Impact of tourism in coastal areas: Need of sustainable tourism strategy

This article discusses the current status of coastal tourism, the associated issues and impacts. The article further provides recommendations for future management of coastal tourism.

Contents

Introduction

Since the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, there is increasing awareness of the importance of sustainable forms of tourism. Although tourism, one of the world largest industries, was not the subject of a chapter in Agenda 21, the Programme for the further implementation of Agenda 21, adopted by the General Assembly at its nineteenth special session in 1997, included sustainable tourism as one of its sectoral themes. Furthermore in 1996, The World Tourism Organization jointly with the tourism private sector issued an Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry, with 19 specific areas of action recommended to governments and private operators towards sustainability in tourism.

On the other hand, an analysis of the sustainability policies, strategies and instruments of 21 European countries revealed a gap between good theoretical approaches and the general willingness to support a sustainable tourism development and the realisation of it, and concluded that in hardly any of the countries is sustainable tourism put in the centre of the national tourism policy as a priority area[1].

Specific situation of coastal areas

Coastal areas are transitional areas between the land and sea characterized by a very high biodiversity. They include some of the richest and most fragile ecosystems on earth, like mangroves and coral reefs. At the same time, coasts are under very high population pressure due to rapid urbanization processes. More than half of today’s world population live in coastal areas (within 60 km from the sea) and this number is on the rise.

Additionally, among all different parts of the planet, coastal areas are those which are most visited by tourists and in many coastal areas tourism presents the most important economic activity. In the Mediterranean region for example, tourism is the first economic activity for islands like Cyprus, Malta, the Balearic Islands and Sicily.

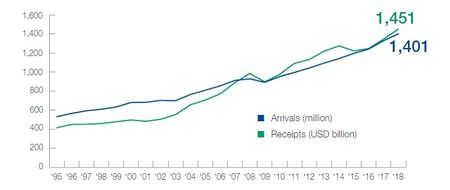

Forecast studies carried out by WTO in 2000 estimated that international tourist arrivals to the Mediterranean coast would amount to 270 millions in 2010 and to 346 millions in 2020. However, the latter figure was reached already in 2015 [2].

Causes of coastal degradation

Tourisms often contributes to coastal degradation. There are many other causes:

- Coastal zone urbanization

- Fisheries and aquaculture

- Port development and shipping

- Land reclamation

- Land-use conversion (Agriculture, Industrial development)

- Climate change and sea level rise

See also Threats to the coastal zone.

How does tourism damage coastal environment

Massive influxes of tourists, often to a relatively small area, have a huge impact. They add to the pollution, waste, and water needs of the local population, putting local infrastructure and habitats under enormous pressure. For example, 85% of the 1.8 million people who visit Australia's Great Barrier Reef are concentrated in two small areas, Cairns and the Whitsunday Islands, which together have a human population of about 130,000.

Tourist infrastructure

In many areas, massive new tourist infrastructure has been built - including airports, marinas, resorts, and golf courses. Overdevelopment for tourism has the same problems as other coastal developments, but often has a greater impact as the tourist developments are located at or near fragile marine ecosystems. A few examples:

- mangrove forests and seagrass meadows have been removed to create open beaches;

- tourist developments such as piers and other structures have been built directly on top of coral reefs;

- nesting sites for endangered marine turtles have been destroyed and disturbed by large numbers of tourists on the beaches.

Careless resorts, operators, and tourists

The damage is not only due to the construction of tourist infrastructure. Some tourist resorts empty their sewage and other wastes directly into water surrounding coral reefs and other sensitive marine habitats. Recreational activities also have a strong impact. For example, careless boating, diving, snorkeling, and fishing have substantially damaged coral reefs in many parts of the world, through people touching reefs, stirring up sediment, and dropping anchors. Marine animals such as whale sharks, seals, dugongs, dolphins, whales, and birds are also disturbed by increased numbers of boats, and by people approaching too closely. Tourism can also add to the consumption of seafood in an area, putting pressure on local fish populations and sometimes contributing to overfishing. Collection of corals, shells, and other marine souvenirs - either by individual tourists, or local people who then sell the souvenirs to tourists - also has a detrimental effect on the local environment.

The case of cruise ship tourism

Cruise ship tourism is a fast growing sector of the tourism industry during the past decades. While world international tourist arrivals in the period 1990 – 1999 grew at an accumulative annual rate of 4.2%, that of cruises did by 7.7%. In 1990 there were 4.5 million international cruise arrivals which had increased to a number of 8.7 million in 1999 and to 27 million in 2019, with gross economic benefits estimated at $150 billion in direct, indirect and induced economic benefits[3][4]. From the 1980s to 2018, the global cruise fleet grew from 79 to 369 vessels operating worldwide, and the average cruise ship size and capacity grew from 19.000 to 60.000 gross registered tonnage (GRT). Carrying on average 4,000 passengers and 1,670 crew, these enormous floating towns are a major source of marine pollution through the dumping of garbage and untreated sewage at sea, and the release of other shipping-related pollutants.

