Difference between revisions of "Waves on a sloping bed"

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) (Created page with " thumb|350px|right|Fig. 1. Non-broken shallow-water wave climbing a sloping shore. This article deals with '''frictionless, non-breaking shallow wat...") |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

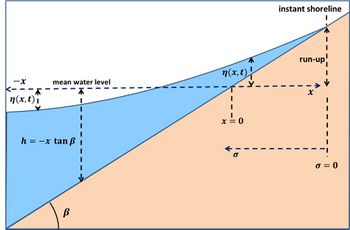

[[File:SlopingBed.jpg|thumb|350px|right|Fig. 1. Non-broken shallow-water wave climbing a sloping shore.]] | [[File:SlopingBed.jpg|thumb|350px|right|Fig. 1. Non-broken shallow-water wave climbing a sloping shore.]] | ||

| Line 5: | Line 4: | ||

This article deals with '''frictionless, non-breaking shallow water waves''' propagating in positive <math>x-</math>direction over a '''sloping bed''' with depth <math>h(x) = - \beta x</math>. | This article deals with '''frictionless, non-breaking shallow water waves''' propagating in positive <math>x-</math>direction over a '''sloping bed''' with depth <math>h(x) = - \beta x</math>. | ||

| − | A mathematical treatment of | + | [[Shallow-water wave theory]] usually considers frictionless nonbreaking waves propagating over a seabed of uniform depth. This yields a reasonable approximation for nonbreaking waves with small wavelengths <math>L</math> propagating on a gently sloping shoreface at some distance from the shoreline, such that <math>Ldh/dx << h</math>. However, this condition generally does not hold for low-frequency waves, such as [[infragravity waves]], [[seiche]]s and [[tsunami]]s, or for waves running up artificial slopes. In these cases, wave propagation theory has to take bed slope into account. Ignoring the effect of bed slope can lead to over- or underestimation of [[wave run-up]] on the beach or [[wave overtopping]] of inclined [[seawall]]s or [[revetments]]. |

| + | |||

| + | A mathematical treatment of frictionless, non-breaking shallow water waves propagating over a sloping bed was developed by Carrier and Greenspan (1957<ref name=CG>Carrier, G. F. and Greenspan, H. P. 1958. Water waves of finite amplitude on a sloping beach. Jour. Fluid Mech. 4: 97-109</ref>). This theory, which is reproduced below, cannot be easily extended to include the effect of frictional dissipation. However, a wave breaking criterion is given, which sets a limit to the applicability of the theory. By respecting this limit, the effect of neglecting frictional wave dissipation is also mitigated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The kinematics of wave uprush on an inclined plane are relevant for processes described in the Coastal Wiki articles [[Infragravity waves]], [[Wave run-up]] , [[Tsunami]], [[Wave overtopping]], [[Swash]] and [[Swash zone dynamics]]. | ||

| Line 48: | Line 51: | ||

We change now to two new independent variables <math>\lambda, \sigma</math> instead of <math>p, q</math> and <math>x, t</math>, | We change now to two new independent variables <math>\lambda, \sigma</math> instead of <math>p, q</math> and <math>x, t</math>, | ||

| − | <math>\lambda = p-q = | + | <math>\lambda = p-q = u+g \beta t \, , \; \sigma = p+q = 2 c = 2 \sqrt{g(\eta - \beta x)} \, . \qquad (9)</math> |

The instant shoreline (water line) is given by <math>\sigma = 0</math>. The variables <math>\sigma, \lambda</math> depend on the wave shape close to the water line. | The instant shoreline (water line) is given by <math>\sigma = 0</math>. The variables <math>\sigma, \lambda</math> depend on the wave shape close to the water line. | ||

| − | Far from the shoreline we have <math>\sigma \approx | + | Far from the shoreline we have <math>\sigma \approx 2 \sqrt{g \beta |x|}</math>. After a time <math>g \beta t >> |u|</math> we have <math>\lambda \approx g \beta t</math>. |

Derivation of Eq. (9) using the chain rule gives | Derivation of Eq. (9) using the chain rule gives | ||

| Line 62: | Line 65: | ||

<math>\sigma \Bigg( \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial \lambda^2}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial \sigma^2}\normalsize \Bigg) – 3 \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize =0 \, . \qquad (11)</math> | <math>\sigma \Bigg( \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial \lambda^2}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial \sigma^2}\normalsize \Bigg) – 3 \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize =0 \, . \qquad (11)</math> | ||

| − | Because <math>g \beta t = - u + \lambda | + | Because <math>g \beta t = - u + \lambda </math>, Eq. (11) also holds for the velocity <math>u(\sigma, \lambda)</math>. A solution of Eq. (11) can be found when writing the velocity in the form |

