Salinity

Contents

Introduction

| Salinity class | S |

| Hyperhaline | > 65 |

| Metahaline | 45-65 |

| Euhaline | 30-35 |

| Polyhaline | 18-30 |

| Mesohaline | 5-18 |

| Oligohaline | 0.5-5 |

The salinity of seawater is defined as the total amount by weight of dissolved salts in one kilogram of seawater. Salinity is expressed in the unit g / kg, which is often written as ppt (part per thousand) or ‰ (permil). Salts dissolved in seawater are dissociated into their ions; the predominant ions are chloride and sodium; other significant ions are magnesium, sulfate, calcium and potassium. Over the years, various methods have been developed to determine salinity. The most practical method currently used is through electrical conductivity. Because this is an indirect method, an accurate relationship has been established between conductivity and salinity. The salinity determined in this way is a dimensionless quantity that is called the practical salinity. According to the practical salinity scale, typical 'standard' seawater has a salinity of 35. In order to achieve better consistency with the thermodynamics of seawater, a new salinity scale was introduced in 2010, the so-called absolute salinity scale. The small numerical correction of the practical salinity scale that this entails is not of great practical importance for coastal waters, where it is dwarfed by the strong variability of the salinity in space and time. However, great precision is necessary for the ocean, because small salinity differences can be highly relevant to the large-scale ocean circulation and the characterization of water masses.

Seawater is denser than freshwater because of the added weight of dissolved salts; the relation between salinity and density is dealt with in the article Seawater density. This article gives an overview of the different salinity scales. Sensors used for conductivity measurements are discussed in the article Salinity sensors.

Salinity measurements and definitions throughout history

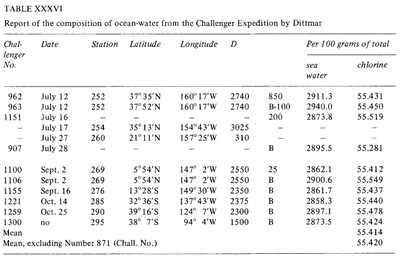

Since as far as Ancient Greece times, attempts have been made to measure the "saltiness" of seawater. However, these early methods were not very efficient and their sensitivity and repeatability were very limited. During the Modern History more precise methodologies were developed: weighing after evaporation (Boyle, 1693[1]; Birch, 1965[2]), solvent extraction (Lavoisier, 1772[3]) and precipitation (Bergman, 1784[4]). In 1865, Forchhammer[5] introduced the term salinity and dedicated himself to measure individual components of seasalt rather than the total salinity. He found that the ratio of major salts in samples of seawater from various locations was constant. This constant ratio is known as Forchhammer's Principle, or the Principle of Constant Proportions. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, William Dittmar[6], following the work of Forchhammer, tested several methods to analyse the salinity and the chemical composition of seawater. The Dittmar methods for chemical analysis of the seawater were extremely precise. Dittmar analysed the chlorine content in seawater using silver nitrate precipitation of the chloride, and compared it with synthetically prepared seawater samples to assess the method's accuracy. He later analysed 77 samples from around the world, taken during the Challenger Expedition and noticed the same constancy of composition observed by Forchhammer: "although the concentration of the waters is very different, the percentage composition of the dissolved material is almost the same in all cases". [7].

| Ion | Na+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | K+ | Sr2+ | Cl- | SO42- | HCO3- | Br- | CO32- | B(OH)4- | F- | OH- | B(OH)3 | CO2 | SUM |

| gram | 10.78145 | 1.28372 | 0.41208 | 0.39910 | 0.00795 | 19.35271 | 2.71235 | 0.10481 | 0.06728 | 0.01434 | 0.00795 | 0.00130 | 0.00014 | 0.01944 | 0.00042 | 35.16504 |

Salinity definition 1902

With more accurate techniques to measure salinity, there was a need to have the same definition of salinity and measuring methods across the scientific community. In 1889, Martin Knudsen was named by ICES to preside a commission to address the salinity issues. He formulated the following definition:

"Salinity is the total amount of solid materials, in grams, dissolved in one kilogram of sea water when all the carbonate has been converted to oxide, the bromine and iodine replaced by chlorine and all organic matter completely oxidized" [9].

Although this definition is correct and served oceanographers for the next 65 years, the methodology is impractical and difficult to carry out with precision. Knowing that the major ions remain in constant proportions to each other and chlorine could be accurately measured by silver volumetric titration, the commission defined "chlorinity" as a measure of salinity. Originally, salinity was calculated from the Cl- content (chlorinity). The chlorinity is measured as the mass in g of halides that can be precipitated from 1,000 g of seawater by Ag+ using a standard AgNO3 solution. The reaction is:

AgNO3 (aq) + NaCl (aq) → AgCl(s) + NaNO3 (aq)

After analyzing a great number of samples from nine locations, Knudsen and his colleagues developed an equation to calculate salinity based on chlorine content:

[math]S = 1.805 \, Cl^- + 0.03 \; g / kg , \qquad (1)[/math]

where chlorinity Cl- is defined as the mass of silver required to precipitate completely the halogens in 0.3285234 kg of the sea-water sample:

Cl- = 328.5234 Ag+

Salinity measurements are sometimes expressed in the chlorinity scale (g Cl- / kg) or in the chlorosity scale (g Cl- / l).

