Difference between revisions of "Salt marshes"

(→Case-study: Land van Saeftinghe) |

Dronkers J (talk | contribs) |

||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This article describes the habitat of | + | |

| + | This article describes the habitat of salt marshes or saltmarshes (the notation used in this article). It gives an introduction to the characteristics, distribution, evolution, adaptations, [[zonation]], succession, biota, functions and threats of the organisms that live in saltmarshes. | ||

| + | |||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | + | Saltmarshes are defined as natural or semi-natural terrestrial halophytic ecosystems that occur in the [[intertidal]] zone between the land and the sea and that are covered by salty or brackish water for part of the time. They can be considered, in some way, as the analogue of [[mangrove]]s in temperate and arctic regions. The dominant flora is composed of [[Halophytic plants|halophytic plant]]s such as grasses, shrubs and herbs. The flora is locally rather species poor, but the global species diversity is high, with over 500 saltmarsh plant species known<ref name=S14>Silliman, B.R. 2014. Saltmarshes. Current Biology 24(9) R348</ref>. Saltmarshes are normally associated with [[mud]] flats but also occur on sand flats. These [[Tidal flats from space|mud flats]] are sometimes dominated by [[algae]] and covered with algal mats. They are periodically flooded by the tide, the height of which can vary from several centimetres in enclosed seas (such as the Baltic Sea) to several metres in open bays, estuaries and tidal lagoons. A network of meandering tidal creeks ensures the drainage of seawater. Through these channels, sediments, [[detritus]], dissolved [[nutrient]]s, [[plankton]] and small fishes are flushed in and out the saltmarshes. | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

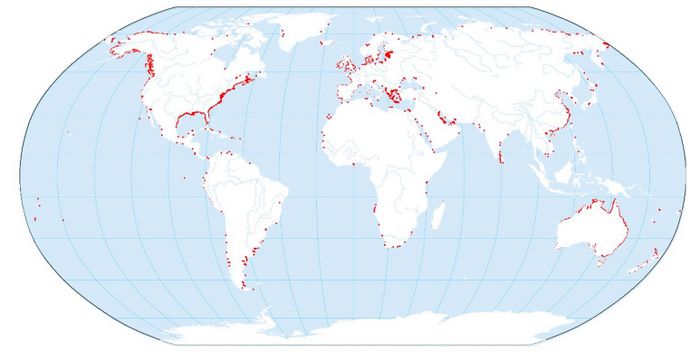

| + | ==Distribution== | ||

| + | Saltmarshes are ubiquitous in estuarine systems in temperate zones all over the world. They seldom occur on open coasts, because the development is inhibited by strong wave action. Although sediment is a prerequisite for their growth in height and width, saltmarsh communities can develop in areas with limited or no sediment supply. Examples include seawater-drenched cliffs and slopes on exposed coasts, at the head of sea lochs and rocky beaches (Doody 2008<ref>Doody, J.P. 2008. Saltmarsh Conservation, Management and Restoration''. Coastal Systems and Continental Margins, Volume 12, Springer, 217 pp. </ref>). The most extensive development of saltmarshes occurs in estuaries with a moderate climate, large tidal range, abundant fine-grained sediments and sheltered locations where particles can settle out of the water column. Globally, saltmarshes are most extensive along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America (~40% of the shoreline), the European Atlantic coasts (~25%), the Mediterranean Sea (~9%), and Australia (~25%), with Eastern Asia (especially Russia, China, Korea, and Japan) also hosting marsh coverage comparable to that of Australia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:GlobalDistributionSaltMarshes.jpg|center|thumb|700px|caption|Global distribution of saltmarshes. From Mcowen at al. 2017 <ref>Mcowen, C., Weatherdon, L.V., Bochove, J., Sullivan, E., Blyth, S., Zockler, C., Stanwell-Smith, D., Kingston, N., Martin, C.S., Spalding, M. and Fletcher, S. 2017. A global map of saltmarshes (v6.1). Biodiversity Data Journal 5: e11764. Paper DOI: https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.5.e11764</ref>. Creative Commons Licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Saltmarsh evolution== | ||

| + | Saltmarshes evolve over time from young marshes to old marshes. At the time that the marsh surface builds up above the high water level, high marsh species invade, outcompete and replace the low marsh plants. The most stress-tolerant plant species occupy the lower reaches of the marshes while less specialized competitive species occupy the upper elevations that are less stressful<ref name=S14/>. Deposition of fine sand and mud raises the marsh to the highest tidal water levels. The marsh then becomes dry land almost disconnected from ocean influences<ref name=P98>Pinet P.R. 1998. Invitation to Oceanography. Jones and Barlett Publishers. p. 508</ref>. A cliff develops at the seaward edge of old marshes. Little water flows through the tidal channels of these high marshes. Lateral channel migration and wave attack at the base of marsh cliffs are the main mechanisms for erosion of mature saltmarshes and their subsequent rejuvenation cycle<ref>Levoy, F., Anthony, E.J., Dronkers, J., Monfort, O. and Montreuil, A-L. 2019. Short-term to Decadal-scale Sand Flat Morphodynamics and Sediment Balance of a Megatidal Bay: Insight from Multiple LiDAR Datasets. Journal of Coastal Research SI 88: 61–76</ref><ref>Mariotti, G. and Fagherazzi, S. 2013. Critical width of tidal flats triggers marsh collapse in the absence of sea-level rise, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110(14): 5353–5356</ref>, see [[Tidal channel meandering and marsh erosion]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Requirements for development== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The requirements for development of saltmarshes are: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * They need supply of fine-grained sediments. | ||

| + | * They must be sheltered from strong waves. | ||

| + | * They need salty (but not hypersaline) conditions to grow. They are halotolerant and have adaptations to these conditions. | ||

| + | * They need a temperate or cool temperature. Incidental freezing temperatures are not damaging the plants. | ||

| + | * They need a tidal range. This is important because it limits the [[erosion]], makes deposition of sediments possible and causes a well-marked [[zonation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

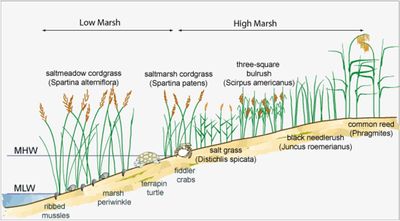

| + | ==Saltmarsh zonation== | ||

| + | [[image:ZonationSaltMarshes.jpg|left|thumb|400px|Zonation of saltmarshes. Image credit: USGS]] | ||

| − | + | Based on the topography and characteristic plant assemblages, saltmarshes are classified as low, medium and high marshes. This classification is related to the number of tidal submergences per year (Adam 1990<ref name=A90>Adam, P., 1990. ''Saltmarsh Ecology''. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge</ref>). The young, lower marsh is regularly inundated by salt water and vegetation is restricted to pioneer genera such as ''Salicorna'', ''Suaeda'', ''Aster'' and ''Spartina''. The middle marsh typically is typically situated in the zone between the mean and spring high tidal levels. The low and middle marshes are drained by tidal creeks that convey flood and ebb flow; ebb flow generally dominates because flood water also inundates the marsh directly from the main channels. When the rising tide exceeds the capacity of the creeks, the overspilling waters deposit the coarse fraction of the sediment load near the channel margins, leading to the development of creek levees<ref>Temmerman, S., Govers, G., Meire, P. and Wartel, S. 2004. Simulating the long-term development of levee-basin topography of tidal marshes. Geomorphology 63: 39-55</ref>. In warm climates and with inadequate drainage, evaporation can raise the salinity of the middle marsh<ref>Pennings, S.C. and Bertness, M.D. 1999. Using latitudinal variation to examine effects of climate on coastal saltmarsh pattern and process. Current Topics in Wetland Biogeochemistry 3: 100-111</ref>. Middle marshes with higher salinity are vegetated by more salt-tolerant flora. Salt accumulation can also lead to the development of bare areas known as salt pans. The high marsh extends from the mean spring high water level to the highest springtide level. Flooded only by the highest tides and during storms, the high marsh is more like a terrestrial than a true marine environment. In coastal areas with sufficient freshwater infiltration, rainfall, and high groundwater levels, the salinity decreases from the middle to the upper saltmarsh, where a range of floristically diverse wetland communities can develop<ref name=P19>Pratolongo, P., Leonardi, N., Kirby, J.R. and Plater, A. 2019. Temperate Coastal Wetlands: Morphology, Sediment Processes, and Plant Communities. Chapter 3 in Coastal Wetlands, An Integrated Ecosystem Approach (Second Edition), p. 105-152</ref>. Typical high marsh species are cordgrass ''Spartina patens'', spike grass ''Distichlis spicata'' and species such as saltwort ''Salsola'' and seablite ''Suaeda''. To successfully establish, annual species depend on yearly seed recruitment. Perennial species also benefit from establishment by seeds to colonize new areas. Conditions favorable for germination include a minimum bed level, where disturbance by wave and currents is low, and reduced soil salinity, for example through precipitation<ref>van Regteren, M., Amptmeijer, D., de Groot, A.V., Baptist, M.J. and Elschot, K. 2020. Where does the saltmarsh start? Field-based evidence for the lack of a transitional area between a gradually sloping intertidal flat and saltmarsh. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 243: 106909</ref>. | |