<math>u(\sigma, \lambda) \equiv \Large\frac{1}{\sigma}\frac{\partial \phi(\sigma,\lambda)}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, . \qquad (12)</math> | <math>u(\sigma, \lambda) \equiv \Large\frac{1}{\sigma}\frac{\partial \phi(\sigma,\lambda)}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, . \qquad (12)</math> | ||

| Line 80: | Line 83: | ||

The solution is further defined by the initial (<math>t=0</math>) wave surface elevation <math>\eta(x,0)</math> from the instant shoreline <math>\sigma =0</math> to <math>\sigma = \infty</math>. The fluid is assumed to be initially at rest: <math>\lambda=0, \; u=0</math>. As the wave motion is assumed frictionless, no boundary forcing is needed to keep the wave motion going. However, if the initial surface oscillation does not extend to infinity, the wave motion near the shoreline will eventually come to rest. | The solution is further defined by the initial (<math>t=0</math>) wave surface elevation <math>\eta(x,0)</math> from the instant shoreline <math>\sigma =0</math> to <math>\sigma = \infty</math>. The fluid is assumed to be initially at rest: <math>\lambda=0, \; u=0</math>. As the wave motion is assumed frictionless, no boundary forcing is needed to keep the wave motion going. However, if the initial surface oscillation does not extend to infinity, the wave motion near the shoreline will eventually come to rest. | ||

| − | From the initial wave surface elevation it is possible to compute the derivative <math>\partial u / \partial \lambda \equiv f(\sigma)</math> at <math>\lambda=0</math>. First the derivative <math>\partial x / \partial \sigma</math> has to be determined. This can be done by solving Eq. (9) at <math>t = 0</math> to determine the function <math>x(\sigma, \lambda=0)</math> and the derivative <math>\partial x / \partial \sigma</math>. The equation <math>\; \sigma = | + | From the initial wave surface elevation it is possible to compute the derivative <math>\partial u / \partial \lambda \equiv f(\sigma)</math> at <math>\lambda=0</math>. First the derivative <math>\partial x / \partial \sigma</math> has to be determined. This can be done by solving Eq. (9) at <math>t = 0</math> to determine the function <math>x(\sigma, \lambda=0)</math> and the derivative <math>\partial x / \partial \sigma</math>. The equation <math>\; \sigma = 2 \sqrt{g(\eta(x,0) - \beta x)} </math> can for some particular functions <math>\eta(x,0)</math> be solved analytically, but in general only a numerical solution can be obtained. |

Using successively Eqs. (9, 4, 5, 10) and <math>u=0</math> we have | Using successively Eqs. (9, 4, 5, 10) and <math>u=0</math> we have | ||

| Line 86: | Line 89: | ||

<math>\Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p} \frac{\partial p}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\frac{\partial q}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \Big( \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\normalsize \Big) = \large\frac{1}{2} c \, \Big( - \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize \Big) = - c \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize . </math> | <math>\Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p} \frac{\partial p}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\frac{\partial q}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \Big( \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\normalsize \Big) = \large\frac{1}{2} c \, \Big( - \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize \Big) = - c \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize . </math> | ||

| − | From Eq. (9) we have <math>f(\sigma) \equiv \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = | + | From Eq. (9) we have <math>f(\sigma) \equiv \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = 1 – g \beta \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = 1 + \Large\frac{2 g \beta}{\sigma}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, . \qquad (15) </math> |

Carrier and Greenspan (1957<ref name=CG>Carrier, G. F. and Greenspan, H. P. 1958. Water waves of finite amplitude on a sloping beach. Jour. Fluid Mech. 4: 97-109</ref>) derived the following expression relating the velocity field <math>u(\sigma, \lambda)</math> to the initial condition <math>\partial u / \partial \lambda \equiv f(\sigma)</math> at <math>\lambda=0</math>: | Carrier and Greenspan (1957<ref name=CG>Carrier, G. F. and Greenspan, H. P. 1958. Water waves of finite amplitude on a sloping beach. Jour. Fluid Mech. 4: 97-109</ref>) derived the following expression relating the velocity field <math>u(\sigma, \lambda)</math> to the initial condition <math>\partial u / \partial \lambda \equiv f(\sigma)</math> at <math>\lambda=0</math>: | ||

| Line 100: | Line 103: | ||

Using Eqs. (4, 5, 9) we find for <math>t > 0</math> | Using Eqs. (4, 5, 9) we find for <math>t > 0</math> | ||

| − | <math>\Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = u \,\Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize - c \, \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = \Large\frac{1}{g \beta}\normalsize \Bigg( - u \, \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize - \Large\frac{1}{ | + | <math>\Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = u \,\Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize - c \, \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = \Large\frac{1}{g \beta}\normalsize \Bigg( - u \, \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize - \Large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \sigma + \Large\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial^2 \phi}{\partial \lambda \partial \sigma}\normalsize \Bigg) \, . </math> |

The wave elevation <math>\eta</math> and the coordinates <math>x, t</math> can now determined from | The wave elevation <math>\eta</math> and the coordinates <math>x, t</math> can now determined from | ||

| − | <math>x = \Large\frac{1}{g \beta}\normalsize \Bigg( - | + | <math>x = \Large\frac{1}{2 g \beta}\normalsize \Bigg( - u^2 - \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \sigma^2 + \Large\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize \Bigg) \, , \qquad (18)</math> |

| − | <math>t = \Large\frac{1}{ | + | <math>t = \Large\frac{1}{g \beta}\normalsize ( \lambda – u ) \, , \qquad (19)</math> |

| − | <math>\eta = \Large\frac{c^2}{g}\normalsize + \beta x = \Large\frac{1}{ | + | <math>\eta = \Large\frac{c^2}{g}\normalsize + \beta x = \Large\frac{1}{2g}\normalsize \Bigg( - u^2 + \Large\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize \Bigg) \, . \qquad (20)</math> |

