Coastal meteorology

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Boundary Layer Processes, Air-Sea Interaction aspects

- 3 Thermally driven effects, the land-sea breeze

- 4 Coastally-trapped disturbances

- 5 Orographic Influences

- 6 Interactions with large scale meteorological systems

- 7 Meteorological measurements in the coastal environment

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 Further reading

Introduction

The coastal zone often experiences a unique weather which results into a very special climate. Coastal meteorology is the study of meteorological phenomena within about 100 km inland or offshore of a coastline. Improved understanding of the processes in the meteorology of the coastal zone is based on detailed knowledge of marine and terrestrial boundary layers and air-sea-interaction but has also to consider large-scale atmospheric dynamics and circulation of the coastal ocean. In addition to the importance of coastal meteorology to coastal weather forecast the subject helps in understanding the physical, chemical and biological aspects of the coastal ocean. Furthermore, the application of the knowledge is vital for the prediction of sea state and pollutant dispersal, and it is also important for public safety, ship routing and naval operations. The phenomena in coastal meteorology are caused, or significantly affected, by sharp changes in heat, moisture, and momentum transfer and changes in elevation, often a complex orography (topographic relief), that occur between land and water. Thermally driven effects like the land-sea breeze and orographically induced flows are the most prominent features in coastal meteorology, but also coastal cloud systems and fog, low level jets, coastal fronts and land-falling hurricanes, whose low-level flows are often modified as to favour the formation of tornadoes, are aspects of coastal weather phenomena. Complex terrain or coastlines and marine boundary layer stratus (cloud base) complicate the subject of coastal meteorology.

Boundary Layer Processes, Air-Sea Interaction aspects

The atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) is the lowest layer of the atmosphere which most directly is influenced (on time scales of an hour or less) by the presence (roughness) of the earth / ocean surface. Turbulent motions dominate the flow in this region. Strong momentum, heat, water vapour, trace gas and particle transfer occurs at the air-land and air-sea interface which is mainly driven by turbulent motions (Garratt, 1995 [1]). The ABL is the region where life and human activities predominantly take place (Arya, 2001)[2]

Thermally driven effects, the land-sea breeze

There is generally a large thermal contrast between the ocean and the land that drives the well-known sea-breeze circulation, which results in the confluence of air originating over the ocean with air originating over the land. The sea-breeze is associated with many processes that contribute to the recirculation and trapping of pollution, the evolution of precipitating convective storms, the creation of strong nearshore thermal, moisture and aerosol gradients, and the formation and transport of fog and low cloud in the coastal zone.

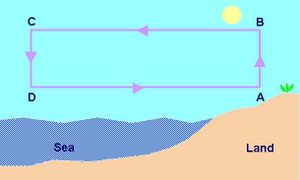

Qualitative description of a sea breeze mechanism in a calm atmosphere during a clear day (Fig. 1):

- air over land heats up and expands more rapidly than that over water

- hydrostatic vertical pressure gradient larger in cooler air over water

- there is a level where pressure is higher over land than over water

- pressure gradient produces slight flow from B to C

- convergence near C leads higher pressure and subsidence from C to D

- departure from hydrostatic equilibrium around D and flow from D to A (sea breeze)

- divergence near B leads to decrease in pressure and flow from A to B

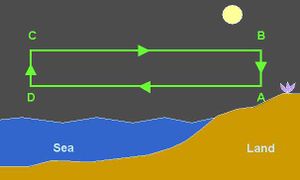

Qualtitative description of a sea breeze mechanism in a calm atmosphere during a clear night (Fig. 2):

- at night the land cools more rapidly than the sea

- at upper levels pressure relatively high over sea and low over land

- there is a level where pressure is higher over water than over land

- pressure gradient produces slight flow from C to B

- convergence near B leads to higher pressure and subsidence from B to A

- departure from hydrostatic equilibrium around A and flow from A to D (land breeze)

- divergence near D leads to decrease in pressure and flow from D to C

Coastally-trapped disturbances

Coastally-trapped disturbances that exist for between two and six days, can have length scales of 1000 km in the alongshore direction and 100-300 km across-shore. These features generally cause significant changes in the local weather in the coastal zone, for example, replacing clear skies with clouds and fog (Fig. 3), and causing intensification and reversals of the wind field as the system moves along the coast.