| − | == | + | {| border="0" align="center" |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SpartinaPatens.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Spartina patens'' Credit T. Forney www.pest.ceris.purdue.edu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SpartinaAlterniflora.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Spartina alterniflora'' Credit Janet Wright Creative Commons Licence]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SalsolaKaliES.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Salsola kali'' Credit Ed Stikvoort www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SuaedaMaritima.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Suaeda maritima'' Credit Ed Stikvoort www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Succession== | ||

| + | Succession is the successive development in time of different vegetation types at one place. It is a complex process; the factors determining zonation and succession in saltmarshes are discussed more in detail in Adam (1990<ref name=A90/>, pages 49-57), Gray (1992<ref>Gray, A.J. 1992. Saltmarsh plant ecology. In: ''Saltmarshes: morphodynamics, conservation and engineering significance'', J.R.L., Allen, & K., Pye, eds., 63-79. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.</ref>) and Packham & Willis (1997, pages 107-114 <ref>Packham, J.R. & Willis, A.J., 1997. ''Ecology of dunes, saltmarsh and shingle''. Chapman & Hall, London.</ref>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| border="0" align="left" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:Biofilm.jpg|thumb|left|175px|Biofilm of unicellular algae <ref name="multiple"> Credit Eric Coppejans - http://www.vliz.be/imis/imis.php?module=person&persid=134</ref>]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:Filamentous algae.JPG|thumb|left|175px|Fixation of the sediment by blue-green and green algae <ref name="multiple"/>]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mudflat colonization starts with unicellular algae such as diatoms sticking the sand together by production of mucus. This causes a brownish biofilm on the substrate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After this stage, filamentous [[algae]] contribute to the further fixation of sediments. These [[algae]] are mostly blue-green algae, Cyanophyta and Chlorophyta. Small gastropods can feed and develop in huge quantities on it. Locally, the filamentous alga ''Vaucheria'' can form banquettes or elevations. Brown algae can be associated with this stage. | ||

| + | <br clear=all> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A next stage is the germination of species such as the glasswort ''Salicornia''. The seeds germinate after partial desalination of the soil by rain. Sedimentation between and around the glassworts contributes to elevating and stabilizing the substrate. Other species such as ''Spartina maritima'' and ''Spartina anglica'' compete for the same place. ''S. maritima'' is an indigenous species of continental Europe and ''S. anglica'' is imported from the British Islands. The hybridisation and invasion of "Spartina" spp is a worldwide phenomenon<ref>Strong, D.R. and Ayres, D.R. 2013. Ecological and Evolutionary Misadventures of Spartina. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 44: 23.1–23.22</ref>. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {| border="0" align="center" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SalicornaEuropaea.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Salicorna europaea'' Credit Bart Vastenhouw, www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SpartinaMaritima.jpg|thumb|left|200px|''Spartina maritima'' Credit Ed Stikvoort www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:SpartinaAnglica.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Spartina anglica'' Credit Ed Stikvoort www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | |||

| + | Initial plant colonizers play an important role in the recovery of saltmarsh vegetation from disturbance events. They provide shading of the substrate of bare areas and reduce salt accumulation in the soils and thereby facilitate colonization by many other plant species<ref name=S14/>. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Saltmarsh vegetation== | |

| + | In Europe, typical vegetation pattern includes a pioneer zone with a sparse cover of ''Spartina anglica'' and ''Salicornia dolichostachya/fragilis''. Landward, ''Puccinellia maritima'' appears as small clones, and a middle marsh establishes with higher vegetation cover and diversity. ''Aster tripolium'', ''Cochlearia danica'', ''Salicornia ramosissima'', ''Suaeda maritima'', ''Halimione portulacoides'', ''Plantago maritima'', ''Limonium vulgare'', ''Bostrychia scorpiodes'' and ''Atriplex portulacoides'' may also appear in this zone, whereas ''Festuca rubra'', ''Juncus gerardii'' and ''Elymus athericus'' are common dominants in the upper marsh. ''Elymus'' invasions are facilitated by enrichment of water by nitrogenous compounds. | ||

| − | == | + | {| border="0" align="center" |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:PuccinelliaMaritima.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Puccinellia maritima'' Credit Peter Meininger www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:PlantagoMaritima.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Plantago maritima'' Credit Jeroen Willemsen www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:TriglochinMaritima.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Triglochin maritima'' Credit Hans Boll www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:AsterTripolium.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Aster tripolium'' Credit Jan van der Straaten www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | {| border="0" align="center" | |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:CochleariaDanica.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Cochlearia danica'' Credit Ed Stikvoort www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:LimoniumVulgare.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Limonium vulgare'' Credit Rutger Barendse www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:HalimionePortulacoides.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Halimione portulacoides'' Credit Jan van der Straaten www.freenatureimages.eu]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:BostrychiaScorpiodes.jpg|thumb|left|150px|''Bostrychia scorpiodes'' Credit Andre Rio. www.Marevita.org]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | In southern Europe, typical saltmarsh communities include species such as ''Sarcocornia fruticosa'' and ''Arthrocnemum macrostachyum'' on the low marsh, ''Limonium virgatum'', ''Limonium girardianum'', ''Frankenia pulverulenta'' and ''Artemisia galla'' on the middle marsh, and ''Juncus spp.'' and other low shrubby species on the high marsh<ref name=P19/>. | ||

| − | = | + | In eastern North America, dense tall stands of ''Spartina alterniflora'' grow in the lower intertidal zone, whereas in contrast, vegetation of European saltmarshes is typically confined to the upper intertidal zone. At higher elevations, marshes are dominated by ''Spartina patens''. Larger marshes in the Gulf of Maine are more likely to have waterlogged pans, comprising forbs such as ''Agalinis maritima'', ''Atriplex patula'', ''Glaux maritima'', ''Limonium nashii'', ''Plantago maritima'', ''Salicornia europaea'', ''Suaeda linearis'', and ''Triglochin maritima''. South of the Chesapeake Bay to northern Florida, ''Spartina alterniflora'' dominates extensive intertidal low marshes that cover most of the coastal marsh area. ''Spartina alterniflora'' marshes along the Coastal Plain have undergone extensive diebacks, characterized by the premature browning of this species. ''Spartina alterniflora'' has invaded many saltmarshes along the Pacific coast. of North America. ''Spartina foliosa'' is the only cordgrass species native to the Pacific coast of North America, from Humboldt Bay to Baja California<ref name=P19/>. |