From a few examples with initial wave shapes that allow an analytical solution of the equations (15) and (16), Carrier and Greenspan (1957<ref name=CG>Carrier, G. F. and Greenspan, H. P. 1958. Water waves of finite amplitude on a sloping beach. Jour. Fluid Mech. 4: 97-109</ref>) showed that the wave run-up at the shoreline is higher than the maximum initial wave amplitude. | From a few examples with initial wave shapes that allow an analytical solution of the equations (15) and (16), Carrier and Greenspan (1957<ref name=CG>Carrier, G. F. and Greenspan, H. P. 1958. Water waves of finite amplitude on a sloping beach. Jour. Fluid Mech. 4: 97-109</ref>) showed that the wave run-up at the shoreline is higher than the maximum initial wave amplitude. | ||

| − | The wave amplitude given by equations (17) and (20) vanishes at large distances from the shoreline. Due to the uniform slope of the bed, there is no limit to the depth increase, which is physically unrealistic. The practical relevance of the theory is therefore limited to a region close to the shoreline. At larger distances, a wave boundary condition must be applied. The mathematical treatment of the nonlinear problem is very complex. | + | The wave amplitude given by equations (17) and (20) vanishes at large distances from the shoreline. Due to the uniform slope of the bed, there is no limit to the depth increase, which is physically unrealistic. The practical relevance of the theory is therefore limited to a region close to the shoreline. At larger distances, a wave boundary condition must be applied. The mathematical treatment of the wave boundary condition for the nonlinear problem is very complex (see, for example, Rybkin et al. (2021<ref>Rybkin, A., Nicolsky, D., Pelinovsky, E. and Buckel, M. 2021. The Generalized Carrier–Greenspan Transform for the Shallow Water System with Arbitrary Initial and Boundary Conditions. Water Waves 3: 267–296</ref>). However, useful expressions can be obtained in the linear case discussed below. |

==Linear wave equations== | ==Linear wave equations== | ||

| Line 122: | Line 125: | ||

The solution of these equations can be found with a similar transformation of the independent variables as for the nonlinear case, but retaining only the first order linear terms,<ref name=MP>Massel, S.R. and Pelinovski, E.N. 2001. Run-up of dispersive and breaking waves on beaches. Oceanologia 43: 61-97</ref> | The solution of these equations can be found with a similar transformation of the independent variables as for the nonlinear case, but retaining only the first order linear terms,<ref name=MP>Massel, S.R. and Pelinovski, E.N. 2001. Run-up of dispersive and breaking waves on beaches. Oceanologia 43: 61-97</ref> | ||

| − | <math>\lambda_0 = | + | <math>\lambda_0 = g \beta t \, , \; \sigma_0 = 2 c = 2 \sqrt{- g \beta x} \, . \qquad (22)</math> |

The old variables are now related to the new variables by the expressions | The old variables are now related to the new variables by the expressions | ||

| − | <math>\eta = \Large\frac{1}{ | + | <math>\eta = \Large\frac{1}{2g}\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \lambda_0}\normalsize \, , \quad |

| − | x = - \Large\frac{\sigma_0^2 }{ | + | x = - \Large\frac{\sigma_0^2 }{4g \beta}\normalsize \, , \quad t = \Large\frac{\lambda_0}{g \beta}\normalsize \, .\qquad (23)</math> |

The wave orbital velocity is related to the velocity potential <math>\phi_0</math> according to equation (12), | The wave orbital velocity is related to the velocity potential <math>\phi_0</math> according to equation (12), | ||

| Line 141: | Line 144: | ||

<math>\phi_0 (\lambda_0, \sigma_0) = A_0 \, J_0( \chi \sigma_0) \, \cos (\chi \lambda_0 -\psi) \, . \qquad (26)</math> | <math>\phi_0 (\lambda_0, \sigma_0) = A_0 \, J_0( \chi \sigma_0) \, \cos (\chi \lambda_0 -\psi) \, . \qquad (26)</math> | ||

| − | The linear solution can be readily expressed as a function of the original variables <math>x, t</math>, for arbitrary <math>A_0, \psi</math>. Considering a standing sinusoidal wave with angular frequency <math>\omega</math>, we have | + | The linear solution can be readily expressed as a function of the original variables <math>x, t</math>, for arbitrary <math>A_0, \psi</math>. Considering a standing sinusoidal wave with angular frequency <math>\omega = 2 \pi /T</math>, we have |

| − | <math>\eta(x,t) = \Large\frac{1}{ | + | <math>\eta(x,t) = \Large\frac{1}{2 g}\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \lambda_0}\normalsize = \eta_{max} \, J_0( \large\frac{\omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{-g \beta x}) \, \sin (\omega t -\psi) \, , \quad u(x,t) = \Large\frac{1}{\sigma_0}\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \sigma_0}\normalsize = \Large\frac{g \eta_{max}}{\sqrt{-g \beta x}}\normalsize J_1( \large\frac{2 \omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{-g \beta x}) \, \cos (\omega t -\psi) \,. \qquad (26)</math> |

