Difference between revisions of "Tidal channel meandering and marsh erosion"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) (Created page with " ==Erosion of sheltered marshes== Salt marshes located within estuaries are generally sheltered from strong wave action. Marsh vegetation in sheltered estuarine zones tend...") |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Erosion of sheltered marshes== | ==Erosion of sheltered marshes== | ||

| − | [[Salt marshes]] located within estuaries are | + | [[Salt marshes]] located within estuaries are usually sheltered from strong wave action. This applies to estuaries where the channel width at low water and the maximum wind fetch across the estuary are not much greater than about 1 km<ref>Young, I. R. and L. A. Verhagen 1996. The growth of fetch limited waves in water of finite depth. Part 1. Total energy and peak frequency. Coastal Eng. 29: 47–78</ref>. Marsh vegetation in sheltered estuarine zones tends to colonize mudflats adjacent to the main tidal channel system. As the marsh cliff progresses towards the main tidal channels, it becomes increasingly vulnerable to the scouring effect of tidal currents at the base of the marsh cliff. In this situation, advance and retreat of the marsh cliff are regulated by the dynamics of channel meandering. Gabet (1998<ref>Gabet, E. J. 1998. Lateral migration and bank erosion in a saltmarsh tidal channel in San Francisco Bay, California. Estuaries 21: 745–753</ref>) observed saltmarsh retreat in San Francisco Bay associated with lateral migration of the outside meander of a tidal channel. Erosion proceeded by current-induced undercutting and subsequent slumping of the saltmarsh cliff. Ladd et al. (2021<ref>Ladd, C.J.T., Duggan-Edwards, M.F., Pagès, J.F. and Skov, M.W. 2021. Saltmarsh Resilience to Periodic Shifts in Tidal Channels. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:757715 </ref>) linked saltmarsh retreat with cyclically shifting tidal channels in three macrotidal estuaries in Wales (the Glaslyn-Dwyryd, the Mawddach and the Dyfi). They observed that marsh erosion at the shifting outer channel banks was compensated with marsh accretion at the inner opposite bank or at adjacent inner channel banks. A similar process is observed in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel<ref>Levoy, F., Anthony, E.J., Dronkers, J., Monfort, O. and Montreuil, A-L. 2019. Short-term to Decadal-scale Sand Flat Morphodynamics and Sediment Balance of a Megatidal Bay: Insight from Multiple LiDAR Datasets. Journal of Coastal Research SI 88: 61–76</ref>. Houttuijn Bloemendaal et al. (2023<ref name=H23>Houttuijn Bloemendaal, L. J., FitzGerald, D. M., Hughes, Z. J., Novak, A. B. and Georgiou, I. Y. 2023. Reevaluating the wave power‑salt marsh retreat relationship. Nature Scientific Reports 13, 2884</ref>) found a strong correlation of marsh retreat with local tidal channel curvature in the Great Marsh in Massachusetts (USA). |

| + | |||

| + | In wide microtidal lagoons, such as the Venice Lagoon, marsh erosion is mainly associated with wave action<ref>Marani, M., D’Alpaos, A., Lanzoni, S. and Santalucia, M. 2011. Understanding and predicting wave erosion of marsh edge. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L21401</ref><ref>Bendoni, M., Mel, R., Solari, L., Lanzoni, S., Francalanci, S. and Oumeraci, H. 2016. Insights into lateral marsh retreat mechanism through localized field measurements. Water Resour. Res. 52: 1446–1464</ref>. Other phenomena that influence marsh erosion include sediment composition, bulk density and height of the marsh cliff, adjacent water depth, vegetation, bioturbation and local human activities<ref name=H23/>. | ||

==Dynamics of channel meandering== | ==Dynamics of channel meandering== | ||

| Line 7: | Line 9: | ||

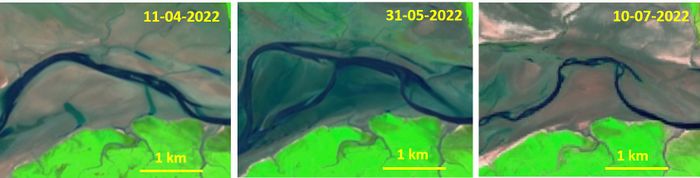

[[File:TidalBendFlow.jpg|thumb|right|450px|Fig. 1. Schematic representation of tidal flow and sediment transport in a channel bend. a: flood flow path; b: ebb flow path; c: horizontal pattern of residual fluid flow (blue) and net sediment transport (yellow); d: vertical cross-channel pattern of residual flow (blue) and net sediment transport (yellow). Red = erosion; Green=accretion.]] | [[File:TidalBendFlow.jpg|thumb|right|450px|Fig. 1. Schematic representation of tidal flow and sediment transport in a channel bend. a: flood flow path; b: ebb flow path; c: horizontal pattern of residual fluid flow (blue) and net sediment transport (yellow); d: vertical cross-channel pattern of residual flow (blue) and net sediment transport (yellow). Red = erosion; Green=accretion.]] | ||