| − | + | In China, the endemic ''Scirpus mariqueter'' marsh vegetation has been largely replaced by ''Spartina alterniflora'', that has also invaded originally bare mudflats and coastal wetlands with ''Phragmites australis'' and ''Suaeda salsa''<ref>Gao, S., Du, Y., Xie, W., Gao, W., Wang, D. and Wu, X. 2014. Environment-ecosystem dynamic processes of Spartina alterniflora salt-marshes along the eastern China coastlines. Science China Earth Sciences 57: 2567-2586</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| + | Monospecific stands of ''Spartina alterniflora'' also dominate the coastal wetlands from southern Brazil to the coastal plain southward from the Río de la Plata Estuary. At higher elevations within this humid region, the middle saltmarshes are dominated by mixed and monospecific stands of the southern cordgrass ''Spartina densiflora''<ref>Costa, C.S.B., Marangoni, J.C. and Azevedo, A.M.G. 2003. Plant zonation in irregularly flooded salt marshes: relative importance of stress tolerance and biological interactions. Journal of Ecology 91: 951-965</ref>. | ||

| − | |||

| + | ==Adaptations== | ||

| − | + | Plants and animals living in the low and middle saltmarsh must have adaptations to deal with the harsh physical stressors found in this intertidal habitat, including high salt concentrations, intense heat, and low oxygen in waterlogged soils. Some typical adaptations are discussed below. | |

| − | + | The saline environment causes waterstress. Plants have to take up water against the [[Osmosis|osmotic pressure]]. To overcome the negative osmotic pressure, they generate a negative hydrostatic pressure (by transpiration processes). They have thin, fleshy leaves and are sensitive to extra stress such as pollution. Anatomically, the plants are adapted through strong lignification, a well-developed epidermis and succulent leaves and stems. Evaporation can be limited by thin leaves with scale-like hairs. Physiologically, plants are adapted by accumulating salt in their tissues. In this way, normal [[osmosis]] is possible. Other plants have salt gland cells on the lower surface of the leaves and excrete the salt from its tissue. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:MarshPonds.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Mudflat and marsh of the Seine estuary. Photo credit: GIP Seine Aval. The marsh is covered with numerous ponds. Marsh pond formation is characteristic of waterlogged marshes with poor drainage, affecting soil biogeochemistry and implying toxicity to vegetation by high sulfide and ammonium concentrations. It is assumed that pond formation is related to root zone degradation that leads to erosion and collapse of otherwise cohesive marsh soils<ref>Himmelstein, J., Vinent, O.D., Temmerman, S. and Kirwan, M.L. 2021. Mechanisms of Pond Expansion in a Rapidly Submerging Marsh. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:704768</ref>.]] | |

| − | + | Saltmarsh plants have to deal with an anoxic environment. The tissue of the plants requires oxygen for [[respiration]]. Gas diffusion between sediment particles only occurs in soils that are not waterlogged. Even when the surface water is saturated with oxygen, its concentration in the soil is too low because of the slow oxygen diffusion. Many saltmarsh plants can temporarily cope with low soil oxygen levels by shunting oxygen down to their roots through straw-like vascular tissue called aerenchyma. Roots are superficial systems because of the anoxic sediments. They consist of perennial thick roots with a corky layer and without root hairs. To fix the substrate, short-lived, thin and highly branched roots are developed with numerous root hairs to absorb nutrients. | |

| − | + | Nitrogen limitation can also play a role in the development of saltmarsh vegetation, even though nitrogen levels can be very high. The reason is that concentrations of sulfide and sodium ions are often high too and interfere with nitrogen uptake by plants<ref name=S14/>. | |

| + | Saltmarsh plants do not tolerate permanent waterlogging. Such conditions exist in depressions of flat, poorly drained marsh areas, where marsh ponds form. These ponds are filled with stagnant anoxic water where collapse of peat soil is caused by microbial mineralization of organic matter<ref>Hutchings, A.M., Antler. G., Wilkening, J.V., Basu, A., Bradbury, H.J., Clegg, J.A., Gorka, M., Lin, C.Y., Mills, J.V., Pellerin, A., Redeker, K.R., Sun, X. and Turchyn, A.V. 2019. Creek Dynamics Determine Pond Subsurface Geochemical Heterogeneity in East Anglian (UK) Salt Marshes. Front. Earth Sci. 7: 41</ref>. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Functions== | ||

| + | Attenuating the impact of extreme storms on coastal protection structures is a very important function of saltmarshes. Field measurements of wave attenuation over saltmarshes under extreme conditions are rarely available, but experiments in large wave flumes and numerical model simulations provide consistent estimates – for example wave height reduction on the order of 0.5 % per meter saltmarsh width for 1 m significant wave height at the marsh edge and 2 m water depth above the marsh platform<ref>Moller, I., Kudella, M, Rupprecht, F., Spencer, T., Paul, M., van Wesenbeeck, B. K., Wolters, G, Jensen, K., Bouma, T. J., Miranda-Lange, M. and Schimmels, S. 2014. Wave attenuation over coastal saltmarshes under storm surge conditions. Nature Geoscience 7: 727–731 </ref><ref>Garzon, J.L., Maza, M., Ferreira, C.M., Lara, J.L. and Losada, I.J. 2019. Wave Attenuation by Spartina Saltmarshes in the Chesapeake Bay Under Storm Surge Conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124: 5220-5243</ref>. A 100 m wide marsh in front of a sea dike can thus reduce the height of storm waves by about 50%. These studies also show that vegetated saltmarshes (with ''Elymus athericus, Puccinellia maritima, Atriplex prostrata, Spartina alterniflora'') dissipate wave energy much more efficiently than bare tidal flats. | ||

| − | + | Soils with a high percentage of fine soft sediments (clay, organic material) cannot bear much weight. Sea dikes built on such soils cannot therefore be raised to great heights. In this case, a saltmarsh in front of the dike can offer equivalent protection with less stringent conditions for the dike design<ref>Zhang, M., Dai, Z., Bouma, T.J., Bricker, J., Townend, I., Wen, J., Zhao, T. and Cai, H. 2021. Tidal-flat reclamation aggravates potential risk from storm impacts. Coastal Engineering 166: 103868</ref>. However, when previously reclaimed saltmarshes are restored, they may not be as efficient storm surge attenuators as the original saltmarsh; restoration or construction of saltmarshes requires thorough knowledge of natural marsh development<ref>Kiesel, J., Schuerch, M., Moller, I., Spencer, T. and Vafeidis, A. 2019. Attenuation of high water levels over restored saltmarshes can be limited. Insights from Freiston Shore, Lincolnshire, UK. Ecological Engineering 136: 89–100</ref>. A more complete introduction to the coastal protection function of saltmarshes is given in the article [[Nature-based shore protection]]. | |

| − | + | Saltmarshes provide many other [[ecosystem services]]: | |

| − | + | *Coastline stabilization. Saltmarshes are efficient sediment traps; in this way they help stabilizing the coastline. | |

| − | + | *Water quality. Saltmarshes improve the water quality by filtering water and retaining excess nutrients, toxic chemicals and disease-causing organisms. They remove nitrates and phosphates from rivers and streams which receive wastewater effluents. | |

| − | + | *Water supply regulation by recharge and discharge of groundwater. | |

| − | + | *Habitat function. Saltmarshes offer nursery grounds and shelter for larvae and other small organisms and provide food and nesting areas for wading birds and other organisms. Saltmarshes are an important habitat as feeding grounds, nursery areas, spawning areas for many fish species. Commercial landings in the north-east Atlantic region depend to a large extent on these habitats<ref>Seitz, R. D., Wennhage, H., Bergstrom, U., Lipcius, R. N. and Ysebaert, T. 2014. Ecological value of coastal habitats for commercially and ecologically important species. ICES Journal of Marine Science 71: 648–655</ref>. | |