Issues

Problems caused by cruise tourism are ubiquitous and well-documented, especially for small island nations and the Mediterranean[5][6].

- Discharge of sewage in marinas and nearshore coastal areas. The lack of adequate port reception facilities for solid waste, especially in many small islands, as well as the frequent lack of garbage storing facilities on board can result in solid wastes being disposed of at sea, and being transported by wind and currents to shore often in locations distant from the original source of the material.

- Coral reefs. Land-based activities such as port development and the dredging that inevitably accompanies it in order to receive cruise ships with sometimes more than 3000 passengers can significantly degrade coral reefs through the build-up of sediment. Furthermore, sand mining at the beaches leads to coastal erosion. In the Cayman Islands damage has been done by cruise ships dropping anchor on the reefs. Scientists have acknowledged that more than 300 acres of coral reef have already been lost to cruise ship anchors in the harbour at George Town, the capital of Grand Cayman.

- Socio-cultural impacts. Cruise-ship tourism can produce socio-cultural stress, since it means that during very short periods there is high influx of people, sometimes more than the local inhabitants of small islands, possibly overrunning local communities. Vital resources such as food, energy, land, water, etc. may become depleted.

- Ship emissions. Fuel-based cruise ships currently produce large amounts of greenhouse gases. The gradual replacement is only now starting. From the approximately 100 new builds planned up to 2027, one-fifth are LNG powered, corresponding to 39% of the new tonnage and 41% of the added capacity[7].

Cruise tourism is often ascribed as hedonistic. However, a positive effect of expedition cruise tourism is its educational and awareness-creation potential for sustainability values and issues. It can transform a ‘sense of place’ to a ‘care of place’, encouraging tourists and locals to assume more responsibility[8].

Impacts of coastal tourism

Environmental impacts

- The intensive use of land by tourism and leisure facilities

- Overuse of water resources, especially groundwater, leading to soil subsidence and saline intrusion

- Changes in the landscape due to the construction of infrastructure, buildings and facilities

- Vulnerability to natural hazards and sea level rise

- Pollution of marine and freshwater resources

- Energy demand and consumption

- Air pollution and waste

- Disturbance of fauna and local people (for example, by noise)

- Loss of marine resources due to destruction of coral reefs, overfishing

- Compaction and sealing of soils, soil degradation due to overuse of fertilizers and loss of land resources (e.g. desertification, erosion)

- Loss of public access

Impacts on biodiversity

Tourism can cause loss of biodiversity in many ways, e.g. by competing with wildlife for habitat and natural resources or by providing pathways for the introduction of alien species. Negative impacts on biodiversity are caused by various other factors, such as those mentioned above.

Socio-cultural impacts

Change of local identity and values:

- Commercialization of local culture: Tourism can turn local culture into commodities when religious traditions, local customs and festivals are reduced to conform to tourist expectations and resulting in what has been called "reconstructed ethnicity".

- Standardization: Destinations risk standardization in the process of tourists desires and satisfaction: while landscape, accommodation, food and drinks, etc., must meet the tourists expectation for the new and unfamiliar situation. They must at the same time not be too new or strange because few tourists are actually looking for completely new things. This factor damages the variation and beauty of diverse cultures.

- Adaptation to tourist demands: Tourists want to collect souvenirs, arts, crafts, cultural manifestations. In many tourist destinations, craftsmen have responded to the growing demand and have made changes in the design of their products to make them more attractive to the new customers. Cultural erosion may occur in the process of commercializing cultural traditions.

Cultural clashes may arise through:

- Economic inequality - between locals and tourists who are spending more than they usually do at home.

- Irritation due to tourist behaviour - Tourists often, out of ignorance or carelessness, fail to respect local customs and moral values.

- Job level friction - due to a lack of professional training, many low-paid tourism-jobs go to local people while higher-paying and more prestigious managerial jobs go to foreigners or "urbanized" nationals.

Benefits of Sustainable coastal tourism

Economic benefits

The main positive economic impacts of sustainable (coastal) tourism are: contributions to government revenues, foreign exchange earnings, generation of employment and business opportunities. Employing over 3.2 million people, coastal tourism generates a total of € 183 billion in gross value added and represents over one third of the maritime economy of the European Union. As much as 51% of bed capacity in hotels across Europe is concentrated in regions with a sea border[10].