| − | Channel meandering results from inertia, the natural propensity of the flow to follow with delay the curvature of a bending channel. The flow is then concentrated just downstream of the location of maximum channel curvature. At this location the channel wall is subject to strong shear stress. If the channel | + | Channel meandering results from inertia, the natural propensity of the flow to follow with delay the curvature of a bending channel. The flow is then concentrated at the outer channel bend just downstream of the location of maximum channel curvature. At this location the channel wall is subject to strong shear stress. This occurs for flood and ebb flow alike, see Fig. 1a and 1b. If the outer channel bend is formed by a marsh cliff, shear-induced erosion will primarily erode the cliff base; subsequent cliff collapse by slumping or toppling is often preceded by tension cracks propagating down from the cliff top when the critical tensile strength of the bank soil is exceeded<ref>Langendoen, E.J. and Simon, A. 2008. Modeling the evolution of incised streams. II: streambank erosion. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 134: 905–915</ref>. Several other geotechnical processes contribute to bank instability, notably tidal water level variations and delayed soil pore pressures relative to the external water level. During ebb (water level drawdown), the bank slope is subject to excess porewater pressure, resulting in outward seepage, suction stress in the unsaturated zone and development of tension cracks. During rising water, the bank soil becomes saturated and the porewater pressure increases, resulting in loss of matric suction and decreased soil shear strength<ref>Johansson, J. 2014. Impact of Water-Level Variations on Slope Stability. Licentiate Thesis, Lulea University of Technology</ref><ref name=Z22>Zhao, K., Coco, G., Gong, Z., Darby, S. E., Lanzoni, S., Xu, F., Zhang, K. and Townend, I. 2022. A review on bank retreat: Mechanisms, observations, and modeling. Reviews of Geophysics 60, e2021RG000761</ref>. Due to these mechanisms, the outer channel bend will erode, and the channel meander will thus become larger. Marsh vegetation stabilizes channel bend cliffs in several ways; it can retard the erosion process, but generally will not prevent it<ref name=Z22/>. |

| + | |||

| + | Figure 1c shows a schematic picture of the residual horizontal flow circulation at a channel bend. Superimposed on the tidal flow, the residual flow circulation produces a strong net sediment transport that contributes to removing eroded sediment (collapsed bank soil) from the outer channel bend. The residual sediment transport converges at the inner channel bend where a point bar develops. Tidal flow at a channel bend also produces a residual flow circulation in the vertical cross-channel plane, which provides an additional contribution to sediment transfer from the outer to the inner channel bend (Fig. 1d). The channel bend configuration thus produces feedback to fluid flow and sediment transport that enlarges the channel meander. When a meander becomes too large, eventually a chute channel (shortcut channel through the point bar) will develop that cuts off the meander<ref>Kleinhans, M.G. and van den Berg, J.H. 2011. River channel and bar patterns explained and predicted by an empirical and a physics-based method. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 36: 721-738</ref>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The process depicted in Fig. 1 holds for tidal channels that guide the flow throughout the tidal cycle, as is generally the case for the main estuarine channels and most tidal marsh creeks. The situation is different for shallow, non-embanked channels with a mean depth much smaller than the tidal range. This may be the case for mudflat creeks that are subject to significant cross-channel flow at elevated tide levels. These mudflat creeks can develop meanders due to channel-flow interaction processes driven by strong ebb currents at the final stages of mudflat emptying<ref>Kleinhans, M. G., Schuurman, F., Bakx, W. and Markies, H. 2009. Meandering channel dynamics in highly cohesive sediment on an intertidal mud flat in the Westerschelde estuary, The Netherlands. Geomorphology 105: 261–276</ref><ref>Gao, C., Finotello, A., D’Alpaos, A., Ghinassi, M., Carniello, L., Pan, Y., Chen, D. and Wang, Y.P. 2022. Hydrodynamics of meander bends in intertidal mudflats: A field study from the macrotidal Yangkou Coast, China. Water Resources Research 58, e2022WR033234</ref>. | ||