| − | + | *Carbon sequestration, see [[Blue carbon sequestration]]. | |

==Fauna== | ==Fauna== | ||

| + | Saltmarshes are home to many small mammals, small fishes, birds, insects, spiders and marine invertebrates. Marine invertebrates, organisms larger than 0.5 mm, also called macrofauna, include burrowing crabs, polychaete worms, bivalves, mussels, gastropods, amphipods, isopods, and grass shrimps. They occupy various ecological niches and drive key ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, and trophic interactions, directly influencing carbon sequestration, soil quality, and productivity<ref name=B25>Bhuiyan, M.K.A., Godoy, O., Gonzalez-Ortegon, E., Billah, M.M. and Rodil, I.F. 2025. Salt marsh macrofauna: An overview of functions and services. Marine Environmental Research 205, 106975</ref>. Through bioturbation they disturb and mix the sediment layers, redistribute soil nutrients by transporting materials from deeper sediment layers to the surface, enhance sediment aeration and water infiltration, improve soil structure and promote the growth of salt-tolerant vegetation, which in turn fosters greater primary productivity of the ecosystem. Additionally, macrofauna accelerates nutrient recycling by breaking down organic matter and releasing nitrogen and phosphorus. Crab burrows create oxygenated microhabitats fostering nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria and enhancing N<sub>2</sub>O production via ammonia oxidation and denitrification<ref>An, Z., Zheng, Y., Hou, L., Gao, D., Chen, F., Zhou, J., Liu, B., Wu, L., Qi, L., Yin, G. and Liu, M. 2022. Aggravation of nitrous oxide emissions driven by burrowing crab activities in intertidal marsh soils: mechanisms and environmental implications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 171, 108732</ref>. Although microbial mineralization and nutrient cycling under aerobic conditions leads to greater release of greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO<sub>2</sub>), methane (CH<sub>4</sub>) and nitrous oxide (N<sub>2</sub>O) than under anaerobic conditions, bioturbation stimulates plant growth and increases capture and storage of carbon in plant biomass and roots. Additionally, sediment mixing by macrofauna facilitates the formation of soil aggregates, which protect organic matter from rapid decomposition and mobilize carbon in sediments. Oxygenation of sediments further supports diverse microbial communities that transforms organic matter into stable forms of soil organic carbon, promoting long-term carbon storage<ref name=B25/>. | ||

| − | + | Larger crustaceans, such as the blue crab (''Callinectes sapidus'') and the green crab (''Carcinus maenas''), play vital roles as predators and utilize saltmarshes as feeding and nursery grounds. | |

| − | + | Small fishes that dwell in the waters of the saltmarshes, such as sticklebacks, silversides, mummichogs, eels and flounders, link marsh and marine food webs as prey for birds and larger fish. Other fish, such as Gulf killifish, striped killifish and striped blenny, also support marsh food webs by preying on small invertebrates and providing energy transfer to higher trophic levels. Saltmarshes are important breeding, feeding and overwintering grounds for waterfowl. These waterfowl consist of ducks, herons, sharptailed sparrows, Eurasian oystercatchers, reed bunting, etc. In Saudi Arabia, saltmarshes are grazing places for wild dromedaries. | |

| − | |||

| − | In Saudi Arabia, | ||

| + | Although the local diversity of plants and animals found in saltmarshes is comparatively low, the abundance of organisms that do occur in marshes is very high. The abundance per square meter of one species of fiddler crab or snail can reach 100–400 individuals, at times over 1000, and over larger spatial scales the density of one species of non-insect invertebrate (mussels, crabs and snails) can often reach 50,000,000 per square kilometer<ref name=S14/>. | ||

| − | < | + | Given their essential roles in nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, and trophic interactions, macrofaunal communities are reliable indicators of restored marsh functionality and resilience. The presence of diverse and functionally significant groups, such as crabs, polychaetes, and bivalves, often signals the successful restoration of key ecosystem processes<ref>Rezek, R.J., Lebreton, B., Sterba-Boatwright, B. and Beseres Pollack, J. 2017. Ecological structure and function in a restored versus natural saltmarsh. PLoS One 12, e0189871</ref>. These species drive ecological functions that support marsh plant recovery and help restore vital ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration and habitat provision for higher trophic levels<ref name=B25/>. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Freshwater tidal marshes have a high biodiversity but do not harbor many endemic species<ref> Barendregt, A., Whigham, D.F., Meire, P., Baldwin, A.H., Van Damme, S. 2006. Wetlands in the Tidal Freshwater Zone. In: Bobbink R., Beltman B., Verhoeven J.T.A., Whigham D.F. (eds) Wetlands: Functioning, Biodiversity Conservation, and Restoration. Ecological Studies (Analysis and Synthesis), vol 191. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.</ref>. Organisms typical of freshwater tidal marshes are boatmen, flies, mosquitoes and snails. There are also mollusks, ducks, geese, muskrats, raccoons, mink and other small mammals. Some species are seasonal visitors. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| border="0" align="center" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:Haematopus ostralegus M. Decleer.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Eurasian oystercatcher. Photo credit M. Decleer]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:water boatman E.S.Ross.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Water boatman. Photo credit E.S. Ross]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:Mink.jpg|thumb|left|200px|European mink <ref>http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mink</ref>]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

==Threats== | ==Threats== | ||

| − | The total number and area of | + | The total number and area of marshes has been declining for many years. The main cause is embanking, which deprives the saltmarsh habitat of tidal inundation. This normally occurs in areas where the soil level is high enough and the area large enough for embankment to take place. The saltmarsh is destroyed when converted to other uses, notably conversion to intensive agriculture. Embanking leads to additional marsh loss under sea level rise, as it prevents the saltmarsh from shifting landward (so-called [[coastal squeeze]]). |

| − | + | In south east England and in France a special type of embanked saltmarshes exist that are protected as a semi-natural habitat. Once enclosed, the saltmarsh still has salt water inlets with creeks and other unaltered features. Dispersed grazing or cropping for hay are often the only uses and with traditional management it develops into a wildlife habitat of some significance. The term [[Coastal grazing marsh]] (in France: prairie subhalophile) is used to describe this habitat. | |

| − | * Over-grazing | + | Climate change threatens saltmarshes in several ways<ref>Fagherazzi, S., Mariotti, G., Leonardi, N., Canestrelli, A., Nardin, W. and Kearney, W.S. 2019. Saltmarsh Dynamics in a Period of Accelerated Sea Level Rise. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 125, e2019JF005200</ref>. Many marsh plants have a limited tolerance to high temperatures. The high marsh is sensitive to intense drought, causing salinity stress. Because marshes are efficient sediment traps, they can keep up with sea level rise in estuaries with abundant supply of fine sediment. However, there is a limit that depends on the amount and continuity of sediment supply and the rate of sea level rise. Macrotidal conditions are more favorable than microtidal conditions. Sea level rise exacerbates marsh cliff erosion through increased impact of waves and currents. Marsh inundation and waterlogging inhibits vegetation growth. Primary production adds organic material that contributes to raising the marsh soil (up to a few mm/yr <ref>Morris, J. T., Barber, D. C., Callaway, J. C., Chambers, R., Hagen, S. C., Hopkinson, C. S., Johnson, B.J., Megonigal, P., Neubauer, S.C., Troxler, T. and Wigand, C. 2016. Contributions of organic and inorganic matter to sediment volume and accretion in tidal wetlands at steady state. Earths Future 4: 110–121</ref>), but current sea level rise is rising faster. |

| − | * | + | |

| − | + | Reclamation for harbor development and other infrastructures completely destroys the habitat and with it any opportunities for restoration. Areas outside the reclaimed zones still can produce new marshes if there is sufficient supply of new sediment and conditions suitable for growth of new plants. <ref>Council of Europe – Dijkema K.S. et al. 1984. Saltmarshes in Europe. Nature and environment series No.30 p. 178</ref> However, climate change and the associated sea level rise are diminishing the opportunities for saltmarsh development and the [[coastal squeeze]] process takes place in many areas, especially around the southern North Sea <ref>Doody, J.P. 2004. Coastal squeeze - an historical perspective. Journal of Coastal Conservation 10: 129-138</ref>. | |

| + | |||

| + | Other threats include: | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Over-grazing (especially farm animals, but also grazing by wild geese, crabs and snails) | ||

| + | * Eutrophication by agricultural effluents, which makes saltmarshes more susceptible to erosion by increasing microbial decomposition of organic soil material<ref>Fagherazzi, S., FitzGerald, D.M., Fulweiler, R.W., Hughes, Z., Wiberg, P.L., McGlathery, K.J., Morris, J.T., Tolhurst, T.J., Deegan, L.A., Johnson, D.S., Lesser, J.S. and Nelson, J.A. 2022. Ecogeomorphology of Saltmarshes. Ch. 8.14 of Treatise on Geomorphology (ed. Shroder, J.F.), Elsevier</ref> | ||

