Ocean and shelf tides

In this article the term tide refers to the astronomical tide, unless stated otherwise.

Contents

Introduction

Tidal motion is the oscillation of ocean waters under the influence of the attractive gravitational forces of the moon and the sun. The response of the ocean to the gravitational forces follows a pattern of rotating ('amphidromic') systems, as a consequence of earth's rotation. The frequencies are determined by the cycles in the motions of moon, sun and earth. The amplitude of the tidal oscillations is very small compared to ocean depths. The ocean tidal oscillation in each point can therefore be represented by a linear superposition of sinusoidal tidal components with periods derived from the various astronomical cycles. The most important tidal components have a periodicity close to semidiurnal or diurnal.

Global manifestation of the tides

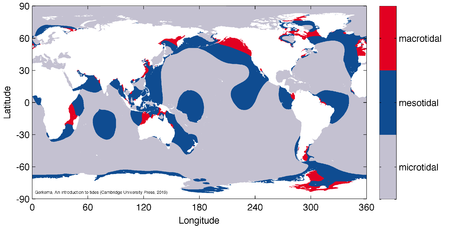

Fig. 1 maps the distribution of the principal periodicities worldwide. The tides are predominantly semidiurnal; diurnal tides occur in isolated patches, such as the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, the Indonesian archipelago, the North Pacific and around the Pacific Antarctic embayment. In Fig. 1, the mixed tides are subdivided depending on which of the two - diurnal or semidiurnal - is dominant.

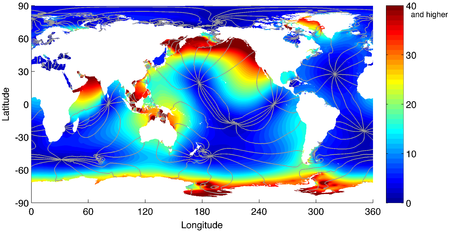

The amplitude of the oscillation of ocean waters can be expressed as the tidal range: the vertical interval between high and low water levels. The tidal range is commonly classified in three categories: macrotides (ranges exceeding 4 m), mesotides (between 2 and 4 m) and microtides (lower than 2 m). As shown in Fig. 2, macrotides occur only in patches that are attached to the continents -- an indication that the configuration of the continents acts as one of the organizing principles behind the global pattern of tides.

Fig. 1. Global distribution of semidiurnal, diurnal and mixed tides. This classification is based on the so-called form factor. Figure generated using Aviso+ products. Color version of a figure from Gerkema (2019)[1]. |

Fig. 2. Global distribution of the tidal range. Figure generated using Aviso+ products. Color version of a figure from Gerkema (2019)[1]. |

Tide generation

Moon and sun

The regular (twice-)daily up- and downward motion of the water surface along the coastline is the most visible expression of the tides. In ancient Greece it was recognized that tides are in some way related to sun and moon, but this relationship could not be explained [2]. The explanation of tidal motion as resulting from gravitational forces was given by Newton; the key to the tide-generating force lies in the spatial variation of lunar and solar gravity across the earth. The vertical component of the tide-generating force is dwarfed by terrestrial gravity, but its horizontal component, the tractive force, is what actually generates the tides. The tide-generating force of the moon is about twice as large as that of the sun.

Response

The connection between the tide-generating force and the response of the oceans and seas to this force is complex, as the response takes the form of tidal waves. At any location, the tidal signal is a blend of tidal waves generated across the basin and beyond. In the 19th century, the idea was put forward that the main region of origin of tides would be the belt of water around Antarctica, which is uninterrupted by the continents; from here the tidal waves would spread into the oceans. However, this idea was later disproved [3]. It was only in the era of satellite altimetry and global numerical modelling that the actual areas could be identified where the tide-generating force injects energy in the oceans. For the semidiurnal tide, the main areas of input are the South Atlantic Ocean and the western part of the Indian Ocean [4].