| − | The | + | The solutions for the linear and nonlinear cases are identical for large values of <math>x</math> and <math>t</math>. At <math>x=0</math>, the amplitude of the linear wave corresponds to the amplitude of the nonlinear wave (same initial conditions) at <math>\sigma=0</math> <ref name=MP>Massel, S.R. and Pelinovski, E.N. 2001. Run-up of dispersive and breaking waves on beaches. Oceanologia 43: 61-97</ref>. For low-frequency waves on steep shores one may approximate <math>J_0(\large\frac{2 \omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{-g \eta_{max}}) \approx 1</math>. Thus for the linear case, <math>\eta_{max}</math> equals half the run-up <math>R</math> and the maximum shoreline advance <math>x_R</math> can be determined by <math>x_R = \eta_{max} / \beta</math>. |

| − | In real situations, at some distance from the shoreline | + | In real situations, the bed slope will decrease at some distance from the shoreline and eventually become very small. In this case a boundary condition must be applied at the seaward boundary of the sloping nearshore zone. Let <math>h_0 = -\beta x_0</math> be the depth of the offshore area and let <math>H_0</math> be the height of the standing wave at the boundary <math>x = -x_0</math>. If <math>y = \large\frac{2 \omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{g h_0} >>1</math>, the Bessel function can be approximated by <math>J_0(y) \approx \sqrt{\large\frac{2}{\pi y}\normalsize} \cos(y - \large\frac{\pi}{4}\normalsize) .</math> Substitution in the expression (26) gives |

| − | == | + | <math>R = 2 \eta_{max} = H_0 \Big( \Large\frac{\pi}{\beta}\normalsize \Big)^{1/2} \Big( \Large\frac{h_0 \omega^2}{g}\normalsize \Big)^{1/4} \, , \qquad (27)</math> |

| + | |||

| + | The maximum velocity <math>V</math> occurs at <math>x=0</math> and is given by | ||

| − | + | <math>V = u_{max} = \omega H_0 \Big( \Large\frac{\pi }{4 \beta^3 }\normalsize \Big)^{1/2} \Big( \Large\frac{h_0 \omega^2}{g}\normalsize \Big)^{1/4} \, . \qquad (28)</math> | |

| − | <math> | + | The solution (26) represents a standing wave (sum of incoming and reflected waves) and <math>H_0</math> is twice the standing wave amplitude at <math>x=-x_0</math>. The run-up <math>R</math> decreases with increasing slope <math>\beta</math> and increases with increasing depth <math>h_0</math>, i.e. with increasing length <math>|x_0|</math> of the sloping bed. However, for long slopes, wave dissipation cannot be ignored, thus moderating the increase in run-up. |

| − | + | ==Wave breaking== | |

| − | <math> | + | The transformation of <math>x, t </math> to <math>\sigma, \lambda</math> variables must be single-valued, which is equivalent to the condition that no wave breaking will occur<ref name=CG/>. This is the case if the Jacobian <math>|J| = \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = \large\frac{\sigma}{2}\normalsize \Bigg| \big( \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \big)^2 - \big( \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize \big)^2 \Bigg| \neq 0 \, . \qquad (29)</math>. |

| − | + | For the linear case, Eq.(26), this condition is met if the wave amplitude at the shoreline <math>\quad \eta_{max} < \eta_{max}^{br} = \Large\frac{g \beta^2}{\omega^2}\normalsize \, . \qquad (30)</math> | |

| − | <math> | + | This condition can be related to the offshore wave height <math>H_0</math> (incident wave) by using the expression (27), |

| − | + | <math>H_0 < H_0^{br} = \Large\frac{h_0}{2 \sqrt{\pi}} \Big( \frac{g \beta^2}{h_0 \omega^2}\normalsize \Big)^{5/4} \, . \qquad (31)</math> | |

| − | <math>\ | + | This condition implies that short waves (period <math>T =2 \pi / \omega \sim 10 \, s</math>) may break on sandy beaches (<math>\beta \sim 0.03</math>) if offshore wave heights are larger than a centimeter. For wave heights on the order of 0.5 m, non-breaking conditions may occur for [[infragravity waves]] (<math>T > 100 \, s</math>) on sandy beaches (<math>\beta \sim 0.03</math>) or for short waves (<math>T \sim 10 \, s</math>) on steep slopes (<math>\beta > 0.3</math>). |

| − | + | The condition (29) can be compared to the nonbreaking wave-surge criterion for the [[surf similarity parameter]] according to Battjes (1974<ref>Battjes, J.A. 1974. Surf similarity. Proceedings 14th International Conference on Coastal Engineering, pp. 466–480</ref>), | |

| − | + | <math>\xi > \xi_{br} = \beta \Big( \Large\frac{L_0}{ H_0^{br}}\normalsize \Big)^{1/2} \approx 3.3 \,, \quad </math> giving <math>\quad H_0 < H_0^{br} \approx 0. 2 \pi h_0 \Big( \Large\frac{g \beta^2}{h_0 \omega^2}\normalsize \Big) \, . \qquad (32)</math> | |

| + | The two criteria (31) and (32) are similar. However, criterium (31) is more severe than criterium (32). Field observations suggest that wave breaking occurs for values of <math>\eta_{max}</math> which are a few times larger than the limit (30) <ref>Hughes, M.G., Baldock, T.E. and Aagaard, T. 2017. Swash saturation: is it universal and do we have an appropriate model? Coastal Dynamics Conf. 2017, Paper No.108, pp. 192-203</ref>. This implies a similar raise of the corresponding offshore wave height limit (31) and better agreement with the criterion (32). | ||