* Urbanization | * Urbanization | ||

* Recreation | * Recreation | ||

* [[Coast erosion|Coastal erosion]] | * [[Coast erosion|Coastal erosion]] | ||

| − | * | + | * Industrial pollution and waste water |

| − | * | + | * Altered hydrologic regimes |

| + | * Species invasions (especially invasion of ''Spartina anglica'' and ''Erytrigia'' in eutrophic saltmarshes) | ||

| − | ==Case-study: Land van Saeftinghe== | + | ==Case-study: Land van Saeftinghe<ref>https://www.saeftinghe.eu/nl/</ref>== |

| − | The tidal area ‘Drowned land of Saeftinghe’ (Verdronken land van Saeftinghe) is located | + | The [[Tide|tidal]] area ‘Drowned land of Saeftinghe’ (Verdronken land van Saeftinghe) is located near the border between the Netherlands and Belgium, a few kilometers downstream Antwerp in the estuary of the Western Scheldt. It is an official nature reserve since 1976. Because of this legal protection, permits are compulsary for every intervention and strict entrance restrictions are applied. |

| − | The land is | + | The land is situated at the transition zone of the Western Scheldt where the river Scheldt meets the saline North Sea water. Before the storm surge of 1570, the land was a fertile polder. The area has a surface of 3,484 hectares. Almost 70 % of the area is overgrown by saltmarsh vegetation. The remaining 30 % consists of [[Tidal flats from space|mud flats]], sandbanks and a network of channels. Each [[tide]], the brackish water overflows a large part of the area. The unique vegetation is fully adapted to this. The area is an ideal breeding, rest and wintering place for huge quantities of birds. Since 1996 it is a special protected area for birds (1979 Directive 79/409/EEC on the conservation of wild birds) of international importance. |

| − | [[ | + | {| border="0" |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:Saefringhe NIOO-CEME.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Land of Saeftinghe.]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[File:gebiedbes-afb-1.gif|thumb|left|400px|Western Scheldt estuary, with the Land of Saeftinghe in green.]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | In the past, a few dikes were created to promote the silting up. The northern dike connects a few | + | In the past, a few dikes were created to promote the silting up. The northern dike connects a few hillocks (artificial elevations of earth) with the dike. These dikes are still recognizable and are used as wandering path. The hillocks were used by shepherds when the [[tide]] became too high. |

| − | The flora | + | The flora consists of approximately 50 wild plant species. [[Algae]] are not abundant in Saeftinghe because there is too little light that penetrates in the water. Organic matter and a lot of silt make the water turbid. Higher plants are more important in this area. One of the most common plants is pickle weed (''Salicornia''), together with other saltmarsh plants such as English scurvy-grass (''Cochlearia anglica'') and common sea-lavender (''Limonium vulgare''). |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Related articles== | ||

| + | :[[Dynamics, threats and management of salt marshes]] | ||

| + | :[[Spatial and temporal variability of salt marshes]] | ||

| + | :[[Biogeomorphology of coastal systems]] | ||

| + | :[[Nature-based shore protection]] | ||

| + | :[[Tidal channel meandering and marsh erosion]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Saltmarsh restoration guide== | ||

| + | |||

| + | For information of the management and restoration of saltmarshes in the UK see [https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/290974/scho0307bmkh-e-e.pdf DEFRA Saltmarsh management manual] | ||

| + | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 125: | Line 234: | ||

{{author | {{author | ||

| − | |AuthorID= | + | |AuthorID=16323 |

|AuthorFullName=TÖPKE, Katrien | |AuthorFullName=TÖPKE, Katrien | ||

|AuthorName=Ktopke}} | |AuthorName=Ktopke}} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | |

| − | [[Category: | + | {{Review |

| − | [[Category: | + | |name=Pat Doody|AuthorID=7584| |

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Review | ||

| + | |name=Job Dronkers|AuthorID=120| | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Coastal and marine habitats]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Coastal and marine ecosystems]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Salt marshes]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:43, 24 August 2025

This article describes the habitat of salt marshes or saltmarshes (the notation used in this article). It gives an introduction to the characteristics, distribution, evolution, adaptations, zonation, succession, biota, functions and threats of the organisms that live in saltmarshes.

Contents

Introduction

Saltmarshes are defined as natural or semi-natural terrestrial halophytic ecosystems that occur in the intertidal zone between the land and the sea and that are covered by salty or brackish water for part of the time. They can be considered, in some way, as the analogue of mangroves in temperate and arctic regions. The dominant flora is composed of halophytic plants such as grasses, shrubs and herbs. The flora is locally rather species poor, but the global species diversity is high, with over 500 saltmarsh plant species known[1]. Saltmarshes are normally associated with mud flats but also occur on sand flats. These mud flats are sometimes dominated by algae and covered with algal mats. They are periodically flooded by the tide, the height of which can vary from several centimetres in enclosed seas (such as the Baltic Sea) to several metres in open bays, estuaries and tidal lagoons. A network of meandering tidal creeks ensures the drainage of seawater. Through these channels, sediments, detritus, dissolved nutrients, plankton and small fishes are flushed in and out the saltmarshes.

Distribution

Saltmarshes are ubiquitous in estuarine systems in temperate zones all over the world. They seldom occur on open coasts, because the development is inhibited by strong wave action. Although sediment is a prerequisite for their growth in height and width, saltmarsh communities can develop in areas with limited or no sediment supply. Examples include seawater-drenched cliffs and slopes on exposed coasts, at the head of sea lochs and rocky beaches (Doody 2008[2]). The most extensive development of saltmarshes occurs in estuaries with a moderate climate, large tidal range, abundant fine-grained sediments and sheltered locations where particles can settle out of the water column. Globally, saltmarshes are most extensive along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of North America (~40% of the shoreline), the European Atlantic coasts (~25%), the Mediterranean Sea (~9%), and Australia (~25%), with Eastern Asia (especially Russia, China, Korea, and Japan) also hosting marsh coverage comparable to that of Australia.

Saltmarsh evolution

Saltmarshes evolve over time from young marshes to old marshes. At the time that the marsh surface builds up above the high water level, high marsh species invade, outcompete and replace the low marsh plants. The most stress-tolerant plant species occupy the lower reaches of the marshes while less specialized competitive species occupy the upper elevations that are less stressful[1]. Deposition of fine sand and mud raises the marsh to the highest tidal water levels. The marsh then becomes dry land almost disconnected from ocean influences[4]. A cliff develops at the seaward edge of old marshes. Little water flows through the tidal channels of these high marshes. Lateral channel migration and wave attack at the base of marsh cliffs are the main mechanisms for erosion of mature saltmarshes and their subsequent rejuvenation cycle[5][6], see Tidal channel meandering and marsh erosion.

Requirements for development

The requirements for development of saltmarshes are:

- They need supply of fine-grained sediments.

- They must be sheltered from strong waves.

- They need salty (but not hypersaline) conditions to grow. They are halotolerant and have adaptations to these conditions.

- They need a temperate or cool temperature. Incidental freezing temperatures are not damaging the plants.

- They need a tidal range. This is important because it limits the erosion, makes deposition of sediments possible and causes a well-marked zonation.

Saltmarsh zonation

Based on the topography and characteristic plant assemblages, saltmarshes are classified as low, medium and high marshes. This classification is related to the number of tidal submergences per year (Adam 1990[7]). The young, lower marsh is regularly inundated by salt water and vegetation is restricted to pioneer genera such as Salicorna, Suaeda, Aster and Spartina. The middle marsh typically is typically situated in the zone between the mean and spring high tidal levels. The low and middle marshes are drained by tidal creeks that convey flood and ebb flow; ebb flow generally dominates because flood water also inundates the marsh directly from the main channels. When the rising tide exceeds the capacity of the creeks, the overspilling waters deposit the coarse fraction of the sediment load near the channel margins, leading to the development of creek levees[8]. In warm climates and with inadequate drainage, evaporation can raise the salinity of the middle marsh[9]. Middle marshes with higher salinity are vegetated by more salt-tolerant flora. Salt accumulation can also lead to the development of bare areas known as salt pans. The high marsh extends from the mean spring high water level to the highest springtide level. Flooded only by the highest tides and during storms, the high marsh is more like a terrestrial than a true marine environment. In coastal areas with sufficient freshwater infiltration, rainfall, and high groundwater levels, the salinity decreases from the middle to the upper saltmarsh, where a range of floristically diverse wetland communities can develop[10]. Typical high marsh species are cordgrass Spartina patens, spike grass Distichlis spicata and species such as saltwort Salsola and seablite Suaeda. To successfully establish, annual species depend on yearly seed recruitment. Perennial species also benefit from establishment by seeds to colonize new areas. Conditions favorable for germination include a minimum bed level, where disturbance by wave and currents is low, and reduced soil salinity, for example through precipitation[11].

