marine Pollution Bulletin 218, 118184

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Witbaard, R., Moons, S., Kleine Schaars, L. and Craeymeersch, J. 2025. Sedimentary and faunistic effects of medium-deep sand mining along the Dutch Coast. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 321, 109337

- ↑ Barrio Frojan, C.R.S., Cooper, K.M., Bremner, J., Defew, E.C., Hussin, W.M.R.W. and Paterson, D.M. 2011. Assessing the recovery of functional diversity after sustained sediment screening at an aggregate dredging site in the North Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 92: 358–366

- ↑ Mielck, F., Michaelis, R., Hass, H.C., Hertel, S., Ganal, C. and Armonies, W. 2021. Persistent effects of sand extraction on habitats and associated benthic communities in the German Bight. Biogeosciences 18: 3565–3577

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|