| Line 178: | Line 184: | ||

:[[Tsunami]] | :[[Tsunami]] | ||

:[[Breaker index]] | :[[Breaker index]] | ||

| + | :[[Swash]] | ||

| + | :[[Swash zone dynamics]] | ||

| + | :[[Shallow-water wave theory]] | ||

| + | |||

Latest revision as of 16:48, 11 January 2025

This article deals with frictionless, non-breaking shallow water waves propagating in positive [math]x-[/math]direction over a sloping bed with depth [math]h(x) = - \beta x[/math].

Shallow-water wave theory usually considers frictionless nonbreaking waves propagating over a seabed of uniform depth. This yields a reasonable approximation for nonbreaking waves with small wavelengths [math]L[/math] propagating on a gently sloping shoreface at some distance from the shoreline, such that [math]Ldh/dx \lt \lt h[/math]. However, this condition generally does not hold for low-frequency waves, such as infragravity waves, seiches and tsunamis, or for waves running up artificial slopes. In these cases, wave propagation theory has to take bed slope into account. Ignoring the effect of bed slope can lead to over- or underestimation of wave run-up on the beach or wave overtopping of inclined seawalls or revetments.

A mathematical treatment of frictionless, non-breaking shallow water waves propagating over a sloping bed was developed by Carrier and Greenspan (1957[1]). This theory, which is reproduced below, cannot be easily extended to include the effect of frictional dissipation. However, a wave breaking criterion is given, which sets a limit to the applicability of the theory. By respecting this limit, the effect of neglecting frictional wave dissipation is also mitigated.

The kinematics of wave uprush on an inclined plane are relevant for processes described in the Coastal Wiki articles Infragravity waves, Wave run-up , Tsunami, Wave overtopping, Swash and Swash zone dynamics.

Contents

Characteristic wave equations

The wave equations read:

[math]\Large\frac{\partial \eta}{\partial t}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial (h +\eta) u }{\partial x}\normalsize = 0 \; , \quad \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\normalsize + u \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\normalsize + g \Large\frac{\partial \eta}{\partial x}\normalsize = 0\, . \qquad (1)[/math]

Here is (Fig. 1): [math]\; \eta(x,t)=[/math]wave surface elevation, [math]u(x,t)=[/math]wave orbital velocity, [math]g=[/math]gravitational circulation, [math]\beta \approx \tan \beta =[/math]bed slope, [math]t=[/math]time coordinate.

These equations describe two characteristics waves

[math]p(x,t) = u + 2 c + g \beta t \, , \quad q(x,t) = u - 2 c + g \beta t \,, \quad c = \sqrt{g(\eta + h)} = \sqrt{g(\eta - \beta x)} \qquad (2)[/math]

propagating along characteristic curves, according to the characteristic equations

[math]\Large\frac{dp}{dt}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial p}{\partial t}\normalsize + \Large\frac{dx}{dt}\frac{\partial p}{\partial x}\normalsize =0 \, , \; \Large\frac{dx}{dt}\normalsize = u+c \, ; \quad \Large\frac{dq}{dt}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial q}{\partial t}\normalsize + \Large\frac{dx}{dt}\frac{\partial q}{\partial x}\normalsize =0 \, , \; \Large\frac{dx}{dt}\normalsize = u-c \, .\qquad (3)[/math]

It can be verified that Eqs. (2, 3) are equivalent to Eq. (1).

Considering [math]p[/math] and [math]q[/math] as new independent variables we can write the characteristic waves as

[math]\Large\frac{\partial p}{\partial q}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial }{\partial q}\normalsize (u+2c+g \beta t) = 0 \, , \quad \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\normalsize = (u+c) \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize \, , \qquad (4)[/math]

[math]\Large\frac{\partial q}{\partial p}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial }{\partial p}\normalsize (u-2c+g \beta t) =0 \, , \quad \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p}\normalsize = (u-c) \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize \, . \qquad (5)[/math]

We eliminate [math]x[/math] by cross-differentiation the r.h.s. of Eqs. (4, 5), giving

[math]\Large\frac{\partial (u+c)}{\partial p}\normalsize \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize + c \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial pq}\normalsize =\Large\frac{\partial (u-c)}{\partial q}\normalsize \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize - c \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial pq}\normalsize \, . \qquad (6) [/math]

From the l.h.s. of Eqs. (4,5) we have

[math]\Large\frac{\partial (u+c)}{\partial p}\normalsize = 3 \Large\frac{\partial c}{\partial p}\normalsize - g \beta \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize \, , \quad \Large\frac{\partial (u-c)}{\partial q}\normalsize = - 3 \Large\frac{\partial c}{\partial q}\normalsize - g \beta \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize \, . \quad (7)[/math]

Combining Eqs. (6, 7) gives

[math]2 c \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial pq}\normalsize = - 3 \Bigg( \Large\frac{\partial c}{\partial p}\normalsize \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial c}{\partial q}\normalsize \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize \Bigg) \,. \qquad (8)[/math]

Solution of the nonlinear wave equations

We change now to two new independent variables [math]\lambda, \sigma[/math] instead of [math]p, q[/math] and [math]x, t[/math],

[math]\lambda = p-q = u+g \beta t \, , \; \sigma = p+q = 2 c = 2 \sqrt{g(\eta - \beta x)} \, . \qquad (9)[/math]

The instant shoreline (water line) is given by [math]\sigma = 0[/math]. The variables [math]\sigma, \lambda[/math] depend on the wave shape close to the water line.