Succession

Succession is the successive development in time of different vegetation types at one place. It is a complex process; the factors determining zonation and succession in saltmarshes are discussed more in detail in Adam (1990[7], pages 49-57), Gray (1992[12]) and Packham & Willis (1997, pages 107-114 [13]).

Biofilm of unicellular algae [14] |

Fixation of the sediment by blue-green and green algae [14] |

Mudflat colonization starts with unicellular algae such as diatoms sticking the sand together by production of mucus. This causes a brownish biofilm on the substrate.

After this stage, filamentous algae contribute to the further fixation of sediments. These algae are mostly blue-green algae, Cyanophyta and Chlorophyta. Small gastropods can feed and develop in huge quantities on it. Locally, the filamentous alga Vaucheria can form banquettes or elevations. Brown algae can be associated with this stage.

A next stage is the germination of species such as the glasswort Salicornia. The seeds germinate after partial desalination of the soil by rain. Sedimentation between and around the glassworts contributes to elevating and stabilizing the substrate. Other species such as Spartina maritima and Spartina anglica compete for the same place. S. maritima is an indigenous species of continental Europe and S. anglica is imported from the British Islands. The hybridisation and invasion of "Spartina" spp is a worldwide phenomenon[15].

Initial plant colonizers play an important role in the recovery of saltmarsh vegetation from disturbance events. They provide shading of the substrate of bare areas and reduce salt accumulation in the soils and thereby facilitate colonization by many other plant species[1].

Saltmarsh vegetation

In Europe, typical vegetation pattern includes a pioneer zone with a sparse cover of Spartina anglica and Salicornia dolichostachya/fragilis. Landward, Puccinellia maritima appears as small clones, and a middle marsh establishes with higher vegetation cover and diversity. Aster tripolium, Cochlearia danica, Salicornia ramosissima, Suaeda maritima, Halimione portulacoides, Plantago maritima, Limonium vulgare, Bostrychia scorpiodes and Atriplex portulacoides may also appear in this zone, whereas Festuca rubra, Juncus gerardii and Elymus athericus are common dominants in the upper marsh. Elymus invasions are facilitated by enrichment of water by nitrogenous compounds.

In southern Europe, typical saltmarsh communities include species such as Sarcocornia fruticosa and Arthrocnemum macrostachyum on the low marsh, Limonium virgatum, Limonium girardianum, Frankenia pulverulenta and Artemisia galla on the middle marsh, and Juncus spp. and other low shrubby species on the high marsh[10].

In eastern North America, dense tall stands of Spartina alterniflora grow in the lower intertidal zone, whereas in contrast, vegetation of European saltmarshes is typically confined to the upper intertidal zone. At higher elevations, marshes are dominated by Spartina patens. Larger marshes in the Gulf of Maine are more likely to have waterlogged pans, comprising forbs such as Agalinis maritima, Atriplex patula, Glaux maritima, Limonium nashii, Plantago maritima, Salicornia europaea, Suaeda linearis, and Triglochin maritima. South of the Chesapeake Bay to northern Florida, Spartina alterniflora dominates extensive intertidal low marshes that cover most of the coastal marsh area. Spartina alterniflora marshes along the Coastal Plain have undergone extensive diebacks, characterized by the premature browning of this species. Spartina alterniflora has invaded many saltmarshes along the Pacific coast. of North America. Spartina foliosa is the only cordgrass species native to the Pacific coast of North America, from Humboldt Bay to Baja California[10].

In China, the endemic Scirpus mariqueter marsh vegetation has been largely replaced by Spartina alterniflora, that has also invaded originally bare mudflats and coastal wetlands with Phragmites australis and Suaeda salsa[16].

Monospecific stands of Spartina alterniflora also dominate the coastal wetlands from southern Brazil to the coastal plain southward from the Río de la Plata Estuary. At higher elevations within this humid region, the middle saltmarshes are dominated by mixed and monospecific stands of the southern cordgrass Spartina densiflora[17].

Adaptations

Plants and animals living in the low and middle saltmarsh must have adaptations to deal with the harsh physical stressors found in this intertidal habitat, including high salt concentrations, intense heat, and low oxygen in waterlogged soils. Some typical adaptations are discussed below.

The saline environment causes waterstress. Plants have to take up water against the osmotic pressure. To overcome the negative osmotic pressure, they generate a negative hydrostatic pressure (by transpiration processes). They have thin, fleshy leaves and are sensitive to extra stress such as pollution. Anatomically, the plants are adapted through strong lignification, a well-developed epidermis and succulent leaves and stems. Evaporation can be limited by thin leaves with scale-like hairs. Physiologically, plants are adapted by accumulating salt in their tissues. In this way, normal osmosis is possible. Other plants have salt gland cells on the lower surface of the leaves and excrete the salt from its tissue.

Saltmarsh plants have to deal with an anoxic environment. The tissue of the plants requires oxygen for respiration. Gas diffusion between sediment particles only occurs in soils that are not waterlogged. Even when the surface water is saturated with oxygen, its concentration in the soil is too low because of the slow oxygen diffusion. Many saltmarsh plants can temporarily cope with low soil oxygen levels by shunting oxygen down to their roots through straw-like vascular tissue called aerenchyma. Roots are superficial systems because of the anoxic sediments. They consist of perennial thick roots with a corky layer and without root hairs. To fix the substrate, short-lived, thin and highly branched roots are developed with numerous root hairs to absorb nutrients.

Nitrogen limitation can also play a role in the development of saltmarsh vegetation, even though nitrogen levels can be very high. The reason is that concentrations of sulfide and sodium ions are often high too and interfere with nitrogen uptake by plants[1].

Saltmarsh plants do not tolerate permanent waterlogging. Such conditions exist in depressions of flat, poorly drained marsh areas, where marsh ponds form. These ponds are filled with stagnant anoxic water where collapse of peat soil is caused by microbial mineralization of organic matter[19].

Functions

Attenuating the impact of extreme storms on coastal protection structures is a very important function of saltmarshes. Field measurements of wave attenuation over saltmarshes under extreme conditions are rarely available, but experiments in large wave flumes and numerical model simulations provide consistent estimates – for example wave height reduction on the order of 0.5 % per meter saltmarsh width for 1 m significant wave height at the marsh edge and 2 m water depth above the marsh platform[20][21]. A 100 m wide marsh in front of a sea dike can thus reduce the height of storm waves by about 50%. These studies also show that vegetated saltmarshes (with Elymus athericus, Puccinellia maritima, Atriplex prostrata, Spartina alterniflora) dissipate wave energy much more efficiently than bare tidal flats.

Soils with a high percentage of fine soft sediments (clay, organic material) cannot bear much weight. Sea dikes built on such soils cannot therefore be raised to great heights. In this case, a saltmarsh in front of the dike can offer equivalent protection with less stringent conditions for the dike design[22]. However, when previously reclaimed saltmarshes are restored, they may not be as efficient storm surge attenuators as the original saltmarsh; restoration or construction of saltmarshes requires thorough knowledge of natural marsh development[23]. A more complete introduction to the coastal protection function of saltmarshes is given in the article Nature-based shore protection.

Saltmarshes provide many other ecosystem services:

- Coastline stabilization. Saltmarshes are efficient sediment traps; in this way they help stabilizing the coastline.