Tidal wave and ocean basin resonance

Ocean tides owe their strength for a large part to resonance; tidal motion is amplified for tidal components with a frequency close to the frequency of free oscillations in the ocean basins. This is the case in particular for the semi-diurnal tide in the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans [5], and also for the diurnal tide in the Pacific Ocean [6]. Tidal waves in wide ocean basins (width typically larger than a few thousand km) propagate around points of zero amplitude, the amphidromic points. This is due to earth's rotation, which induces Coriolis acceleration of tidal currents. Fig. 3 shows the semi-diurnal tidal wave in the world's oceans (i.e., the principal lunar semidiurnal component); it forms a pattern of amphidromic systems. This ocean tidal wave pattern can be described to a first approximation by a combination of Kelvin and Sverdrup waves (also called Poincaré waves, see Tidal motion in shelf seas).

It is to be noticed that the amphidromic patterns are different for different components (compare Figs. 3 and 4). In particular, the amphidromic points are located differently: where one component vanishes, the others can still be there.

Fig. 3. Global map of the principal lunar semidiurnal component ([math]M_2[/math]), with amplitude in centimeters, indicated in color. Co-phase lines (i.e., lines connecting points of equal phase) are shown in grey. Lags between neighboring lines represent a phase difference of 1/12 of the [math]M_2[/math] period (i.e., slightly more than one solar hour). Figure generated using Aviso+ products. Color version of a figure from Gerkema (2019)[1]. |

Fig. 4. Global map of the luni-solar declinational diurnal component ([math]K_1[/math]), with amplitude in centimeters, indicated in color. Co-phase lines (i.e., lines connecting points of equal phase) are shown in grey. Lags between neighboring lines represent a phase difference of 1/12 of the [math]K_1[/math] period (i.e., slightly less than two solar hour). Figure generated using Aviso+ products. Color version of a figure from Gerkema (2019)[1]. |

Tidal energy dissipation

The total power available from moon and sun on the global ocean is estimated at 3.7 TW ([math]10^{12}[/math] Watts); after allowing for a comparatively small dissipation in the atmosphere and the solid Earth, 3.5 TW remain to be dissipated in the ocean (Munk and Wunsch, 1998)[7]. For comparison, the geothermal heat loss is 30 TW, and the equator-to-pole ocean heat-flow is 2,000 TW. Solar radiation input (175,000 TW) is five orders of magnitude greater than the tidal power.

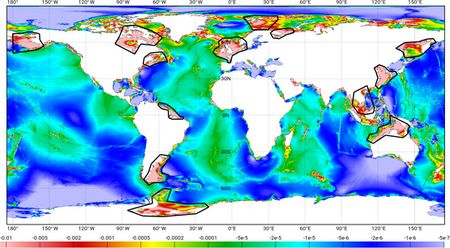

Most energy is dissipated in the turbulent bottom boundary layers of marginal seas due to the work against bottom friction which opposes tidal currents. This kind of energy dissipation is concentrated in a few shelf areas of strong tidal current (indicated by polygons in Fig. 5), such as the north-west European Shelf, the Patagonian Shelf, the Yellow Sea, the Timor and Arafura Seas, and the Amazon Shelf. Tidal energy is also dissipated in the open ocean through the conversion of surface tides into internal tides by ocean-bottom topography. This energy dissipation is related to breaking of internal tidal waves, which occurs near rugged bottom topography, for example seamounts and mid-ocean ridges (Fig. 6). Egbert and Ray (2000)[9] estimated that tidal energy dissipation takes place for about ¾ in the shallow shelf areas and for about ¼ by internal tidal wave breaking. Breaking internal tidal waves are a principal contributor to internal mixing of the interior ocean (Munk and Wunsch, 1998[7], Niwa and Hibiya, 2001[10]).

Global tidal models cannot resolve the relatively small-scale conversion to internal tides; this process therefore has to be parameterized [11]. Other factors that need to be taken into account in global tidal modelling are:

- Tide-induced seafloor deformation under the weight of the water column (loading tide);

- Tide-induced seafloor deformation related to the solid earth tide;

- Gravitational attraction induced by the mass of the ocean on the ocean itself (self-attraction).