Coastal marine fog (or sea fog, see Fig. 3) usually occurs when relatively warm, moist air passes over a cooler sea surface. The cold air just above the sea's surface cools the warm air above it until it can no longer hold its moisture. Tiny fog particles are formed when the moist air condenses on aerosol particles (salt spray, dust or micro-organisms) that are omnipresent in the air above the sea.

Orographic Influences

Coastal mountains (Fig. 4) form a barrier to the wind field that may affect both the downstream and upstream evolution of the flow. The phenomenon is characterized by two free parameters:

- the Rossby number [math]R_o[/math], defined by [math]R_o=U/(fl_m)[/math], where [math]U[/math] is the speed of the air stream, [math]f[/math] is the Coriolis parameter and [math]l_m[/math] is the half-width of the barrier.

- the Froude number [math]F_r[/math], defined by [math]F_r=U/(Nh_m) [/math], where [math]h_m[/math] is the height of the barrier and [math]N[/math] is the Brunt-Vaisala frequency, which is given by [math]N= \sqrt{(g/\theta) (d\theta/dz)}[/math], where [math]g[/math] is gravity acceleration, and [math]\theta[/math] is the potential temperature (the temperature that an air parcel at height [math]z[/math] would attain if it was moved dry adiabatically to a standard pressure [math]p_0=[/math]1000 mb; in formula: [math]\theta=T \, (p/p_0)^{0.286} \,[/math], where [math]p[/math] and [math]T[/math] are the pressure and absolute temperature at height [math]z[/math]).

The influence of earth's rotation on the deceleration of the upstream flow depends mainly on [math]R_o[/math]. Deceleration is insignificant in the case of a broad coastal maintain range (large [math]l_m[/math]) such that [math]R_o \lt 1[/math]. In this case the flow will remain approximately geostrophic (i.e. perpendicular to the pressure gradient).

It can been shown that for steep topography, the deceleration zone will grow upstream to a width given by the Rossby radius of deformation [math]l_r = Nh_m/f[/math]. Steep topography is defined by the non-dimensional slope [math] R_o/F_r \equiv l_r/l_m \equiv ( h_m/l_m)(N/f) \gt 1[/math]; the air flow in the coastal region often 'feels' the mountains as representing a wall. If [math]R_o \gt 1[/math] the flow is not expected to be geostrophic (i.e., the flow will not remain perpendicular to the pressure gradient). The offshore influence of mountain coasts is given by the Rossby radius of deformation, which typically varies from 10 to 100 km.

The air flow will be blocked if it encounters a coastal barrier with [math]F_r \lt 1[/math], which can occur with elevations as low as [math]h_m=[/math]100 m for a typical value of [math]N \sim 10^{-1} s^{-1}[/math]. The steady-state response is a pressure ridge, a phenomenon referred to as damming. The topographically induced pressure fields produce along-ridge pressure gradients that can result in alongshore barrier jets. The best examples of the phenomenon are found associated with cold air damming between a coastal front and mountain ridges. A similar structure can occur when the incident flow is not uniform, such as in the vicinity of a storm.

