Difference between revisions of "Undertow"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ Definition| title = Undertow | {{ Definition| title = Undertow | ||

| − | | definition = Undertow is the current flowing offshore near the seabed in the [[surf zone]], driven by | + | | definition = Undertow is the current flowing offshore near the seabed in the [[surf zone]], mainly driven by [[wave set-up]] at the shoreline, and compensating for onshore mass transport by wave crests and wave bores.}} |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | The undertow is a net circulation in the cross-shore vertical plane representing a mechanism for | + | The undertow is a net circulation in the cross-shore vertical plane representing a mechanism for compensating the wave-induced net onshore mass transport in the surf zone. This onshore transport is due to the phase relationship between wave surface elevation and wave orbital velocity (Stokes' drift) and to roller transport (Appendix Eq. 13). Another possible mechanism for compensating wave-induced onshore transport is the occurrence of [[rip current]] circulations. |

| − | + | When standing just seaward of the shoreline in the surf zone, one can clearly feel the onshore surface current as a wave crest arrives, and the seaward current near the bottom that occurs beneath the next wave trough. | |

| − | The undertow | + | There is no generally applicable formula for the undertow velocity, as it depends on the particular shoreface morphology. The main driving force for the undertow is the wave set-up at the shoreline. The [[wave set-up]] results from the gradient in the net onshore momentum flux ([[radiation stress]]) due to wave energy dissipation and from the onshore shear stress produced by the [[Wave set-up#Effect of the surface roller|wave bore roller]]<ref name=S1>Svendsen, I.A. 1984. Wave heights and set-up in a surf zone. Coast. Eng. 8: 303–329</ref><ref>Apotsos, A., Raubenheimer, B., Elgar, S., Guza, R.T. and Smith, J.A. 2007. Effects of wave rollers and bottom stress on wave setup. J. Geophysical Research 112, C02003</ref>, as shown in the Appendix (Eq. 12). |

| + | |||

| + | Undertow is a major mechanism for beach erosion under storm conditions, see [[Shoreface profile]]. The strength of offshore sediment transport under storm condition is due to the strong (more than linear) dependence of the undertow on wave height (Appendix Eqs. 12, 13) and on the high suspended sediment concentrations induced by wave breaking<ref>van der Zanden, J., van der A, D. A., Hurther, D., Caceres, I., O’Donoghue, T. and Ribberink, J. S. 2017. Suspended sediment transport around a large-scale laboratory breaker bar. Coastal Engineering 125: 51–69</ref>. | ||

==Related articles== | ==Related articles== | ||

| + | :[[Wave set-up]] | ||

:[[Shoreface profile]] | :[[Shoreface profile]] | ||

| + | :[[Radiation stress]] | ||

| + | :[[Breaker index]] | ||

| + | :[[Wave transformation]] | ||

:[[Shallow-water wave theory]] | :[[Shallow-water wave theory]] | ||

:[[Currents]] | :[[Currents]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | ==Appendix: | + | |

| + | ==Appendix: Undertow equations== | ||

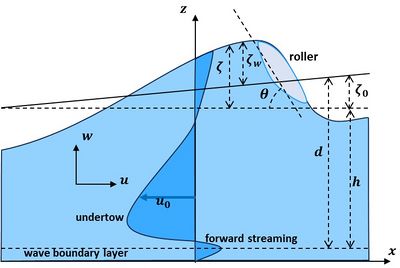

[[File:UndertowSymbols.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Fig. 1. Definition sketch for the momentum balance equations.]] | [[File:UndertowSymbols.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Fig. 1. Definition sketch for the momentum balance equations.]] | ||

| − | This appendix reproduces the shallow-water equations from which the undertow can be determined. The equations refer to shore-normal wave incidence on a uniform coast (no longshore current) | + | This appendix reproduces the shallow-water equations from which the undertow can be determined. The equations refer to shore-normal wave incidence on a uniform coast (no longshore current). The driving force is a surface wave incident from the far field, |