See Hendershott (1981) [12] for a discussion of these different factors.

The FES2014 two-dimensional global tidal model (Lyard et al., 2021[8]) uses an internal tide wave drag parameterization for representing the energy transfer from the barotropic tides to the internal baroclinic tides; available explicit atlases are used to represent geometrical loading and gravitational self-attraction in the simulations.

Main tidal periods

The dominant tidal component is generally the principal lunar semidiurnal tide (Fig. 3). The semidiurnal period is due to the fact that the tangential component of the tide-generating force (the tractive force) is symmetric on the side facing the moon and the opposite side; hence during a daily rotation one passes the same forcing twice.

However, the lunar orbital plane has an angle with the equatorial plane. This creates an asymmetry, which causes an alternation of higher and lower high tides, the diurnal inequality. This alternation has a periodicity of twice a month as the moon crosses the equatorial plane bi-monthly.

The sun, earth and moon regain their relative positions once every 29.53 days, the synodic month. They are in line twice during this period (full moon or new moon), which causes spring tides to happen once every 14.8 days; the tide-generating forces of moon and sun then act in the same direction. They work against each other during first and third quarters, causing neap tides. Alternatively, the spring-neap cycle can be regarded as a beat in the superposition of the principal lunar and solar semidiurnal oscillations, due to their small difference in periods (one being 12.42 hours, the other 12 hours).

The various cycles in the relative motions of moon, sun and earth surface generate tidal oscillations at specific compound frequencies of these cycles. The lunar semidiurnal tidal component [math]M_2[/math] (period [math]\approx[/math] 12 h 25 min) is generally the largest tidal component, followed by the luni-solar diurnal constituent [math]K_1[/math] of 23 h 56 min (the sidereal day). Other important tidal constituents are:

- the principal solar semidiurnal component [math]S_2[/math], which has a period of 12 h,

- the diurnal lunar component [math]O_1[/math] (period [math]\approx[/math] 25 h 49 min).

There are also other tidal components of smaller magnitude and of (bi-)monthly or (bi-)yearly periods related to periodicity in the lunar and terrestrial orbits. They are called long-period tides. A modulation of the mean tidal amplitude of the order of 5% is related to the 18.6 year oscillation in the inclination of the lunar orbital plane, see Long-period lunar tides.

The tidal energy dissipation due to bottom friction in shelf seas is enhanced when tidal currents are superimposed on wind-driven water motions (surges, waves)[13]. This explains a small modulation of the semidiurnal tidal range observed at some tide gauge stations in the North Sea, where the mean [math]M_2[/math] amplitude in summer is a few percent larger than in winter[14].

Prediction of tides

Because the astronomical tide responds to a cyclic forcing by the gravitational motions of earth, moon and sun (including earth's rotation), tides are a cyclic phenomenon at any place on earth and can be predicted by analysing observations from the past. Therefore the amplitude and phase of all relevant tidal components need to be determined. The most usual method today is based on the least-squares technique [15]. The tidal elevation is represented by a sum of the (sinusoidal) tidal components that are expected to yield a significant contribution. The amplitudes and phases of the tidal components are free parameters which are determined by a least-square fit of the representation to the observed tidal elevation record. The tidal record should be sufficiently long to eliminate meteorological influences. The observation record should also be longer (at least a few times) than the largest period appearing in the representation. For resolving two components with close periods [math]T[/math] and [math]T+\Delta T[/math] the length of the observation record should exceed a few times [math]\; T^2 / \Delta T [/math]. For many stations around the world tidal predictions are available (see for example https://maree.shom.fr/) .