Far from the shoreline we have [math]\sigma \approx 2 \sqrt{g \beta |x|}[/math]. After a time [math]g \beta t \gt \gt |u|[/math] we have [math]\lambda \approx g \beta t[/math].

Derivation of Eq. (9) using the chain rule gives

[math]\Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize +\Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, , \; \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize = - \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, . \qquad (10)[/math]

Substitution in Eq. (8) gives

[math]\sigma \Bigg( \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial \lambda^2}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial^2 t}{\partial \sigma^2}\normalsize \Bigg) – 3 \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize =0 \, . \qquad (11)[/math]

Because [math]g \beta t = - u + \lambda [/math], Eq. (11) also holds for the velocity [math]u(\sigma, \lambda)[/math]. A solution of Eq. (11) can be found when writing the velocity in the form

[math]u(\sigma, \lambda) \equiv \Large\frac{1}{\sigma}\frac{\partial \phi(\sigma,\lambda)}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, . \qquad (12)[/math]

Substitution of this expression for [math]t[/math] in Eq. (11) gives

[math] \Large\frac{\partial}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \Big( \sigma \Large\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \Big) - \sigma \Large\frac{\partial^2 \phi}{\partial \lambda^2}\normalsize =0 \, . \qquad (13)[/math]

It can easily be verified that a solution of this equation is given by

[math]\phi (\lambda, \sigma) = A \, J_0( \chi \sigma) \, \cos (\chi \lambda -\psi) \, , \qquad (14)[/math]

where [math]A, \chi, \psi[/math] are arbitrary constants and [math]J_0[/math] is a Bessel function of the first kind. This is not a simple expression because [math]\lambda[/math] and [math]\sigma[/math] depend on the solution [math]u, \eta \,[/math] according to Eq. (9).

Boundary conditions

The solution is further defined by the initial ([math]t=0[/math]) wave surface elevation [math]\eta(x,0)[/math] from the instant shoreline [math]\sigma =0[/math] to [math]\sigma = \infty[/math]. The fluid is assumed to be initially at rest: [math]\lambda=0, \; u=0[/math]. As the wave motion is assumed frictionless, no boundary forcing is needed to keep the wave motion going. However, if the initial surface oscillation does not extend to infinity, the wave motion near the shoreline will eventually come to rest.

From the initial wave surface elevation it is possible to compute the derivative [math]\partial u / \partial \lambda \equiv f(\sigma)[/math] at [math]\lambda=0[/math]. First the derivative [math]\partial x / \partial \sigma[/math] has to be determined. This can be done by solving Eq. (9) at [math]t = 0[/math] to determine the function [math]x(\sigma, \lambda=0)[/math] and the derivative [math]\partial x / \partial \sigma[/math]. The equation [math]\; \sigma = 2 \sqrt{g(\eta(x,0) - \beta x)} [/math] can for some particular functions [math]\eta(x,0)[/math] be solved analytically, but in general only a numerical solution can be obtained.

Using successively Eqs. (9, 4, 5, 10) and [math]u=0[/math] we have

[math]\Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p} \frac{\partial p}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\frac{\partial q}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \Big( \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial p}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial q}\normalsize \Big) = \large\frac{1}{2} c \, \Big( - \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial p}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial q}\normalsize \Big) = - c \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize . [/math]

From Eq. (9) we have [math]f(\sigma) \equiv \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = 1 – g \beta \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = 1 + \Large\frac{2 g \beta}{\sigma}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \, . \qquad (15) [/math]

Carrier and Greenspan (1957[1]) derived the following expression relating the velocity field [math]u(\sigma, \lambda)[/math] to the initial condition [math]\partial u / \partial \lambda \equiv f(\sigma)[/math] at [math]\lambda=0[/math]:

[math]u (\sigma, \lambda) = \Large\frac{1}{\sigma}\normalsize \int_0^{\infty} d\chi J_1(\chi \sigma) \sin \chi \lambda \int_0^{\infty} d\sigma' \sigma'^2 J_1(\chi \sigma') f(\sigma') \, , \qquad (16) [/math]

where [math]J_1[/math] is a Bessel function of the first kind.