| + | |||

| + | <math>\eta_w (x,t) = \dfrac{H}{2} \cos(\omega t – k x)</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Symbols are defined in Fig. 1, | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>x=</math> shore-perpendicular onshore coordinate, <math>z=</math> vertical upward coordinate, <math>H=</math> wave height, <math>h=</math> still water depth, <math>g=</math> gravitational acceleration, <math>c \approx \sqrt{gh}=</math> wave celerity, <math>\omega=2 \pi /T = k \, c =</math> wave radial frequency, <math>k= 2 \pi /L=</math> wave number, <math>p(x,z,t)=</math> pressure, <math>\; u(x,z,t), \, w(x,z,t) \,=</math> horizontal, vertical velocity; <math>\big\langle … \big\rangle \, =</math> wave-averaged value (averaged over one or more wave cycles, encompassing the turbulence time scale), <math>\; u_0 = <u>, \, w_0=<w></math>, <math>\; u_w, \, w_w \,=</math> horizontal, vertical wave orbital velocities, <math>\; u', \, w' \, =</math> turbulent velocity fluctuations. | ||

| − | The velocities <math>u, \, w</math> and surface elevation <math>\ | + | The velocities <math>u, \, w</math> and surface elevation <math>\eta</math> are decomposed as |

| − | <math>u = u_0 + u_w+u' \, , \; w = w_0 + w_w +w' \, , \; \ | + | <math>u = u_0 + u_w+u' \, , \; w = w_0 + w_w +w' \, , \; \eta = \eta_u + \eta_w \, , \; \eta_u = \langle \eta \rangle . \qquad (1)</math> |

| − | The | + | The momentum balance equations in the propagation direction and in the vertical direction are |

| − | <math>\ | + | <math>\dfrac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \dfrac{\partial u^2}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w u}{\partial z} + \dfrac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial x} = 0 \, .\qquad (2)</math> |

| − | + | <math>\dfrac{\partial w}{\partial t} + \dfrac{\partial u w}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w^2}{\partial z} + \dfrac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial z} = -g \, . \qquad (3)</math> | |

| − | <math> | + | The continuity equation is <math>\quad \dfrac{\partial u}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w}{\partial z} =0 \, . \quad</math> The wave motion above the boundary layer is assumed to be irrotational, <math>\quad \dfrac{\partial u}{\partial z} = \dfrac{\partial w}{\partial x} \, . </math> |

| − | <math>\ | + | From these equations one finds <math>\quad \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} (u_w w_w) = - \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial }{\partial x} (u_w^2 - w_w^2) \; , \quad \dfrac{\partial }{\partial x} (u_w w_w) = \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} (u_w^2 - w_w^2) \, . \qquad (4)</math> |

| − | + | Substitution in Eqs. (2,3) and averaging over the wave cycle gives | |

| − | + | <math>\dfrac{\partial u_0^2}{\partial x} + \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \langle u_w^2 + w_w^2\rangle + \frac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial \langle p \rangle }{\partial x} = - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} \langle u'w' \rangle \, .\qquad (5)</math> | |

| − | + | <math>\frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} \langle u_w^2 + w_w^2 \rangle + \frac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial \langle p \rangle }{\partial z} = -g \, .\qquad (6)</math> | |

| − | <math> | + | The pressure <math>\langle p \rangle</math> is determined by integration of Eq. (6). Differentiation with respect to <math>x</math> and substitution in Eq. (5) gives |

| − | + | <math>\dfrac{\partial u_0^2}{\partial x} + \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \langle u_w^2(\eta) + w_w^2(\eta) \rangle + g \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} = - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} \langle u'w' \rangle \, .\qquad (7)</math> | |

| − | <math>\ | + | The term <math>\tau= - \rho \langle u'w' \rangle </math> represents the turbulent shear stress that diffuses momentum from the net circulation <math>u_0(x,z)</math> over the vertical. This can represented to a first approximation by a gradient-type diffusion with an eddy-viscosity coefficient <math>K(x,z)</math>, |

| − | + | <math>\tau = \rho \, K(x,z) \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} \, , \qquad (8)</math> | |

| − | <math> | + | The net circulation <math>u_0</math> can now be obtained from the modified Bernoulli equation (7), which is rewritten as |

| − | |||

| − | + | <math> \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z}K(x,z) \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} u_0^2 = \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \langle u_w^2(\eta) + w_w^2(\eta) \rangle + g \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} \, .\qquad (9)</math> | |