Asymmetric ocean tides

Because of the minor role of friction in the propagation of ocean tides, individual astronomic tidal components are well described by sinusoidal functions. This implies that for each component the rising and falling branches are symmetric. This also holds on average for a superposition of tidal components, if the frequencies [math]\omega_i[/math] of the major tidal components are not linearly related with integer coefficients ([math]\omega_i[/math] is different from any combination of sums and differences of [math]\omega_j, \; j \neq i[/math]). Taken over a sufficiently long time the average period of rising tide then equals the average period of falling tide. Hence, at the continental shelf boundary there is symmetry between the astronomical forcing of flood currents and ebb currents. Moreover, the long-term mean tidal period equals that of the largest component [16]

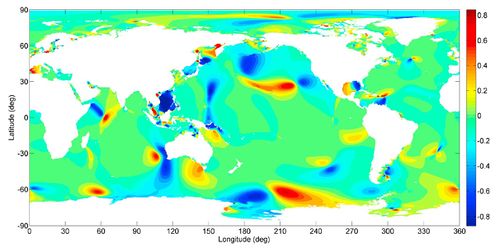

However, certain combinations of astronomic components yield asymmetric tides, irrespective of the averaging period. The reason is that most tidal constituents result from a superposition of a limited number of basic cycles in the relative motions of earth, moon and sun. The frequencies of these tidal constituents correspond to sums and differences of the basic frequencies [18]. This implies that different tidal constituents may interfere in such a way that flood and ebb are modulated in a systematic, asymmetric way. Such asymmetries may become significant in the case of strong diurnal tides [19]; for dominant semidiurnal tides this effect is small. Fig. 7 shows a world map of tidal asymmetry computed according to the tidal constants derived from TPXO7-ATLAS by Song et al. (2011)[17].

A particular example is the combination of the [math]M_2, K_1[/math] and [math]O_1[/math] tides. The sum of the frequencies of the [math]K_1[/math] and [math]O_1[/math] tidal constituents equals the frequency of the [math]M_2[/math] tidal constituent. In regions where the amplitudes of the [math]K_1[/math] and [math]O_1[/math] tides are not small compared to the amplitude of the [math]M_2[/math] tide, the sum of these three tidal constituents yields an asymmetric tide, with an asymmetry depending on the relative phase of these tidal constituents. Along the Californian coast, for example, the combination of [math]M_2, K_1[/math] and [math]O_1[/math] yields a tidal asymmetry with longer duration of rising tide compared to falling tide [20]. Duration asymmetry of tidal rise and tidal fall induces an asymmetry in the strength of flood and ebb currents in tidal inlets. This has consequences for residual sediment transport and for the morphology of the inward tidal basins (see Tidal asymmetry and tidal basin morphodynamics and Morphology of estuaries for more details).

Tides on the continental shelf and in coastal basins

Tidal amplification

The tides generated in the ocean propagate onto the continental shelf, where the tidal range may increase further. Different phenomena contribute to this amplification: resonant dimensions of the shelf sea, slowing down of wave-energy propagation ('shoaling') or concentration of the tidal energy flux in areas of reduced width ('funneling'). The maximum spring tidal range can exceed 14 m in some funnel-shaped bays, such as the Bay of Fundy (Canada), Bristol Channel (UK) and Baie du Mont Saint Michel (France).

Tidal amplification in shelf seas is counteracted by frictional momentum dissipation. The strong tidal motion occurring in many shelf seas is thus not locally produced by tide generating forces, but results from co-oscillation with ocean tides and from local topographic amplification. Numerical tidal studies for the northwest European shelf [21] and for the East China shelf [22] show that the local tide-generating force influences the co-oscillating semidiurnal tide in these shelf seas by no more than about 1%. Tidal resonance in shelf seas generally has a damping effect on ocean tides [23].