Revised salinity definition 1966

As seen from formula (1), this method has its limitations and is not entirely correct: when chlorinity is 0, salinity is 0.03. Furthermore, Carritt and Carpenter (1959[10]) have estimated that the uncertainty of a computed value of salinity from a measured value of chlorinity using this relation can be as much as 0.04 g / kg. This is due to variations in the chemical composition in some seawater samples (Baltic) and the fact that only 9 different locations were sampled to define chlorinity. In the beginning of the 60's, with the development of conductivity bridges, it became possible to measure salinity with great precision (± 0.003 g / kg). Bridges gave conductivity ratios between the sample and standard seawater used to calibrate the bridges. However the standard seawater had been developed for chlorinity measurements and not for conductivity, so a new conductivity standard was commissioned to the Joint Panel for Oceanographic Tables and Standards (JPOTS). Based on new measurements of salinity, temperature and conductivity from samples around the world, the standing formula of chlorinity was revised to:

[math]S = 1.80655 \, Cl^- . \qquad (2)[/math]

Practical Salinity Scale-1978 / EOS-80

WHAT IS PSU? by Frank J. Millero in Oceanography Magazine, 1993

After receiving the latest issue of Oceanography, I was irritated by the Sea-Bird advertisement on the inside cover. It shows a TS diagram that is labeled with the term PSU. Although I have been unsuccessful in getting the company to discontinue the use of this term, I thought I should write this letter to express my concerns about its use my oceanographers in published articles. The term apparently is used to denote the use of the Practical Salinity Scale and is an abbreviation for Practical Salinity Unit. As a member of the Joint Panel on Oceanographic Tables and Standards that was instrumental in the development of the international equation of the state of seawater and the practical salinity scale, I am amazed that the practice that seems to have been adopted by oceanographers in using PSU. The practical salinity scale was defined as conductivity ratio with no units. A seawater sample with a conductivity ratio of 1.0 at 15ºC with a KCl solution containing a mass of 32.4356 g in a total mass of 1 kg of solution has a salinity of 35.000 (no units or ‰ are needed). The salinity and temperature dependence of this ratio for seawater weight evaporated or diluted with water led to the full definition of the practical salinity scale. This definition was adopted by all the National and International Oceanographic Organizations. It also was published in all the journal publishing oceanographic studies. Somewhere along the line oceanographers started to use the term PSU (practical salinity unit) to indicate that the practical salinity scale was used to determine conductivity salinity. This apparently resulted from the previous use ‰ to represent parts per thousand, which some oceanographers felt was a unit. The bottom line is that salinity has always been a ratio and does not have physical units. The use of the term PSU should not be permitted in the field and certainly not used in published papers. Whenever the practical salinity scale is used to determine salinity this should be stated somewhere in the paper. The use of the term PSS can be used to indicate that the Practical Salinity Scale is used. One certainly does not have to use to term PSU on all figures showing TS data. I should also point out that UNESCO (1985)[11] has published a SUN report that carefully outlines the use of units in the field of oceanography. This report was also adopted by all the International Oceanographic Societies but is not generally used by the oceanographers and the journals publishing oceanographic data. If the field of oceanography is to become a recognized science, it must adopt the units that are basic to the fields of chemistry and physics. It also should not adopt new units for variables that are unitless.

The weight ratio of the various dissolved salts in seawater is almost the same everywhere across the world oceans. This also holds for coastal waters, although deviations from the standard composition become more important at low salinity in the salt-fresh transition zone. Because of the approximately universal composition of the dissolved salts in seawater, seawater salinity can be derived from the degree to which seawater is diluted with fresh water. This is most conveniently done by measuring the conductivity [math]C[/math]. The Practical Salinity Scale (PSS) was introduced to establish a univocal relationship between salinity and conductivity. This relationship is based on the ratio [math]R[/math] of the seawater conductivity and the conductivity [math]C(35,15)[/math] of a standard solution of 1 kg containing 32.4356 g KCl at 15oC, which has salinity [math]S=35[/math].