| − | |||

| − | <math> | ||

| − | + | To solve this equation, the eddy-viscosity coefficient <math>K(x,z)</math> and the function <math>\partial \langle u_w^2(\eta) + w_w^2(\eta) \rangle / \partial x </math> must be known. These functions can be determined by numerically solving the Eqs. (2,3) or determined from field or laboratory measurements<ref name=SW>Stive, M. J. F. and Wind, H.G. 1986. Cross-shore mean flow in the surf zone. Coastal Eng. 10: 325– 340</ref><ref name=W17>van der Werf, J., Ribberink, J., Kranenburg, W., Neessen, K. and Boers, M. 2017. Contributions to the wave-mean momentum balance in the surf zone. Coastal Engineering 121: 212–220</ref>. | |

| − | a | + | Approximate analytical expressions have been derived using [[shallow-water wave theory]] outside the near-bed wave boundary layer and assuming that bed slope effects can be neglected<ref name=S1>Svendsen, I.A. 1984. Wave heights and set-up in a surf zone. Coast. Eng. 8: 303–329</ref><ref name=S2>Svendsen, I.A. 1984. Mass flux and undertow in a surf zone. Coast. Eng. 8: 347–365</ref><ref name=D89>Deigaard, R. and Fredsoe, J. 1989. Shear Stress Distribution in Dissipative Water Waves. Coastal Eng. 13: 357-378</ref>. |

| − | + | According to shallow-water wave theory, we approximate the wave energy <math>E_w=\rho g H^2 /8</math> and <math> \langle w^2(\eta) \rangle << \langle u^2(\eta) \rangle \approx E_w /(\rho h)</math>. Assuming that wave energy is mainly lost through depth-induced wave breaking (see [[Breaker index]]), | |

| − | <math>\ | + | <math>\dfrac{dE_w}{dx} \approx - \dfrac{2 H E_w}{ h c T} \approx - \dfrac{\rho c h}{4 T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3</math> and <math>\dfrac{d \langle u^2(\eta) \rangle }{dx} \approx \dfrac{1}{\rho h } \dfrac{d E_w}{dx} \approx \dfrac{c}{4 T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 \, . \qquad (10)</math> |

| − | The | + | The [[wave set-up]] <math>d \eta_u / dx</math> is related to the [[radiation stress]] <math>S_{xx}</math> resulting from breaker-induced wave dissipation (see [[Wave set-up]]), |

| − | + | <math> g \rho d \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} = - \dfrac{d}{dx} S_{xx} + \langle \tau_s \rangle - \langle \tau_b \rangle \; , \quad \dfrac{d}{dx} S_{xx} \approx \dfrac{3}{2} \dfrac{dE_w}{dx} \approx -\dfrac{3c}{8T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 \, . \qquad (11)</math> | |

| − | <math>\ | + | The breaker-induced surface shear stress is given by<ref>Duncan, J.H. 1981. An experimental investigation of breaking waves produced by a towed hydrofoil. Proc. R. Sot. London A, 377: 331-348</ref> <math>\quad \langle \tau_s \rangle = \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{h} E_r \, , \;</math> where the roller energy <math>\; E_r \approx \dfrac{\rho A c}{2T} \, \;</math> and <math>\theta</math> the roller steepness angle (inclination angle of the bore front). |

| − | The | + | The water volume <math>A</math> of the [[Wave set-up#Effect of the surface roller|wave bore roller]] (water volume per longshore meter) is estimated as being close to the square of the bore height. |

| − | + | ||

| + | The approximate analytical undertow equation (9) finally becomes | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\quad \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z}K(x,z) \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} u_0^2 + \dfrac{\langle \tau_b \rangle }{\rho h} = \dfrac{c}{4T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 + \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{\rho h^2} E_r \, . \qquad (12)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Zou et al. (2006<ref name=Z6>Zou, Q., Bowen, A.J. and Hay, A.E. 2006. Vertical distribution of wave shear stress in variable water depth: theory and observations. J. Geophys. Res. 111: 1–17</ref>) give more elaborate analytical expressions that include the effect of a seabed slope. The bed slope effect appears to be important when comparing results with field observations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Two boundary conditions are needed to solve the second order differential equation (12). At the seabed, <math>z=-h</math>, the undertow velocity vanishes, <math>u_0(z=-h)=0</math>. The second condition is the overall mass balance represented by the equation | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>\int_{-h}^0 u_0(z) dz \approx - \langle (h+\eta)u_w \rangle - \dfrac{A}{T} \approx - \dfrac{c H^2}{8h} - \dfrac{A}{T} \, . \qquad (13)</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This expression includes the mass transport by the roller, representing the roller volume <math>A</math> which is transported onshore with the wave bore (crest of the broken wave, moving with celerity <math>c</math>).<ref name=S1>Svendsen, I.A. 1984. Wave heights and set-up in a surf zone. Coast. Eng. 8: 303–329</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A qualitative impression of the undertow velocity profile can be derived from the vertical distribution of the eddy viscosity <math>K(z)</math>. If the eddy viscosity is assumed uniform over the vertical, the undertow velocity <math>u_0(z)</math> has a parabolic profile, because the r.h.s. of Eq. (12) does not depend on <math>z</math> in the analytic model. However, as most turbulence is generated by wave breaking near the water surface, the eddy viscosity is more likely a decreasing function with depth<ref name=D91>Deigaard, R., Justesen, P. and Fredsoe, J. 1991. Modelling of undertow by a one-equation turbulence model. Coast. Eng. 15: 431-458</ref>. In this case, the strongest variation of the undertow (greatest gradient) is close to the seabed, as sketched in Fig.1. This undertow profile, with maximum offshore velocity in the lower part of the vertical, best matches observations. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 102: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