| − | A numerical model simulation of the development of tidal channel meanders is shown in the article [[Estuarine morphological modelling]]. This simulation illustrates the inherent instability of straight non-curving channels; meandering can be triggered by infinitesimal small irregularities in the channel alignment. For a mathematical treatment of this phenomenon the reader is referred to the literature, e.g., <ref>Ikeda, S., Parker, G. and Sawai, K. 1981. Bend theory of river meanders. Part 1. Linear development. J. Fluid Mech. 112: 363-377</ref><ref>Dronkers, J. 2017. Dynamics of Coastal Systems. Advanced Series on Ocean Engineering 41. World Scientific</ref>. The inherent instability of meandering channels can produce shifts in the channel pattern with a high degree of randomness, as illustrated in Fig. 2. | + | A numerical model simulation of the development of tidal channel meanders is shown in the article [[Estuarine morphological modelling]]. This simulation illustrates the inherent instability of straight non-curving channels; meandering can be triggered by infinitesimal small irregularities in the channel alignment. For a mathematical treatment of this phenomenon the reader is referred to the literature, e.g., Ikeda et al. (1981<ref>Ikeda, S., Parker, G. and Sawai, K. 1981. Bend theory of river meanders. Part 1. Linear development. J. Fluid Mech. 112: 363-377</ref>), Dronkers (2017<ref>Dronkers, J. 2017. Dynamics of Coastal Systems. Advanced Series on Ocean Engineering 41. World Scientific</ref>) and references therein. Explicit modeling of the various geotechnical processes contributing to channel meandering is quite complicated and hampered by knowledge gaps<ref>Lai, Y.G., Thomas, R.E., Ozeren, Y., Simon, A., Greimann, B.P. and Wu, K. 2015. Modeling of multilayer cohesive bank erosion with a coupled bank stability and mobile-bed model. Geomorphology 243: 116–129</ref>; mainstream numerical morphodynamic models use crude parameterizations that require field data for calibration. The inherent instability of meandering channels can produce shifts in the channel pattern with a high degree of randomness, as illustrated in Fig. 2. |

| Line 18: | Line 24: | ||

Meandering of channels that are deeply scoured in well-consolidated sediment is a very slow process. Lateral channel shifts in one year are typically less than about 10% of the channel width<ref>Finotello, A., Lanzoni, S., Ghinassi, M., Marani, M., Rinaldo, A, and D'Alpaos, A. 2017. Field migration rates of tidal meanders recapitulate fluvial morphodynamics. PNAS 115: 1463-1468</ref>. Observed rates of marsh retreat are of the same order of magnitude; reported values are in the range 0.1-3 m/yr <ref>Fagherazzi, S., FitzGerald, D.M., Fulweiler, R.W., Hughes, Z., Wiberg, P.L., McGlathery, K.J., Morris, J.T., Tolhurst, T.J., Deegan, L.A., Johnson, D.S., Lesser, J.S. and Nelson, J.A. 2022. Ecogeomorphology of Salt Marshes. Ch. 8.14 of Treatise on Geomorphology (ed. Shroder, J.F.), Elsevier</ref>. | Meandering of channels that are deeply scoured in well-consolidated sediment is a very slow process. Lateral channel shifts in one year are typically less than about 10% of the channel width<ref>Finotello, A., Lanzoni, S., Ghinassi, M., Marani, M., Rinaldo, A, and D'Alpaos, A. 2017. Field migration rates of tidal meanders recapitulate fluvial morphodynamics. PNAS 115: 1463-1468</ref>. Observed rates of marsh retreat are of the same order of magnitude; reported values are in the range 0.1-3 m/yr <ref>Fagherazzi, S., FitzGerald, D.M., Fulweiler, R.W., Hughes, Z., Wiberg, P.L., McGlathery, K.J., Morris, J.T., Tolhurst, T.J., Deegan, L.A., Johnson, D.S., Lesser, J.S. and Nelson, J.A. 2022. Ecogeomorphology of Salt Marshes. Ch. 8.14 of Treatise on Geomorphology (ed. Shroder, J.F.), Elsevier</ref>. | ||