The potential [math]\phi[/math] (Eq. (12)) is given by

[math]\phi (\sigma, \lambda) = - \int_0^{\infty} d\chi J_0(\chi \sigma) \Large\frac{\sin \chi \lambda }{\chi}\normalsize \int_0^{\infty} d\sigma' \sigma'^2 J_1(\chi \sigma') f(\sigma') \, . \qquad (17) [/math]

Using Eqs. (4, 5, 9) we find for [math]t \gt 0[/math]

[math]\Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize = u \,\Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize - c \, \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = \Large\frac{1}{g \beta}\normalsize \Bigg( - u \, \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize - \Large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \sigma + \Large\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial^2 \phi}{\partial \lambda \partial \sigma}\normalsize \Bigg) \, . [/math]

The wave elevation [math]\eta[/math] and the coordinates [math]x, t[/math] can now determined from

[math]x = \Large\frac{1}{2 g \beta}\normalsize \Bigg( - u^2 - \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \sigma^2 + \Large\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize \Bigg) \, , \qquad (18)[/math]

[math]t = \Large\frac{1}{g \beta}\normalsize ( \lambda – u ) \, , \qquad (19)[/math]

[math]\eta = \Large\frac{c^2}{g}\normalsize + \beta x = \Large\frac{1}{2g}\normalsize \Bigg( - u^2 + \Large\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize \Bigg) \, . \qquad (20)[/math]

From a few examples with initial wave shapes that allow an analytical solution of the equations (15) and (16), Carrier and Greenspan (1957[1]) showed that the wave run-up at the shoreline is higher than the maximum initial wave amplitude.

The wave amplitude given by equations (17) and (20) vanishes at large distances from the shoreline. Due to the uniform slope of the bed, there is no limit to the depth increase, which is physically unrealistic. The practical relevance of the theory is therefore limited to a region close to the shoreline. At larger distances, a wave boundary condition must be applied. The mathematical treatment of the wave boundary condition for the nonlinear problem is very complex (see, for example, Rybkin et al. (2021[2]). However, useful expressions can be obtained in the linear case discussed below.

Linear wave equations

The linear wave equations read

[math]\Large\frac{\partial \eta}{\partial t}\normalsize + \Large\frac{\partial (hu)}{\partial x}\normalsize = 0 \; , \quad \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\normalsize + g \Large\frac{\partial \eta}{\partial x}\normalsize = 0\, . \qquad (21)[/math]

The solution of these equations can be found with a similar transformation of the independent variables as for the nonlinear case, but retaining only the first order linear terms,[3]

[math]\lambda_0 = g \beta t \, , \; \sigma_0 = 2 c = 2 \sqrt{- g \beta x} \, . \qquad (22)[/math]

The old variables are now related to the new variables by the expressions

[math]\eta = \Large\frac{1}{2g}\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \lambda_0}\normalsize \, , \quad x = - \Large\frac{\sigma_0^2 }{4g \beta}\normalsize \, , \quad t = \Large\frac{\lambda_0}{g \beta}\normalsize \, .\qquad (23)[/math]

The wave orbital velocity is related to the velocity potential [math]\phi_0[/math] according to equation (12),

[math]u(\sigma_0, \lambda_0) = \Large\frac{1}{\sigma_0}\frac{\partial \phi_0(\sigma_0,\lambda_0)}{\partial \sigma_0}\normalsize \, , \qquad (24)[/math]

which satisfies the linear differential equation (11),

[math] \Large\frac{\partial}{\partial \sigma_0}\normalsize \Big( \sigma_0 \Large\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \sigma_0}\normalsize \Big) - \sigma_0 \Large\frac{\partial^2 \phi_0}{\partial \lambda_0^2}\normalsize =0 \, . \qquad (25)[/math]

It can easily be verified that the expressions (23-25) solve the linear equations (21). The solution is the same expression (14) as for the nonlinear case,

[math]\phi_0 (\lambda_0, \sigma_0) = A_0 \, J_0( \chi \sigma_0) \, \cos (\chi \lambda_0 -\psi) \, . \qquad (26)[/math]

The linear solution can be readily expressed as a function of the original variables [math]x, t[/math], for arbitrary [math]A_0, \psi[/math]. Considering a standing sinusoidal wave with angular frequency [math]\omega = 2 \pi /T[/math], we have

[math]\eta(x,t) = \Large\frac{1}{2 g}\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \lambda_0}\normalsize = \eta_{max} \, J_0( \large\frac{\omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{-g \beta x}) \, \sin (\omega t -\psi) \, , \quad u(x,t) = \Large\frac{1}{\sigma_0}\frac{\partial \phi_0}{\partial \sigma_0}\normalsize = \Large\frac{g \eta_{max}}{\sqrt{-g \beta x}}\normalsize J_1( \large\frac{2 \omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{-g \beta x}) \, \cos (\omega t -\psi) \,. \qquad (26)[/math]

The solutions for the linear and nonlinear cases are identical for large values of [math]x[/math] and [math]t[/math]. At [math]x=0[/math], the amplitude of the linear wave corresponds to the amplitude of the nonlinear wave (same initial conditions) at [math]\sigma=0[/math] [3]. For low-frequency waves on steep shores one may approximate [math]J_0(\large\frac{2 \omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{-g \eta_{max}}) \approx 1[/math]. Thus for the linear case, [math]\eta_{max}[/math] equals half the run-up [math]R[/math] and the maximum shoreline advance [math]x_R[/math] can be determined by [math]x_R = \eta_{max} / \beta[/math].