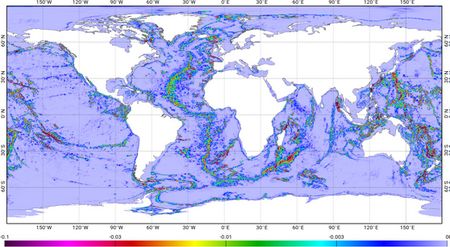

Higher harmonic components

Tides on the continental shelf are due to co-oscillation with the ocean tides at the continental shelf boundaries, as noted earlier. However, the non-linearity of tidal propagation in shallow environments (water depth not much greater than ten times the tidal amplitude, or less) alters the sinusoidal character of the ocean tide at the shelf boundary. The distortion of the tidal wave can be represented by additional tidal components corresponding to multiples (overtides) or superposition (compound tides) of the dominant ocean tidal frequencies [24][25][26]. An important consequence of tidal wave distortion is the asymmetric character of tidal motion in shallow water: the periods of tidal rise and tidal fall are not equal. This asymmetry is represented in particular by a quarter-diurnal tidal component (indicated by [math]M_4[/math]), which induces different strengths of flood currents and ebb currents. In Fig. 8, coastal regions are indicated with an important [math]M_4[/math] tidal component; they coincide largely with coastal zones where the semidiurnal tide is strong (Fig. 3). Fig. 8 also shows that the [math]M_4[/math] component radiates from the shelf into the ocean. Even though the primary pathway of tidal propagation is from ocean into shelf seas, it is actually a two-way traffic.

A study of tide asymmetry by Nunez et al. (2020[27]), applying methods similar to the study of Song et al. (2011[17]) to the more recent TPXO9 atlas and the GESLA-2 tide gauge dataset, confirmed that substantial tidal asymmetry in the open ocean is the exception rather than the rule. This even holds for shelf seas, where tidal asymmetry can be either positive or negative. In general, the astronomical triplet O1/K1/M2 determines the tidal asymmetry in the diurnal, mixed diurnal and mixed semi-diurnal regimes, while the M2/M4 component pair contributes most to the tidal asymmetry in areas where the semidiurnal tide dominates.

Tides in estuaries and tidal lagoons

The tidal wave is further distorted when entering coastal inlets and estuaries. This is due the shallowness of these systems (the water depth is in many cases no greater than a few times the tidal amplitude or even less) and due to interaction with the basin topography (for example, expansion of the tidal flood wave over intertidal flats). As a consequence of tidal asymmetry, substantial differences can arise between the strength of flood and ebb currents. This results in a net import or export of sediment and corresponding sedimentation or erosion, which affects the basin morphology. However, change of basin morphology will in turn cause change of tidal asymmetry. This morphodynamic feedback process and its consequences are described in more detail in the article Tidal asymmetry and tidal basin morphodynamics. Tidal distortion in some estuaries and shallow tidal lagoons may become so strong that the tidal flood wave evolves into a tidal bore. This process is described in more detail in the article Tidal bore dynamics.

Related articles

- Tidal motion in shelf seas

- Coriolis acceleration

- Long-period lunar tides

- Tidal asymmetry and tidal basin morphodynamics

- Morphology of estuaries

- Tidal bore dynamics

Further reading

Cartwright, D.E. 1999. Tides, a scientific history. Cambridge Univ. Press, UK, 292 pp.

A general introduction to sea-level variations, with several chapters on tides: Pugh, D., and Woodworth, P. 2014. Sea-Level Science: Understanding Tides, Surges, Tsunamis and Mean Sea-Level Changes. Cambridge University Press, 395 pp.

A non-mathematical descriptive introduction suited to laypersons: Bowers, D.G. and Roberts, E.M. 2019. Tides - a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 168 pp.

A physical and mathematical introduction useful for courses on tides and suited to researchers and engineers: Gerkema, T. 2019. An introduction to tides. Cambridge University Press, 222 pp.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Gerkema, T. (2019), An introduction to tides. Cambridge Univ. Press Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "TG" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Ekman, M. 1993. A concise history of the theories of tides, precession-nutation and polar motion. Surveys in Geophysics 14: 585-617

- ↑ Doodson, A.T. 1958. Oceanic tides. Adv. Geophys. 5: 117-152

- ↑ Lyard F.H. and Le Provost, C. 1997. Energy budget of the tidal hydrodynamical model FES94.1. Geophys. Res. Lett. 24(6): 687-690

- ↑ Heath, R.A. 1981. Estimates of the resonant period and Q in the semi-diurnal tidal band in the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Deep-Sea Research. Vol. 28A: 481 – 493