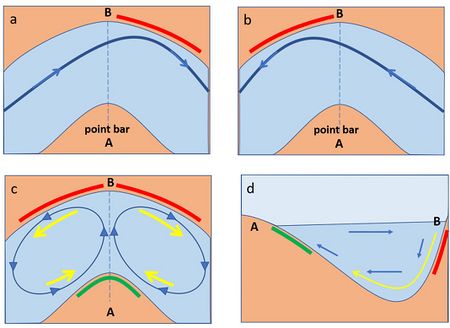

| − | Channels in tidal basins filled with fine non-cohesive sediment display a highly dynamic meander pattern. An example is the megatidal bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (France). A large tidal flat system at the bay head | + | Channels in tidal basins filled with fine non-cohesive sediment display a highly dynamic meander pattern. An example is the megatidal bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (France). A large tidal flat system at the bay head contains a high proportion (about 50%) of very fine carbonate sand (0.1-0.15 mm) and carbonate silt (so-called 'tangue', 0.03-0.09 mm) which is low-cohesive and highly mobile<ref>Larsonneur C. 1989. La Baie du Mont Saint-Michel. Bull. Inst. Geol. Bassin Aquit. 46: 1-75</ref>. The tidal channels therefore remain shallow and can easily shift over great distances in response to small perturbations. The highly dynamic nature of the channel pattern is illustrated in Fig. 2, showing channel shifts of more than 100 m in a single month. |

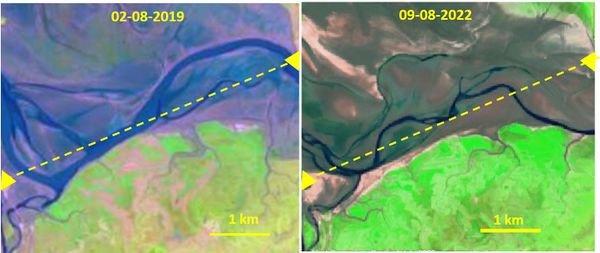

Marsh vegetation in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel tends to progress from the upper tidal flats to the interior of the bay. The bay area occupied by salt marshes has strongly increased over the past century. Their extent is limited by the meandering channel system. Fig. 3 illustrates marsh retreat in the southern part of the bay caused by meandering channels that undermine and eventually erode the marsh cliffs. See also [[French case studies: Upper tidal flat evolution in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (NW France)]]. | Marsh vegetation in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel tends to progress from the upper tidal flats to the interior of the bay. The bay area occupied by salt marshes has strongly increased over the past century. Their extent is limited by the meandering channel system. Fig. 3 illustrates marsh retreat in the southern part of the bay caused by meandering channels that undermine and eventually erode the marsh cliffs. See also [[French case studies: Upper tidal flat evolution in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (NW France)]]. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:37, 20 August 2025

Contents

Erosion of sheltered marshes

Salt marshes located within estuaries are usually sheltered from strong wave action. This applies to estuaries where the channel width at low water and the maximum wind fetch across the estuary are not much greater than about 1 km[1]. Marsh vegetation in sheltered estuarine zones tends to colonize mudflats adjacent to the main tidal channel system. As the marsh cliff progresses towards the main tidal channels, it becomes increasingly vulnerable to the scouring effect of tidal currents at the base of the marsh cliff. In this situation, advance and retreat of the marsh cliff are regulated by the dynamics of channel meandering. Gabet (1998[2]) observed saltmarsh retreat in San Francisco Bay associated with lateral migration of the outside meander of a tidal channel. Erosion proceeded by current-induced undercutting and subsequent slumping of the saltmarsh cliff. Ladd et al. (2021[3]) linked saltmarsh retreat with cyclically shifting tidal channels in three macrotidal estuaries in Wales (the Glaslyn-Dwyryd, the Mawddach and the Dyfi). They observed that marsh erosion at the shifting outer channel banks was compensated with marsh accretion at the inner opposite bank or at adjacent inner channel banks. A similar process is observed in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel[4]. Houttuijn Bloemendaal et al. (2023[5]) found a strong correlation of marsh retreat with local tidal channel curvature in the Great Marsh in Massachusetts (USA).

In wide microtidal lagoons, such as the Venice Lagoon, marsh erosion is mainly associated with wave action[6][7]. Other phenomena that influence marsh erosion include sediment composition, bulk density and height of the marsh cliff, adjacent water depth, vegetation, bioturbation and local human activities[5].