Contribution to government revenues

Government revenues from the tourism sector can be categorised as direct and indirect contributions. Direct contributions are generated by income taxes from tourism and employment due to tourism, tourism businesses and by direct charges on tourists such as ecotax. Indirect contributions derive from taxes and duties on goods and services supplied to tourists, for example, taxes on tickets (or entry passes to any protected areas), souvenirs, alcohol, restaurants, hotels, service of tour operators.

Foreign exchange earnings

Tourism expenditures, the export and import of related goods and services generate income to the host economy. Tourism is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38 % of all countries.

Employment generation

The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. Tourism can generate jobs directly through hotels, restaurants, taxis, souvenir sales and indirectly through the supply of goods and services needed by tourism-related businesses (e.g. conducted tour operators). Tourism represents around 7 % of the world’s employees. Tourism can influence the local government to improve the infrastructure by creating better water and sewage systems, roads, electricity, telephone and public transport networks. All this can improve the standard of living for residents as well as facilitate tourism.

Contribution to local economies

Tourism can be a significant or even an essential part of the local economy. As environment is a basic component of the tourism industry’s assets, tourism revenues are often used to measure the economic value of protected areas. Part of the tourism income comes from informal employment, such as street vendors and informal guides. The positive side of informal or unreported employment is that the money is returned to the local economy and has a great multiplier effect as it is spent over and over again. The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) estimates that tourism generates an indirect contribution equal to 100 % of direct tourism expenditures.

Direct financial contributions to nature protection

Tourism can contribute directly to the conservation of sensitive areas and habitats. Revenue from park-entrance fees and similar sources can be allocated specifically to pay for the protection and management of environmentally sensitive areas. Some governments collect money in more far-reaching and indirect ways that are not linked to specific parks or conservation areas. User fees, income taxes, taxes on sales or rental of recreation equipment and license fees for activities such as hunting and fishing can provide governments with the funds needed to manage natural resources.

Competitive advantage

More and more tour operators take an active approach towards sustainability. Not only because consumers expect them to do so but also because they are aware that intact destinations are essential for the long term survival of the tourism industry. More and more tour operators prefer to work with suppliers who act in a sustainable manner, e.g. saving water and energy, respecting the local culture and supporting the well-being of local communities. In 2000 the international Tour Operators initiative for Sustainable Tourism was founded with the support of UNEP. In 2014 it merged with the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC).

Environmental Management and Planning benefits

Sound and efficient environmental management of tourism facilities and especially hotels (e.g.water and energy saving measures, waste minimization, use of environmentally friendly material) can decrease the environmental impact of tourism. Planning helps to make choices between the conflicting interests of industry and tourism, in order to find ways to make them compatible. Planning sustainable tourism development strategy at an early stage prevents damages and expensive mistakes, thereby avoiding the gradual deterioration of the quality of environmental goods and services significant to tourism.

Socio-cultural benefits

Tourism as a force for peace

Travelling brings people into contact with each other. As sustainable tourism has an educational element it can foster understanding between people and cultures and provide cultural exchange between guests and hosts. This increases the chances for people to develop mutual sympathy, tolerance and understanding and to reduce prejudices and promote the sense of global brotherhood.

Strengthening communities

Sustainable Coastal Tourism can add to the vitality of communities in many ways. For example through events and festivals of the local communities where they have been the primary participants and spectators. Often these are refreshed, reincarnated and developed in response to tourists’ interests.

The jobs created by tourism can act as a very important motivation to reduce emigration from rural areas. Local people can also increase their influence on tourism development, as well as improve their jobs and earnings prospects through tourism-related professional training and development of business and organizational skills.

Revitalization of culture and traditions

Sustainable Tourism can also improve the preservation and transmission of cultural and historical traditions. Contributing to the conservation and sustainable management of natural resources can bring opportunities to protect local heritage or to revitalize native cultures, for instance by regenerating traditional arts and crafts.

Encouragement social involvement and pride

In some situations, tourism also helps to raise local awareness concerning the financial value of natural and cultural sites. It can stimulate a feeling of pride in local and national heritage and interest in its conservation. More broadly, the involvement of local communities in sustainable tourism development and operation seems to be an important condition for the sustainable use and conservation of the biodiversity.

Benefits for the tourists of Sustainable Tourism

The benefits of sustainable tourism for visitors are plenty: they can enjoy unspoiled nature and landscapes, environmental quality of goods or services (clean air and water), a healthy community with low crime rate, thriving and authentic local culture and traditions.

Sustainable Tourism Strategy

The sustainable management of tourism is a complex managerial undertaking, requiring the involvement of multiple stakeholder groups, at local, regional and international levels. It entails a large set of actors and stakeholders, ranging from tour operators, industry associations and NGOs to local public authorities, businesses and independent small vendors. Indirectly, ‘producing holiday experiences’ involves entire communities and is subject to a multiplicity of motives, interests and perspectives[7]. In other words, the tourism economy consists of an entire network of institutional and business actors, that should be engaged in sustainable practices through rules and incentives.