- Water quality. Saltmarshes improve the water quality by filtering water and retaining excess nutrients, toxic chemicals and disease-causing organisms. They remove nitrates and phosphates from rivers and streams which receive wastewater effluents.

- Water supply regulation by recharge and discharge of groundwater.

- Habitat function. Saltmarshes offer nursery grounds and shelter for larvae and other small organisms and provide food and nesting areas for wading birds and other organisms. Saltmarshes are an important habitat as feeding grounds, nursery areas, spawning areas for many fish species. Commercial landings in the north-east Atlantic region depend to a large extent on these habitats[24].

- Carbon sequestration, see Blue carbon sequestration.

Fauna

Saltmarshes are home to many small mammals, small fishes, birds, insects, spiders and marine invertebrates. Marine invertebrates, organisms larger than 0.5 mm, also called macrofauna, include burrowing crabs, polychaete worms, bivalves, mussels, gastropods, amphipods, isopods, and grass shrimps. They occupy various ecological niches and drive key ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, and trophic interactions, directly influencing carbon sequestration, soil quality, and productivity[25]. Through bioturbation they disturb and mix the sediment layers, redistribute soil nutrients by transporting materials from deeper sediment layers to the surface, enhance sediment aeration and water infiltration, improve soil structure and promote the growth of salt-tolerant vegetation, which in turn fosters greater primary productivity of the ecosystem. Additionally, macrofauna accelerates nutrient recycling by breaking down organic matter and releasing nitrogen and phosphorus. Crab burrows create oxygenated microhabitats fostering nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria and enhancing N2O production via ammonia oxidation and denitrification[26]. Although microbial mineralization and nutrient cycling under aerobic conditions leads to greater release of greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) than under anaerobic conditions, bioturbation stimulates plant growth and increases capture and storage of carbon in plant biomass and roots. Additionally, sediment mixing by macrofauna facilitates the formation of soil aggregates, which protect organic matter from rapid decomposition and mobilize carbon in sediments. Oxygenation of sediments further supports diverse microbial communities that transforms organic matter into stable forms of soil organic carbon, promoting long-term carbon storage[25].

Larger crustaceans, such as the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) and the green crab (Carcinus maenas), play vital roles as predators and utilize saltmarshes as feeding and nursery grounds. Small fishes that dwell in the waters of the saltmarshes, such as sticklebacks, silversides, mummichogs, eels and flounders, link marsh and marine food webs as prey for birds and larger fish. Other fish, such as Gulf killifish, striped killifish and striped blenny, also support marsh food webs by preying on small invertebrates and providing energy transfer to higher trophic levels. Saltmarshes are important breeding, feeding and overwintering grounds for waterfowl. These waterfowl consist of ducks, herons, sharptailed sparrows, Eurasian oystercatchers, reed bunting, etc. In Saudi Arabia, saltmarshes are grazing places for wild dromedaries.

Although the local diversity of plants and animals found in saltmarshes is comparatively low, the abundance of organisms that do occur in marshes is very high. The abundance per square meter of one species of fiddler crab or snail can reach 100–400 individuals, at times over 1000, and over larger spatial scales the density of one species of non-insect invertebrate (mussels, crabs and snails) can often reach 50,000,000 per square kilometer[1].

Given their essential roles in nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, and trophic interactions, macrofaunal communities are reliable indicators of restored marsh functionality and resilience. The presence of diverse and functionally significant groups, such as crabs, polychaetes, and bivalves, often signals the successful restoration of key ecosystem processes[27]. These species drive ecological functions that support marsh plant recovery and help restore vital ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration and habitat provision for higher trophic levels[25].

Freshwater tidal marshes have a high biodiversity but do not harbor many endemic species[28]. Organisms typical of freshwater tidal marshes are boatmen, flies, mosquitoes and snails. There are also mollusks, ducks, geese, muskrats, raccoons, mink and other small mammals. Some species are seasonal visitors.

European mink [29] |

Threats

The total number and area of marshes has been declining for many years. The main cause is embanking, which deprives the saltmarsh habitat of tidal inundation. This normally occurs in areas where the soil level is high enough and the area large enough for embankment to take place. The saltmarsh is destroyed when converted to other uses, notably conversion to intensive agriculture. Embanking leads to additional marsh loss under sea level rise, as it prevents the saltmarsh from shifting landward (so-called coastal squeeze).

In south east England and in France a special type of embanked saltmarshes exist that are protected as a semi-natural habitat. Once enclosed, the saltmarsh still has salt water inlets with creeks and other unaltered features. Dispersed grazing or cropping for hay are often the only uses and with traditional management it develops into a wildlife habitat of some significance. The term Coastal grazing marsh (in France: prairie subhalophile) is used to describe this habitat.

Climate change threatens saltmarshes in several ways[30]. Many marsh plants have a limited tolerance to high temperatures. The high marsh is sensitive to intense drought, causing salinity stress. Because marshes are efficient sediment traps, they can keep up with sea level rise in estuaries with abundant supply of fine sediment. However, there is a limit that depends on the amount and continuity of sediment supply and the rate of sea level rise. Macrotidal conditions are more favorable than microtidal conditions. Sea level rise exacerbates marsh cliff erosion through increased impact of waves and currents. Marsh inundation and waterlogging inhibits vegetation growth. Primary production adds organic material that contributes to raising the marsh soil (up to a few mm/yr [31]), but current sea level rise is rising faster.

Reclamation for harbor development and other infrastructures completely destroys the habitat and with it any opportunities for restoration. Areas outside the reclaimed zones still can produce new marshes if there is sufficient supply of new sediment and conditions suitable for growth of new plants. [32] However, climate change and the associated sea level rise are diminishing the opportunities for saltmarsh development and the coastal squeeze process takes place in many areas, especially around the southern North Sea [33].

Other threats include:

- Over-grazing (especially farm animals, but also grazing by wild geese, crabs and snails)

- Eutrophication by agricultural effluents, which makes saltmarshes more susceptible to erosion by increasing microbial decomposition of organic soil material[34]

- Urbanization

- Recreation

- Coastal erosion

- Industrial pollution and waste water

- Altered hydrologic regimes

- Species invasions (especially invasion of Spartina anglica and Erytrigia in eutrophic saltmarshes)

Case-study: Land van Saeftinghe[35]

The tidal area ‘Drowned land of Saeftinghe’ (Verdronken land van Saeftinghe) is located near the border between the Netherlands and Belgium, a few kilometers downstream Antwerp in the estuary of the Western Scheldt. It is an official nature reserve since 1976. Because of this legal protection, permits are compulsary for every intervention and strict entrance restrictions are applied. The land is situated at the transition zone of the Western Scheldt where the river Scheldt meets the saline North Sea water. Before the storm surge of 1570, the land was a fertile polder. The area has a surface of 3,484 hectares. Almost 70 % of the area is overgrown by saltmarsh vegetation. The remaining 30 % consists of mud flats, sandbanks and a network of channels. Each tide, the brackish water overflows a large part of the area. The unique vegetation is fully adapted to this. The area is an ideal breeding, rest and wintering place for huge quantities of birds. Since 1996 it is a special protected area for birds (1979 Directive 79/409/EEC on the conservation of wild birds) of international importance.

In the past, a few dikes were created to promote the silting up. The northern dike connects a few hillocks (artificial elevations of earth) with the dike. These dikes are still recognizable and are used as wandering path. The hillocks were used by shepherds when the tide became too high.

The flora consists of approximately 50 wild plant species. Algae are not abundant in Saeftinghe because there is too little light that penetrates in the water. Organic matter and a lot of silt make the water turbid. Higher plants are more important in this area. One of the most common plants is pickle weed (Salicornia), together with other saltmarsh plants such as English scurvy-grass (Cochlearia anglica) and common sea-lavender (Limonium vulgare).

Related articles

- Dynamics, threats and management of salt marshes

- Spatial and temporal variability of salt marshes

- Biogeomorphology of coastal systems

- Nature-based shore protection

- Tidal channel meandering and marsh erosion

Saltmarsh restoration guide

For information of the management and restoration of saltmarshes in the UK see DEFRA Saltmarsh management manual

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Silliman, B.R. 2014. Saltmarshes. Current Biology 24(9) R348

- ↑ Doody, J.P. 2008. Saltmarsh Conservation, Management and Restoration. Coastal Systems and Continental Margins, Volume 12, Springer, 217 pp.