Dynamics of channel meandering

Channel meandering results from inertia, the natural propensity of the flow to follow with delay the curvature of a bending channel. The flow is then concentrated at the outer channel bend just downstream of the location of maximum channel curvature. At this location the channel wall is subject to strong shear stress. This occurs for flood and ebb flow alike, see Fig. 1a and 1b. If the outer channel bend is formed by a marsh cliff, shear-induced erosion will primarily erode the cliff base; subsequent cliff collapse by slumping or toppling is often preceded by tension cracks propagating down from the cliff top when the critical tensile strength of the bank soil is exceeded[8]. Several other geotechnical processes contribute to bank instability, notably tidal water level variations and delayed soil pore pressures relative to the external water level. During ebb (water level drawdown), the bank slope is subject to excess porewater pressure, resulting in outward seepage, suction stress in the unsaturated zone and development of tension cracks. During rising water, the bank soil becomes saturated and the porewater pressure increases, resulting in loss of matric suction and decreased soil shear strength[9][10]. Due to these mechanisms, the outer channel bend will erode, and the channel meander will thus become larger. Marsh vegetation stabilizes channel bend cliffs in several ways; it can retard the erosion process, but generally will not prevent it[10].

Figure 1c shows a schematic picture of the residual horizontal flow circulation at a channel bend. Superimposed on the tidal flow, the residual flow circulation produces a strong net sediment transport that contributes to removing eroded sediment (collapsed bank soil) from the outer channel bend. The residual sediment transport converges at the inner channel bend where a point bar develops. Tidal flow at a channel bend also produces a residual flow circulation in the vertical cross-channel plane, which provides an additional contribution to sediment transfer from the outer to the inner channel bend (Fig. 1d). The channel bend configuration thus produces feedback to fluid flow and sediment transport that enlarges the channel meander. When a meander becomes too large, eventually a chute channel (shortcut channel through the point bar) will develop that cuts off the meander[11].

The process depicted in Fig. 1 holds for tidal channels that guide the flow throughout the tidal cycle, as is generally the case for the main estuarine channels and most tidal marsh creeks. The situation is different for shallow, non-embanked channels with a mean depth much smaller than the tidal range. This may be the case for mudflat creeks that are subject to significant cross-channel flow at elevated tide levels. These mudflat creeks can develop meanders due to channel-flow interaction processes driven by strong ebb currents at the final stages of mudflat emptying[12][13].

A numerical model simulation of the development of tidal channel meanders is shown in the article Estuarine morphological modelling. This simulation illustrates the inherent instability of straight non-curving channels; meandering can be triggered by infinitesimal small irregularities in the channel alignment. For a mathematical treatment of this phenomenon the reader is referred to the literature, e.g., Ikeda et al. (1981[14]), Dronkers (2017[15]) and references therein. Explicit modeling of the various geotechnical processes contributing to channel meandering is quite complicated and hampered by knowledge gaps[16]; mainstream numerical morphodynamic models use crude parameterizations that require field data for calibration. The inherent instability of meandering channels can produce shifts in the channel pattern with a high degree of randomness, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Illustration of marsh erosion by channel meandering

Meandering of channels that are deeply scoured in well-consolidated sediment is a very slow process. Lateral channel shifts in one year are typically less than about 10% of the channel width[17]. Observed rates of marsh retreat are of the same order of magnitude; reported values are in the range 0.1-3 m/yr [18].

Channels in tidal basins filled with fine non-cohesive sediment display a highly dynamic meander pattern. An example is the megatidal bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (France). A large tidal flat system at the bay head contains a high proportion (about 50%) of very fine carbonate sand (0.1-0.15 mm) and carbonate silt (so-called 'tangue', 0.03-0.09 mm) which is low-cohesive and highly mobile[19]. The tidal channels therefore remain shallow and can easily shift over great distances in response to small perturbations. The highly dynamic nature of the channel pattern is illustrated in Fig. 2, showing channel shifts of more than 100 m in a single month.

Marsh vegetation in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel tends to progress from the upper tidal flats to the interior of the bay. The bay area occupied by salt marshes has strongly increased over the past century. Their extent is limited by the meandering channel system. Fig. 3 illustrates marsh retreat in the southern part of the bay caused by meandering channels that undermine and eventually erode the marsh cliffs. See also French case studies: Upper tidal flat evolution in the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (NW France).