Below a few steps are listed for the development and implementation of a strategy for sustainable tourism.

Analysis of status-quo

- Analysis of previous tourism management strategies for the specific area: What can be used? Has it been implemented? Which lessons are to be learnt?

- A stakeholder analysis: Who has an interest in sustainable tourism development? Who are the main actors?

- Facts and figures of the local educational system, economic and social structure

- Anecdotal and traditional knowledge

This information can be collected through

- Interviews with stakeholders

- Questionnaires distributed and collected by e-mail, fax or personally in order to compile standardised data and perform a statistical analysis

- Participation in focus group meetings (e.g. meetings on environmental education, biodiversity management, good governance and fisheries)

- Literature search (including the local library)

Strategy development

A Sustainable Tourism Strategy is based on the information collected. It defines the priority issues, the stakeholder community, the potential objectives and a set of methodologies to reach these objectives. These include:

- Conservation of specific coastal landscapes or habitats that make the area attractive or protected under nature conservation legislation

- Development of regionally specific sectors of the economy that can be interlinked with the tourism sector (e.g. production of food specialities and handicrafts)

- Maximising local revenues from tourism investments

- Enabling self-determined cultural development in the region, etc.

Action plan

The Action Plan describes the steps needed to implement the strategy and addresses a number of practical questions such as: which organizations will take up which activities, over what time frame, by what means and with which resources? As the actions have to be considered on the basis of regional circumstances, there is no standard action plan for all. However, Action Plans usually include measures in the following fields:

- Administration: e.g. promotion of co-operation between sectors and of cross-sectorial development models; involving local people in drafting tourism policy and decisions

- Socio-economical sector: e.g. promoting local purchasing of food and building material; setting up networks of local producers for better marketing; development of new products to meet the needs of tourists, etc.

- Environment: e.g. improving control and enforcement of environmental standards (noise, drinking water, bathing water, waste-water treatment, etc.); identification and protection of endangered habitats; creation of buffer zones around sensitive natural areas; prohibition of environmentally harmful sports in jeopardised regions; strict application of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment procedures on all tourism related projects and programs

- Knowledge: training people involved in coastal tourism about the value of historical heritage; environmental management; training protected area management staff in nature interpretation; raising environmental awareness among the local population; introducing a visitors information programme (including environmental information)

Conclusions

During the last century, the role of beaches has completely reversed: they have become the driving force behind economic welfare instead of just being an inhospitable place. Demographic pressure, excessive land use and related factors, both in the hinterland (e.g. river dams, water diversion) and on the beach itself (e.g. hard coastal protection structures, sand/coral mining), have led to a general decrease in the contribution of sediments to the maintenance of the beaches and foreshores. It is hard to find a unique solution for all those problems. However, the following points are essential:

- The implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management

- A better dissemination of the existing information should be achieved. For that purpose, a better coordination of the existing governmental bodies that deal with coastal management is necessary

- Improvement of environmental education is a precondition for sustainable development of the coast

See also

External links

https://www.gstc.org/ The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) is managing the GSTC Criteria, global standards for sustainable travel and tourism; as well as providing international accreditation for sustainable tourism Certification Bodies.

Internal Links

References

- ↑ Dickhut, H. and Tenger, A. (eds.) 2022. Review and Analysis of Policies, Strategies and Instruments for Boosting Sustainable Tourism in Europe. European SME Going Green 2030 Report, p. 505

- ↑ UNWTO

- ↑ https://www.f-cca.com/downloads/2018-Cruise-Industry-Overview-and-Statistics.pdf 2018 Cruise Industry Overview]

- ↑ Papathanassis, A. 2022. Cruise tourism. In D. Buhalis (ed), Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 687–690

- ↑ Moscovici, D. (2017) Environmental Impacts of Cruise Ships on Island Nations, Peace Review, 29: 366-373

- ↑ Caric, H. and Mackelworth, P, (2014) Cruise tourism environmental impacts – The perspective from the Adriatic Sea. Ocean & Coastal Management. 102: 350-363

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Papathanassis, A. 2023. A decade of ‘blue tourism’ sustainability research: Exploring the impact of cruise tourism on coastal areas. Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures 1: 1–11

- ↑ Walker, K. and Moscardo, G. 2016. Moving beyond sense of place to care of place: The role of indigenous values and interpretation in promoting transformative change in tourists’ place images and personal values. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 24: 1243–1261

- ↑ International Tourism Highlights (2019) https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152

- ↑ Ecorys (2016) Study on specific challenges for a sustainable development of coastal and maritime tourism in Europe EC Maritime Affairs

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|