The relation between salinity [math]S(T)[/math] and conductivity ratio [math]R=R(S,T)[/math] was based on precise determinations of chlorinity and the conductivity ratio for different temperatures [math]T[/math] on 135 natural seawater samples, all collected within 100 m of the surface, and including samples from all oceans and the Baltic, Black, Mediterranean, and Red Seas. After chlorinity was converted to salinity, using the relation (2), the following polynomial was computed by least squares [12]:

[math]S(T) = S(15) + \Delta S(T) , \qquad R=\Large\frac{C(S,T)}{C(35,15)}\normalsize , \qquad (3)[/math]

[math]S(15)=0.008-0.1692\,R^{1/2}+25.3851\,R+14.0941\,R^{3/2}-7.0261\,R^2+2.7081\,R^{5/2} , \qquad (4)[/math]

[math]\Delta S(T)= \Large\frac{T-15}{1+0.0162(T-15)}\normalsize (0.0005-0.0056\,R^{1/2} \\ -0.0066\,R-0.0375\,R^{3/2}+0.0636\,R^2-0.0144\,R^{5/2}) , \qquad (5)[/math]

for [math] 2 \, \le S \le \, 42 [/math] and for atmospheric pressure,

where [math]C(S,T)[/math] is the conductivity of the seawater sample with practical salinity [math]S[/math] and temperature [math]T[/math] (oC). If R=1 we have S=35. If the conductivity [math]C(S,T)[/math] is expressed in in units mS/cm (millisiemens per cm), then [math]C(35,15)[/math] takes the value 42.914. Using this value, the salinity at [math]T=[/math]15oC (Eq. 2) is well approximated by

[math]S(15) \approx 0.586 \, C^{1.0876}[/math] , where [math]C[/math] is expressed in mS/cm.

However, since the absolute conductivity cannot be measured as accurately as required for precise salinity measurements, it is advisable to use the conductivity measured relative to that of standard seawater and to apply the salinity-conductivity relations (3-5).

The Practical Salinity Scale was adopted in 1980 as the international standard for oceanography by the UNESCO/SCOR/ICES/IAPSO Joint Panel on Oceanographic Tables and Standards and SCOR Working Group 51 (JPOTS). The corresponding Equation Of State of Seawater (EOS-80) based on the temperature scale IPTS-68 and on the Practical Salinity Scale 1978, PSS-78 (Lewis and Perkin, 1981[13]) was published by Millero et al. (1980[8]). It should be noted that according to the UNESCO background documents, equations (3-5) may not be valid for water with a chemical composition very different from standard seawater[14]. For estuarine waters it may be necessary to apply a correction to equations (3-5), depending on the mineral composition of the fresh water entering the estuary[15].

TEOS-10

UNESCO's IOC introduced in 2010 a new definition of salinity, the so-called Absolute Salinity [math]S_A[/math]. The Thermodynamic Equation Of State (TEOS) was updated for several reasons [16]:

|

- Several of the polynomial expressions of the International Equation of State of Seawater (EOS-80) are not fully consistent with each other as they do not exactly obey the thermodynamic Maxwell cross-differentiation relations. The new approach eliminates this problem.

- Since the late 1970s a more accurate thermodynamic description of pure water has appeared (IAPWS-95). Also more and rather accurate measurements of the properties of seawater (such as for (i) heat capacity, (ii) sound speed and (iii) the temperature of maximum density) have been made and can be incorporated into a new thermodynamic description of seawater.

- The impact on seawater density of the variation of the composition of seawater in the different ocean basins has become better understood.

- The increasing emphasis on the ocean as being an integral part of the global heat engine points to the need for accurate expressions for the enthalpy and internal energy of seawater so that heat fluxes can be more accurately determined in the ocean (enthalpy and internal energy were not available from EOS-80).

- The temperature scale has been revised from ITS-68 to ITS-90 and the atomic weights of the elements have been revised.

The Absolute Salinity [math]S_A[/math] is defined as the mass fraction of dissolved non‐H2O material in a seawater sample at its temperature and pressure and expressed in units g / kg. Therefore it is also referred to as Density Salinity. The mass fraction of H2O in a seawater sample is thus given by [math]1-0.001 S_A[/math]. This definition addresses correctly the issue 'what constitutes water and what constitutes dissolved material' (for example, the dissolution of a given mass of CO2 in pure water essentially transforms some of the water into dissolved material because it produces a mixture of CO2, H2CO3, HCO3-, CO32-, H+, OH- and H2O, with the relative proportions depending on dissociation constants that depend on temperature, pressure and pH[18].).

The values of the Absolute Salinity [math]S_A[/math] differs only slightly from the corresponding values of the Practical Salinity [math]S[/math]. For seawater of standard reference composition

[math]S_A = \Large\frac{35.16504}{35}\normalsize S \; g / kg \qquad (6)[/math].