Interactions with large scale meteorological systems

Many of the meteorological phenomena that are associated with the coast are a consequence of synoptic-scale forcing. Traveling disturbances as they pass over the coastline can be strongly modified and lead to new phenomena that are peculiar to the coastal region. Land-falling storms are directly modified in the coastal region where changes in the bottom boundary conditions are dramatic. Severe storms affect many coastal regions during the winter and, to a lesser extent, in summer. Regional differences exist, with oceanic extratropical cyclones affecting the coast and continental extratropical cyclones moving from the interior of the continents to the coast. Tropical cyclones, including hurricanes, may affect almost any part of the coasts in the tropics during summer and fall. Particularly important effects are caused e.g. by cold air outbreaks along the east coast of the United States and by rapidly intensifying storms over the Gulf Stream. Hurricanes/typhoons weaken over land because of the absence of latent heating at the surface. Orographic barriers can affect the dynamics of the storm through blocking and actually enhance precipitation and winds in coastal areas. Increased friction over the land decreases the surface winds, which cause an expansion of the radius of the eye wall (the location within a hurricane where the most damaging winds and intense rainfall is found). This can cause an increase in the vertical wind shear, which may explain the occurrence of tornadoes in these storms. Many of the meteorological phenomena that are associated with the coast are a consequence of synoptic-scale forcing; for example, the formation of coastally-trapped Kelvin waves and low level frontogenesis caused by large gradients in surface temperature. The response time of the coastal currents are sufficiently short that changes in the shelf circulation can be driven by rapidly moving atmospheric events. Intense storms along coastlines or ice edges at high latitudes appear to form over water just beyond the ice edge, where the large vertical temperature gradient between the water and the air leads to strong low level baroclinicity. It has been shown that some polar lows can attain the intensity and structure commonly associated with hurricanes.

Meteorological measurements in the coastal environment

Understanding the coastal atmosphere requires a multidisciplinary approach to combine research on air motions, cloud physics, aerosol dynamics, convection, air-sea gas exchange, surface waves and fluxes, boundary layer dynamics, and large scale storm systems to investigate interactions and feedbacks between these processes. Therefore the suite of meteorological instruments and well organized measurement strategies are needed to capture the relevant parameters of the coastal atmosphere and air-water interface (Fig. 5).

The small space and time scales associated with the coastal zone place severe demands on measurement systems. Space-borne remote sensing systems have the potential to measure phenomena both over the coastal ocean and over the land. The required spatial resolution is also provided by satellite data from recently launched systems, in addition to routine photogrammetry of clouds and infrared imagery.

See also

Related articles

Articles about coastal wind field observation:

- WiSAR - Wind retrieval from synthetic aperture radar

- WiRAR - A marine radar wind sensor

- Use of X-band and HF radar in marine hydrography

- Proudman resonance and meteo tsunamis

External link

References

Further reading

Geernaert, G.L. (ed.), 1999: Air-Sea Exchange: Physics, Chemistry and Dynamics. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 578pp.

Hsu, S.A., 1988: Coastal meteorology. Academic Press Inc., San Diego, 260pp. Kraus, E.B. and J. A. Businger, 1994: Atmosphere-Ocean Interaction. Oxford University Press, 362 pp.

Nuss, W.A., J.M. Bane, W.T. Thompson, T. Holt, C.E. Dorman, F.M. Ralph, R. Rotunno, J.B. Klemp, W.C. Skamarock, R.M. Samelson, A.M. Rodgerson, C. Reason, and P. Jackson, 2000: Coastally trapped wind reversals: Progress toward understanding. Bull. Amer. Meteoro. Soc., 81, 719-743.

Nuss, W., 2002: Coastal Meteorology. In M. Shankar (ed.) Enzyclopedia of Atmospheric Science, Elsevier, in Press.

Rogers, D.P., 1995: Coastal meteorology. U.S. National Report to IUGG 1991-1994, American Geophysical Union Rev. Geophys. Vol. 33 Suppl.

Rogers, D., C. Dorman, K. Edwards, I. Brooks, S. Burk, W. Thompson, T. Holt, L. Strom, M. Tjernström, B. Grisogono, J. Bane, W. Nuss, B. Morely and A. Schanot, 1998.: Highlights of Coastal Waves 1996. Bull. Amer. Meteoro. Soc., 79, 1307-1326.

National Research Council 1992. Coastal Meteorology: A Review of the State of the Science. The National Academies Press, Washington, D. C., 99 pp.

Simpson, J.E., 1994: Sea Breeze and Local Winds. Cambridge University Press.

Rohli, R.V. and Li, C. 2021. Meteorology for Coastal Scientists. Springer International Publishing, pp. 525. ISBN 978-3-030-73092-5

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|