- ↑ Müller, M. 2007. The free oscillations of the world ocean in the period range 8 to 165 hours including the full loading effect. Geophys. Res. Letters 34, L05606, doi:10.1029/2006GL028870, 2007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Munk, W. H. and Wunsch C. 1998. Abyssal recipes II: Energetics of tidal and wind mixing, Deep-Sea Research 45: 1977-2010

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Lyard, F.H., Allain, D.J., Cancet, M., Carrere, L. and Picot, N. 2021. FES2014 global ocean tide atlas: design and performance Ocean Sci., 17, 615–649, 2021

- ↑ Egbert, G. D., and R. D. Ray (2000), Significant dissipation of tidal energy in the deep ocean inferred from satellite altimeter data, Nature, 405, 775-778

- ↑ Niwa, Y. and Hibiya, T. 2001. Numerical study of the spatial distribution of the M2 internal tide in the Pacific Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research Oceans 106: 22441–22449

- ↑ Green, J.A.M and Nycander J. 2013. A comparison of tidal conversion parameterizations for tidal models. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43: 104-119

- ↑ Hendershott, M.C. 1981. Long Waves and Ocean Tides. In: Evolution of Physical Oceanography (Eds. B. Warren, and C. Wunsch) MIT OpenCourseWare, https://ocw.mit.edu

- ↑ Hashemi, M.R., Neill, S.P., Robins, P.E., Davies, A.G. and Lewis, M.J. 2015. Effect of waves on the tidal energy resource at a planned tidal stream array. Renewable Energy 75: 626-639

- ↑ Huess, V. and Andersen, O.B. 2001. Seasonal variation in the main tidal constituent from altimetry. Geophysical Research Letters 28: 567–570

- ↑ Parker, B.B. 2007. Tidal Analysis and Prediction. NOAA Special Publication NOS CO-OPS 3

- ↑ Gerkema, T. 2019. An introduction to tides. Cambridge Univ. Press

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Song, D., X. H. Wang, A. E. Kiss, and Bao, X. 2011. The contribution to tidal asymmetry by different combinations of tidal constituents. J. Geophys. Res., 116, C12007

- ↑ Doodson, A.T. 1921. The harmonic development of the tide-generating potential. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser.A 100: 305-329

- ↑ Hoitink, A.F.J., Hoekstra, P. and van Mare, D.S. 2003. Flow asymmetry associated with astronomical tides: Implications for residual transport of sediment. J.Geophys.Res. 108: 13-1 - 13-8

- ↑ Nidzieko, J. 2010. Tidal asymmetry in estuaries with mixed semidiurnal/diurnal tides. J. Geophysical Research 115, C08006, doi:10.1029/2009JC005864

- ↑ Pingree, R.D. and Griffiths, D.K. 1987. Tidal friction for semidiurnal tides. Cont.Shelf Res. 7: 1181-1209

- ↑ Kang, S.K., Lee, S.R. and Lie, H.J. 1998. Fine-grid tidal modelling of the Yellow and East China seas. Cont.Shelf Res. 18: 739-772

- ↑ Arbic, B.K., Karsten, R.H. and Garrett, C. 2009. On tidal resonance in the global ocean and the back‐effect of coastal tides upon open‐ocean tides. Atmosphere-Ocean, 47: 239-266

- ↑ Aubrey, D.G. and Speer, P.E. 1985. A study of non-linear tidal propagation in shallow inlet/estuarine systems. Part I: Observations. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 21: 185-205

- ↑ Friedrichs, C. T., and Aubrey, D. G. 1988. Non-linear tidal distortion in shallow well-mixed estuaries: a synthesis. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 27: 521-545

- ↑ Boy, J.-P., Llubes, M., Ray, R., Hinderer, J., Florsch, N., Rosat, S., Lyard, F. and Letellier, T. 2004. Non-linear oceanic tides observed by superconducting gravimeters in Europe. J. Geodynamics 38: 391–405

- ↑ Nunez, P., Castanedo, S. and Medina, R. 2020. A global classification of astronomical tide asymmetry and periodicity using statistical and cluster analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 125, e2020JC016143

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|