In other words, for a reference seawater sample with Practical Salinity 35 the Absolute Salinity is 35.16504 g / kg. For non-standard seawater collected at arbitrary places in the ocean, the average difference between the Absolute Salinity [math]S_A[/math] and Eq. (6) is about 0.0107 g / kg. The value of the Absolute Salinity [math]S_A[/math] expressed in g / kg and the corresponding value of the Practical Salinity [math]S[/math] are known to differ by no more than about 0.5%. Using Practical Salinity has the advantage that it is (almost) directly determined from measurements of conductivity, temperature and pressure, whereas Absolute Salinity is generally derived from a combination of these measurements plus other measurements and correlations that are often not well established.

Biological impact of salinity

The functioning of the cells of living organisms is largely determined by the ability to absorb or excrete certain substances. Osmosis is the process by which substances can pass through the cell membrane. The cell membrane is more permeable to certain substances than to others. For example, water can pass the membrane more easily than salt ions. When species adapted to a low-salinity environment are exposed to high salinities, the salinity of the extracellular fluid in these species may also increase. In this case, osmosis will cause a net loss of cell fluid, causing cells to shrink. In the opposite case of a marine species exposed to a low salinity regime, cells will absorb water and expand. In either case, the species can die. Some species have adaptations that allow them to tolerate changes in the salinity of their environment. To prevent expansion or shrinkage of their cells, these species use different mechanisms to maintain a balance between water and solutes in their body. This is called homeostasis. See the article Osmosis for more details.

Related articles

- Salinity sensors

- Seawater density

- Seawater intrusion and mixing in estuaries

- Estuarine circulation

- Salt wedge estuaries

- Shelf sea exchange with the ocean

References

- ↑ Boyle, R. 1693. An account of the honourable Robert Boyle’s way of examining waters as to freshness and saltness. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. 17: 627-641

- ↑ Birch, T. (ed.) 1965. The works of Robert Boyle. Georg Olms, Hildeschiem, 6 vol.

- ↑ Lavoisier, A. 1772. Memoire sur l’usage de esprit-de-vin dans l’analyse des eaux minerales, Mem. Acad. Roy. Sci. (Paris), 1772, 555-563

- ↑ Bergman, T. 1784. Physical and chemical essays (translated by Edmund Cullen) Murray, London, 2 vol.

- ↑ Forchhammer, G. 1865. On the composition of seawater in different parts of the ocean. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. 155: 203-262

- ↑ Dittmar, I.W. 1884. Dittmar, W., 1884. Report on Researches into the Composition of Ocean-Water, collected by H.M.S.Challenger, during the years 1873-1876. Physics and Chemistry 76,1, 251pp.

- ↑ Wallace, W.J. 1974. The Development of the Chlorinity/Salinity Concept in Oceanography. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 239.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Millero, F. J., Feistel, R., Wright, D.G. and McDougall, T.J. 2008. The composition of Standard Seawater and the definition of the Reference‐Composition Salinity Scale, Deep‐Sea Res. I, 55: 50‐72

- ↑ KNUDSEN, M. 1901. Hydrographical tables. G.E.C. Gad, Copenhagen, 63p

- ↑ Carritt, D. E. and Carpenter, J . H. 1959. The composition of sea water and the salinity-chlorinity-density problems. In Physical and Chemical Properties of Sea Water, pp. 67-86. Nat. Acad. Sci. Pub. 600; 202 pp.

- ↑ UNESCO (1985) The international system of units (SI) in oceanography. UNESCO Technical Papers No.45, IAPSO Pub. Sci. No. 32, Paris, France.

- ↑ Fofonoff, N.P. and Millard, R.C. 1983. Algorithms for computation of fundamental properties of seawater. UNESCO technical papers in marine science 44

- ↑ Lewis, E. L. and Perkin, R. G. 1981. The Practical Salinity Scale 1978: conversion of existing data. Deep-Sea Res. 28A: 307-328

- ↑ UNESCO 1981. Background papers and supporting data on the practical salinity scale 1978. UNESCO Tech. Pap. Mar. Sci., 37

- ↑ Hutton, P.H. and Roy, S.B. 2023. Application of the practical salinity scale to the waters of San Francisco estuary. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 290, 108380

- ↑ IOC, SCOR and IAPSO 2010. The international thermodynamic equation of seawater – 2010: Calculation and use of thermodynamic properties. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Manuals and Guides No. 56, UNESCO, 196 pp

- ↑ Brewer, P. G. and Bradshaw, A. 1975. The effect of non‐ideal composition of seawater on salinity and density. J. Mar. Res. 33: 157‐175

- ↑ Wright, D.G., Pawlowicz, R., McDougall, T.J., Feistel, R. and Marion, G.M. 2011. Absolute Salinity, “Density Salinity” and the Reference-Composition Salinity Scale: present and future use in the seawater standard TEOS-10. Ocean Sci. 7: 1–26

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|