Latest revision as of 16:55, 9 November 2025

Definition of Undertow:

Undertow is the current flowing offshore near the seabed in the surf zone, mainly driven by wave set-up at the shoreline, and compensating for onshore mass transport by wave crests and wave bores.

This is the common definition for Undertow, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

Notes

The undertow is a net circulation in the cross-shore vertical plane representing a mechanism for compensating the wave-induced net onshore mass transport in the surf zone. This onshore transport is due to the phase relationship between wave surface elevation and wave orbital velocity (Stokes' drift) and to roller transport (Appendix Eq. 13). Another possible mechanism for compensating wave-induced onshore transport is the occurrence of rip current circulations.

When standing just seaward of the shoreline in the surf zone, one can clearly feel the onshore surface current as a wave crest arrives, and the seaward current near the bottom that occurs beneath the next wave trough.

There is no generally applicable formula for the undertow velocity, as it depends on the particular shoreface morphology. The main driving force for the undertow is the wave set-up at the shoreline. The wave set-up results from the gradient in the net onshore momentum flux (radiation stress) due to wave energy dissipation and from the onshore shear stress produced by the wave bore roller[1][2], as shown in the Appendix (Eq. 12).

Undertow is a major mechanism for beach erosion under storm conditions, see Shoreface profile. The strength of offshore sediment transport under storm condition is due to the strong (more than linear) dependence of the undertow on wave height (Appendix Eqs. 12, 13) and on the high suspended sediment concentrations induced by wave breaking[3].

Related articles

- Wave set-up

- Shoreface profile

- Radiation stress

- Breaker index

- Wave transformation

- Shallow-water wave theory

- Currents

Appendix: Undertow equations

This appendix reproduces the shallow-water equations from which the undertow can be determined. The equations refer to shore-normal wave incidence on a uniform coast (no longshore current). The driving force is a surface wave incident from the far field,

[math]\eta_w (x,t) = \dfrac{H}{2} \cos(\omega t – k x)[/math].

Symbols are defined in Fig. 1,

[math]x=[/math] shore-perpendicular onshore coordinate, [math]z=[/math] vertical upward coordinate, [math]H=[/math] wave height, [math]h=[/math] still water depth, [math]g=[/math] gravitational acceleration, [math]c \approx \sqrt{gh}=[/math] wave celerity, [math]\omega=2 \pi /T = k \, c =[/math] wave radial frequency, [math]k= 2 \pi /L=[/math] wave number, [math]p(x,z,t)=[/math] pressure, [math]\; u(x,z,t), \, w(x,z,t) \,=[/math] horizontal, vertical velocity; [math]\big\langle … \big\rangle \, =[/math] wave-averaged value (averaged over one or more wave cycles, encompassing the turbulence time scale), [math]\; u_0 = \lt u\gt , \, w_0=\lt w\gt [/math], [math]\; u_w, \, w_w \,=[/math] horizontal, vertical wave orbital velocities, [math]\; u', \, w' \, =[/math] turbulent velocity fluctuations.