Related articles

References

- ↑ Young, I. R. and L. A. Verhagen 1996. The growth of fetch limited waves in water of finite depth. Part 1. Total energy and peak frequency. Coastal Eng. 29: 47–78

- ↑ Gabet, E. J. 1998. Lateral migration and bank erosion in a saltmarsh tidal channel in San Francisco Bay, California. Estuaries 21: 745–753

- ↑ Ladd, C.J.T., Duggan-Edwards, M.F., Pagès, J.F. and Skov, M.W. 2021. Saltmarsh Resilience to Periodic Shifts in Tidal Channels. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:757715

- ↑ Levoy, F., Anthony, E.J., Dronkers, J., Monfort, O. and Montreuil, A-L. 2019. Short-term to Decadal-scale Sand Flat Morphodynamics and Sediment Balance of a Megatidal Bay: Insight from Multiple LiDAR Datasets. Journal of Coastal Research SI 88: 61–76

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Houttuijn Bloemendaal, L. J., FitzGerald, D. M., Hughes, Z. J., Novak, A. B. and Georgiou, I. Y. 2023. Reevaluating the wave power‑salt marsh retreat relationship. Nature Scientific Reports 13, 2884

- ↑ Marani, M., D’Alpaos, A., Lanzoni, S. and Santalucia, M. 2011. Understanding and predicting wave erosion of marsh edge. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L21401

- ↑ Bendoni, M., Mel, R., Solari, L., Lanzoni, S., Francalanci, S. and Oumeraci, H. 2016. Insights into lateral marsh retreat mechanism through localized field measurements. Water Resour. Res. 52: 1446–1464

- ↑ Langendoen, E.J. and Simon, A. 2008. Modeling the evolution of incised streams. II: streambank erosion. J. Hydraul. Eng. ASCE 134: 905–915

- ↑ Johansson, J. 2014. Impact of Water-Level Variations on Slope Stability. Licentiate Thesis, Lulea University of Technology

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Zhao, K., Coco, G., Gong, Z., Darby, S. E., Lanzoni, S., Xu, F., Zhang, K. and Townend, I. 2022. A review on bank retreat: Mechanisms, observations, and modeling. Reviews of Geophysics 60, e2021RG000761

- ↑ Kleinhans, M.G. and van den Berg, J.H. 2011. River channel and bar patterns explained and predicted by an empirical and a physics-based method. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 36: 721-738

- ↑ Kleinhans, M. G., Schuurman, F., Bakx, W. and Markies, H. 2009. Meandering channel dynamics in highly cohesive sediment on an intertidal mud flat in the Westerschelde estuary, The Netherlands. Geomorphology 105: 261–276

- ↑ Gao, C., Finotello, A., D’Alpaos, A., Ghinassi, M., Carniello, L., Pan, Y., Chen, D. and Wang, Y.P. 2022. Hydrodynamics of meander bends in intertidal mudflats: A field study from the macrotidal Yangkou Coast, China. Water Resources Research 58, e2022WR033234

- ↑ Ikeda, S., Parker, G. and Sawai, K. 1981. Bend theory of river meanders. Part 1. Linear development. J. Fluid Mech. 112: 363-377

- ↑ Dronkers, J. 2017. Dynamics of Coastal Systems. Advanced Series on Ocean Engineering 41. World Scientific

- ↑ Lai, Y.G., Thomas, R.E., Ozeren, Y., Simon, A., Greimann, B.P. and Wu, K. 2015. Modeling of multilayer cohesive bank erosion with a coupled bank stability and mobile-bed model. Geomorphology 243: 116–129

- ↑ Finotello, A., Lanzoni, S., Ghinassi, M., Marani, M., Rinaldo, A, and D'Alpaos, A. 2017. Field migration rates of tidal meanders recapitulate fluvial morphodynamics. PNAS 115: 1463-1468

- ↑ Fagherazzi, S., FitzGerald, D.M., Fulweiler, R.W., Hughes, Z., Wiberg, P.L., McGlathery, K.J., Morris, J.T., Tolhurst, T.J., Deegan, L.A., Johnson, D.S., Lesser, J.S. and Nelson, J.A. 2022. Ecogeomorphology of Salt Marshes. Ch. 8.14 of Treatise on Geomorphology (ed. Shroder, J.F.), Elsevier

- ↑ Larsonneur C. 1989. La Baie du Mont Saint-Michel. Bull. Inst. Geol. Bassin Aquit. 46: 1-75

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|