In real situations, the bed slope will decrease at some distance from the shoreline and eventually become very small. In this case a boundary condition must be applied at the seaward boundary of the sloping nearshore zone. Let [math]h_0 = -\beta x_0[/math] be the depth of the offshore area and let [math]H_0[/math] be the height of the standing wave at the boundary [math]x = -x_0[/math]. If [math]y = \large\frac{2 \omega}{g \beta}\normalsize \sqrt{g h_0} \gt \gt 1[/math], the Bessel function can be approximated by [math]J_0(y) \approx \sqrt{\large\frac{2}{\pi y}\normalsize} \cos(y - \large\frac{\pi}{4}\normalsize) .[/math] Substitution in the expression (26) gives

[math]R = 2 \eta_{max} = H_0 \Big( \Large\frac{\pi}{\beta}\normalsize \Big)^{1/2} \Big( \Large\frac{h_0 \omega^2}{g}\normalsize \Big)^{1/4} \, , \qquad (27)[/math]

The maximum velocity [math]V[/math] occurs at [math]x=0[/math] and is given by

[math]V = u_{max} = \omega H_0 \Big( \Large\frac{\pi }{4 \beta^3 }\normalsize \Big)^{1/2} \Big( \Large\frac{h_0 \omega^2}{g}\normalsize \Big)^{1/4} \, . \qquad (28)[/math]

The solution (26) represents a standing wave (sum of incoming and reflected waves) and [math]H_0[/math] is twice the standing wave amplitude at [math]x=-x_0[/math]. The run-up [math]R[/math] decreases with increasing slope [math]\beta[/math] and increases with increasing depth [math]h_0[/math], i.e. with increasing length [math]|x_0|[/math] of the sloping bed. However, for long slopes, wave dissipation cannot be ignored, thus moderating the increase in run-up.

Wave breaking

The transformation of [math]x, t [/math] to [math]\sigma, \lambda[/math] variables must be single-valued, which is equivalent to the condition that no wave breaking will occur[1]. This is the case if the Jacobian [math]|J| = \Large\frac{\partial x}{\partial \sigma}\frac{\partial t}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial t}{\partial \sigma}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize = \large\frac{\sigma}{2}\normalsize \Bigg| \big( \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \sigma}\normalsize \big)^2 - \big( \large\frac{1}{2}\normalsize - \Large\frac{\partial u}{\partial \lambda}\normalsize \big)^2 \Bigg| \neq 0 \, . \qquad (29)[/math].

For the linear case, Eq.(26), this condition is met if the wave amplitude at the shoreline [math]\quad \eta_{max} \lt \eta_{max}^{br} = \Large\frac{g \beta^2}{\omega^2}\normalsize \, . \qquad (30)[/math]

This condition can be related to the offshore wave height [math]H_0[/math] (incident wave) by using the expression (27),

[math]H_0 \lt H_0^{br} = \Large\frac{h_0}{2 \sqrt{\pi}} \Big( \frac{g \beta^2}{h_0 \omega^2}\normalsize \Big)^{5/4} \, . \qquad (31)[/math]

This condition implies that short waves (period [math]T =2 \pi / \omega \sim 10 \, s[/math]) may break on sandy beaches ([math]\beta \sim 0.03[/math]) if offshore wave heights are larger than a centimeter. For wave heights on the order of 0.5 m, non-breaking conditions may occur for infragravity waves ([math]T \gt 100 \, s[/math]) on sandy beaches ([math]\beta \sim 0.03[/math]) or for short waves ([math]T \sim 10 \, s[/math]) on steep slopes ([math]\beta \gt 0.3[/math]).

The condition (29) can be compared to the nonbreaking wave-surge criterion for the surf similarity parameter according to Battjes (1974[4]),

[math]\xi \gt \xi_{br} = \beta \Big( \Large\frac{L_0}{ H_0^{br}}\normalsize \Big)^{1/2} \approx 3.3 \,, \quad [/math] giving [math]\quad H_0 \lt H_0^{br} \approx 0. 2 \pi h_0 \Big( \Large\frac{g \beta^2}{h_0 \omega^2}\normalsize \Big) \, . \qquad (32)[/math]

The two criteria (31) and (32) are similar. However, criterium (31) is more severe than criterium (32). Field observations suggest that wave breaking occurs for values of [math]\eta_{max}[/math] which are a few times larger than the limit (30) [5]. This implies a similar raise of the corresponding offshore wave height limit (31) and better agreement with the criterion (32).

Related articles

- Wave run-up

- Dam break flow

- Tsunami

- Breaker index

- Swash

- Swash zone dynamics

- Shallow-water wave theory

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Carrier, G. F. and Greenspan, H. P. 1958. Water waves of finite amplitude on a sloping beach. Jour. Fluid Mech. 4: 97-109

- ↑ Rybkin, A., Nicolsky, D., Pelinovsky, E. and Buckel, M. 2021. The Generalized Carrier–Greenspan Transform for the Shallow Water System with Arbitrary Initial and Boundary Conditions. Water Waves 3: 267–296

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Massel, S.R. and Pelinovski, E.N. 2001. Run-up of dispersive and breaking waves on beaches. Oceanologia 43: 61-97

- ↑ Battjes, J.A. 1974. Surf similarity. Proceedings 14th International Conference on Coastal Engineering, pp. 466–480

- ↑ Hughes, M.G., Baldock, T.E. and Aagaard, T. 2017. Swash saturation: is it universal and do we have an appropriate model? Coastal Dynamics Conf. 2017, Paper No.108, pp. 192-203

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|