The velocities [math]u, \, w[/math] and surface elevation [math]\eta[/math] are decomposed as

[math]u = u_0 + u_w+u' \, , \; w = w_0 + w_w +w' \, , \; \eta = \eta_u + \eta_w \, , \; \eta_u = \langle \eta \rangle . \qquad (1)[/math]

The momentum balance equations in the propagation direction and in the vertical direction are

[math]\dfrac{\partial u}{\partial t} + \dfrac{\partial u^2}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w u}{\partial z} + \dfrac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial x} = 0 \, .\qquad (2)[/math]

[math]\dfrac{\partial w}{\partial t} + \dfrac{\partial u w}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w^2}{\partial z} + \dfrac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial p}{\partial z} = -g \, . \qquad (3)[/math]

The continuity equation is [math]\quad \dfrac{\partial u}{\partial x} + \dfrac{\partial w}{\partial z} =0 \, . \quad[/math] The wave motion above the boundary layer is assumed to be irrotational, [math]\quad \dfrac{\partial u}{\partial z} = \dfrac{\partial w}{\partial x} \, . [/math]

From these equations one finds [math]\quad \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} (u_w w_w) = - \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial }{\partial x} (u_w^2 - w_w^2) \; , \quad \dfrac{\partial }{\partial x} (u_w w_w) = \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} (u_w^2 - w_w^2) \, . \qquad (4)[/math]

Substitution in Eqs. (2,3) and averaging over the wave cycle gives

[math]\dfrac{\partial u_0^2}{\partial x} + \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \langle u_w^2 + w_w^2\rangle + \frac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial \langle p \rangle }{\partial x} = - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} \langle u'w' \rangle \, .\qquad (5)[/math]

[math]\frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} \langle u_w^2 + w_w^2 \rangle + \frac{1}{\rho}\dfrac{\partial \langle p \rangle }{\partial z} = -g \, .\qquad (6)[/math]

The pressure [math]\langle p \rangle[/math] is determined by integration of Eq. (6). Differentiation with respect to [math]x[/math] and substitution in Eq. (5) gives

[math]\dfrac{\partial u_0^2}{\partial x} + \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \langle u_w^2(\eta) + w_w^2(\eta) \rangle + g \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} = - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z} \langle u'w' \rangle \, .\qquad (7)[/math]

The term [math]\tau= - \rho \langle u'w' \rangle [/math] represents the turbulent shear stress that diffuses momentum from the net circulation [math]u_0(x,z)[/math] over the vertical. This can represented to a first approximation by a gradient-type diffusion with an eddy-viscosity coefficient [math]K(x,z)[/math],

[math]\tau = \rho \, K(x,z) \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} \, , \qquad (8)[/math]

The net circulation [math]u_0[/math] can now be obtained from the modified Bernoulli equation (7), which is rewritten as

[math] \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z}K(x,z) \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} u_0^2 = \frac{1}{2} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} \langle u_w^2(\eta) + w_w^2(\eta) \rangle + g \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} \, .\qquad (9)[/math]

To solve this equation, the eddy-viscosity coefficient [math]K(x,z)[/math] and the function [math]\partial \langle u_w^2(\eta) + w_w^2(\eta) \rangle / \partial x [/math] must be known. These functions can be determined by numerically solving the Eqs. (2,3) or determined from field or laboratory measurements[4][5].

Approximate analytical expressions have been derived using shallow-water wave theory outside the near-bed wave boundary layer and assuming that bed slope effects can be neglected[1][6][7].

According to shallow-water wave theory, we approximate the wave energy [math]E_w=\rho g H^2 /8[/math] and [math] \langle w^2(\eta) \rangle \lt \lt \langle u^2(\eta) \rangle \approx E_w /(\rho h)[/math]. Assuming that wave energy is mainly lost through depth-induced wave breaking (see Breaker index),

[math]\dfrac{dE_w}{dx} \approx - \dfrac{2 H E_w}{ h c T} \approx - \dfrac{\rho c h}{4 T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3[/math] and [math]\dfrac{d \langle u^2(\eta) \rangle }{dx} \approx \dfrac{1}{\rho h } \dfrac{d E_w}{dx} \approx \dfrac{c}{4 T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 \, . \qquad (10)[/math]

The wave set-up [math]d \eta_u / dx[/math] is related to the radiation stress [math]S_{xx}[/math] resulting from breaker-induced wave dissipation (see Wave set-up),

[math] g \rho d \dfrac{d \eta_u}{dx} = - \dfrac{d}{dx} S_{xx} + \langle \tau_s \rangle - \langle \tau_b \rangle \; , \quad \dfrac{d}{dx} S_{xx} \approx \dfrac{3}{2} \dfrac{dE_w}{dx} \approx -\dfrac{3c}{8T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 \, . \qquad (11)[/math]

The breaker-induced surface shear stress is given by[8] [math]\quad \langle \tau_s \rangle = \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{h} E_r \, , \;[/math] where the roller energy [math]\; E_r \approx \dfrac{\rho A c}{2T} \, \;[/math] and [math]\theta[/math] the roller steepness angle (inclination angle of the bore front).