- ↑ Mcowen, C., Weatherdon, L.V., Bochove, J., Sullivan, E., Blyth, S., Zockler, C., Stanwell-Smith, D., Kingston, N., Martin, C.S., Spalding, M. and Fletcher, S. 2017. A global map of saltmarshes (v6.1). Biodiversity Data Journal 5: e11764. Paper DOI: https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.5.e11764

- ↑ Pinet P.R. 1998. Invitation to Oceanography. Jones and Barlett Publishers. p. 508

- ↑ Levoy, F., Anthony, E.J., Dronkers, J., Monfort, O. and Montreuil, A-L. 2019. Short-term to Decadal-scale Sand Flat Morphodynamics and Sediment Balance of a Megatidal Bay: Insight from Multiple LiDAR Datasets. Journal of Coastal Research SI 88: 61–76

- ↑ Mariotti, G. and Fagherazzi, S. 2013. Critical width of tidal flats triggers marsh collapse in the absence of sea-level rise, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110(14): 5353–5356

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Adam, P., 1990. Saltmarsh Ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- ↑ Temmerman, S., Govers, G., Meire, P. and Wartel, S. 2004. Simulating the long-term development of levee-basin topography of tidal marshes. Geomorphology 63: 39-55

- ↑ Pennings, S.C. and Bertness, M.D. 1999. Using latitudinal variation to examine effects of climate on coastal saltmarsh pattern and process. Current Topics in Wetland Biogeochemistry 3: 100-111

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Pratolongo, P., Leonardi, N., Kirby, J.R. and Plater, A. 2019. Temperate Coastal Wetlands: Morphology, Sediment Processes, and Plant Communities. Chapter 3 in Coastal Wetlands, An Integrated Ecosystem Approach (Second Edition), p. 105-152

- ↑ van Regteren, M., Amptmeijer, D., de Groot, A.V., Baptist, M.J. and Elschot, K. 2020. Where does the saltmarsh start? Field-based evidence for the lack of a transitional area between a gradually sloping intertidal flat and saltmarsh. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 243: 106909

- ↑ Gray, A.J. 1992. Saltmarsh plant ecology. In: Saltmarshes: morphodynamics, conservation and engineering significance, J.R.L., Allen, & K., Pye, eds., 63-79. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- ↑ Packham, J.R. & Willis, A.J., 1997. Ecology of dunes, saltmarsh and shingle. Chapman & Hall, London.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Credit Eric Coppejans - http://www.vliz.be/imis/imis.php?module=person&persid=134

- ↑ Strong, D.R. and Ayres, D.R. 2013. Ecological and Evolutionary Misadventures of Spartina. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 44: 23.1–23.22

- ↑ Gao, S., Du, Y., Xie, W., Gao, W., Wang, D. and Wu, X. 2014. Environment-ecosystem dynamic processes of Spartina alterniflora salt-marshes along the eastern China coastlines. Science China Earth Sciences 57: 2567-2586

- ↑ Costa, C.S.B., Marangoni, J.C. and Azevedo, A.M.G. 2003. Plant zonation in irregularly flooded salt marshes: relative importance of stress tolerance and biological interactions. Journal of Ecology 91: 951-965

- ↑ Himmelstein, J., Vinent, O.D., Temmerman, S. and Kirwan, M.L. 2021. Mechanisms of Pond Expansion in a Rapidly Submerging Marsh. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:704768

- ↑ Hutchings, A.M., Antler. G., Wilkening, J.V., Basu, A., Bradbury, H.J., Clegg, J.A., Gorka, M., Lin, C.Y., Mills, J.V., Pellerin, A., Redeker, K.R., Sun, X. and Turchyn, A.V. 2019. Creek Dynamics Determine Pond Subsurface Geochemical Heterogeneity in East Anglian (UK) Salt Marshes. Front. Earth Sci. 7: 41

- ↑ Moller, I., Kudella, M, Rupprecht, F., Spencer, T., Paul, M., van Wesenbeeck, B. K., Wolters, G, Jensen, K., Bouma, T. J., Miranda-Lange, M. and Schimmels, S. 2014. Wave attenuation over coastal saltmarshes under storm surge conditions. Nature Geoscience 7: 727–731

- ↑ Garzon, J.L., Maza, M., Ferreira, C.M., Lara, J.L. and Losada, I.J. 2019. Wave Attenuation by Spartina Saltmarshes in the Chesapeake Bay Under Storm Surge Conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124: 5220-5243

- ↑ Zhang, M., Dai, Z., Bouma, T.J., Bricker, J., Townend, I., Wen, J., Zhao, T. and Cai, H. 2021. Tidal-flat reclamation aggravates potential risk from storm impacts. Coastal Engineering 166: 103868

- ↑ Kiesel, J., Schuerch, M., Moller, I., Spencer, T. and Vafeidis, A. 2019. Attenuation of high water levels over restored saltmarshes can be limited. Insights from Freiston Shore, Lincolnshire, UK. Ecological Engineering 136: 89–100

- ↑ Seitz, R. D., Wennhage, H., Bergstrom, U., Lipcius, R. N. and Ysebaert, T. 2014. Ecological value of coastal habitats for commercially and ecologically important species. ICES Journal of Marine Science 71: 648–655

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Bhuiyan, M.K.A., Godoy, O., Gonzalez-Ortegon, E., Billah, M.M. and Rodil, I.F. 2025. Salt marsh macrofauna: An overview of functions and services. Marine Environmental Research 205, 106975

- ↑ An, Z., Zheng, Y., Hou, L., Gao, D., Chen, F., Zhou, J., Liu, B., Wu, L., Qi, L., Yin, G. and Liu, M. 2022. Aggravation of nitrous oxide emissions driven by burrowing crab activities in intertidal marsh soils: mechanisms and environmental implications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 171, 108732

- ↑ Rezek, R.J., Lebreton, B., Sterba-Boatwright, B. and Beseres Pollack, J. 2017. Ecological structure and function in a restored versus natural saltmarsh. PLoS One 12, e0189871

- ↑ Barendregt, A., Whigham, D.F., Meire, P., Baldwin, A.H., Van Damme, S. 2006. Wetlands in the Tidal Freshwater Zone. In: Bobbink R., Beltman B., Verhoeven J.T.A., Whigham D.F. (eds) Wetlands: Functioning, Biodiversity Conservation, and Restoration. Ecological Studies (Analysis and Synthesis), vol 191. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mink

- ↑ Fagherazzi, S., Mariotti, G., Leonardi, N., Canestrelli, A., Nardin, W. and Kearney, W.S. 2019. Saltmarsh Dynamics in a Period of Accelerated Sea Level Rise. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface 125, e2019JF005200

- ↑ Morris, J. T., Barber, D. C., Callaway, J. C., Chambers, R., Hagen, S. C., Hopkinson, C. S., Johnson, B.J., Megonigal, P., Neubauer, S.C., Troxler, T. and Wigand, C. 2016. Contributions of organic and inorganic matter to sediment volume and accretion in tidal wetlands at steady state. Earths Future 4: 110–121

- ↑ Council of Europe – Dijkema K.S. et al. 1984. Saltmarshes in Europe. Nature and environment series No.30 p. 178

- ↑ Doody, J.P. 2004. Coastal squeeze - an historical perspective. Journal of Coastal Conservation 10: 129-138

- ↑ Fagherazzi, S., FitzGerald, D.M., Fulweiler, R.W., Hughes, Z., Wiberg, P.L., McGlathery, K.J., Morris, J.T., Tolhurst, T.J., Deegan, L.A., Johnson, D.S., Lesser, J.S. and Nelson, J.A. 2022. Ecogeomorphology of Saltmarshes. Ch. 8.14 of Treatise on Geomorphology (ed. Shroder, J.F.), Elsevier

- ↑ https://www.saeftinghe.eu/nl/

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|