The water volume [math]A[/math] of the wave bore roller (water volume per longshore meter) is estimated as being close to the square of the bore height.

The approximate analytical undertow equation (9) finally becomes

[math]\quad \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z}K(x,z) \dfrac{\partial u_0}{\partial z} - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x} u_0^2 + \dfrac{\langle \tau_b \rangle }{\rho h} = \dfrac{c}{4T} \Big( \dfrac{H}{h} \Big)^3 + \dfrac{2 \sin \theta }{\rho h^2} E_r \, . \qquad (12)[/math]

Zou et al. (2006[9]) give more elaborate analytical expressions that include the effect of a seabed slope. The bed slope effect appears to be important when comparing results with field observations.

Two boundary conditions are needed to solve the second order differential equation (12). At the seabed, [math]z=-h[/math], the undertow velocity vanishes, [math]u_0(z=-h)=0[/math]. The second condition is the overall mass balance represented by the equation

[math]\int_{-h}^0 u_0(z) dz \approx - \langle (h+\eta)u_w \rangle - \dfrac{A}{T} \approx - \dfrac{c H^2}{8h} - \dfrac{A}{T} \, . \qquad (13)[/math]

This expression includes the mass transport by the roller, representing the roller volume [math]A[/math] which is transported onshore with the wave bore (crest of the broken wave, moving with celerity [math]c[/math]).[1]

A qualitative impression of the undertow velocity profile can be derived from the vertical distribution of the eddy viscosity [math]K(z)[/math]. If the eddy viscosity is assumed uniform over the vertical, the undertow velocity [math]u_0(z)[/math] has a parabolic profile, because the r.h.s. of Eq. (12) does not depend on [math]z[/math] in the analytic model. However, as most turbulence is generated by wave breaking near the water surface, the eddy viscosity is more likely a decreasing function with depth[10]. In this case, the strongest variation of the undertow (greatest gradient) is close to the seabed, as sketched in Fig.1. This undertow profile, with maximum offshore velocity in the lower part of the vertical, best matches observations.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Svendsen, I.A. 1984. Wave heights and set-up in a surf zone. Coast. Eng. 8: 303–329

- ↑ Apotsos, A., Raubenheimer, B., Elgar, S., Guza, R.T. and Smith, J.A. 2007. Effects of wave rollers and bottom stress on wave setup. J. Geophysical Research 112, C02003

- ↑ van der Zanden, J., van der A, D. A., Hurther, D., Caceres, I., O’Donoghue, T. and Ribberink, J. S. 2017. Suspended sediment transport around a large-scale laboratory breaker bar. Coastal Engineering 125: 51–69

- ↑ Stive, M. J. F. and Wind, H.G. 1986. Cross-shore mean flow in the surf zone. Coastal Eng. 10: 325– 340

- ↑ van der Werf, J., Ribberink, J., Kranenburg, W., Neessen, K. and Boers, M. 2017. Contributions to the wave-mean momentum balance in the surf zone. Coastal Engineering 121: 212–220

- ↑ Svendsen, I.A. 1984. Mass flux and undertow in a surf zone. Coast. Eng. 8: 347–365

- ↑ Deigaard, R. and Fredsoe, J. 1989. Shear Stress Distribution in Dissipative Water Waves. Coastal Eng. 13: 357-378

- ↑ Duncan, J.H. 1981. An experimental investigation of breaking waves produced by a towed hydrofoil. Proc. R. Sot. London A, 377: 331-348

- ↑ Zou, Q., Bowen, A.J. and Hay, A.E. 2006. Vertical distribution of wave shear stress in variable water depth: theory and observations. J. Geophys. Res. 111: 1–17

- ↑ Deigaard, R., Justesen, P. and Fredsoe, J. 1991. Modelling of undertow by a one-equation turbulence model. Coast. Eng. 15: 431-458

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|