Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)

Definition of Integrated Coastal Zone Management:

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) is a resource management system following an integrative, holistic approach and an interactive planning process in addressing the complex management issues in the coastal area [1].

See also Some definitions of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)

This is the common definition for Integrated Coastal Zone Management, other definitions can be discussed in the article

|

The concept of Integrated Coastal Zone Management was borne in 1992 during the Earth Summit of Rio de Janeiro. The policy regarding ICZM is set out in the proceedings of the summit within Agenda 21, Chapter 17. The European Commission defines ICZM as “a dynamic, multidisciplinary and iterative process to promote sustainable management of coastal zones. It covers the full cycle of information collection, planning (in its broadest sense), decision making, management and monitoring of implementation. ICZM uses the informed participation and cooperation of all stakeholders to assess the societal goals in a given coastal area, and to take actions towards meeting these objectives. ICZM seeks, over the long-term, to balance environmental, economic, social, cultural and recreational objectives, all within the limits set by natural dynamics. 'Integrated' in ICZM refers to the integration of objectives and also to the integration of the many instruments needed to meet these objectives. It means integration of all relevant policy areas, sectors, and levels of administration. It means integration of the terrestrial and marine components of the target territory, in both time and space”[2].

Coastal zones can generate great prosperity for society and therefore exert a strong attraction for settlement and for the development of economic activities. The societal benefits of coastal zones are often referred to as ecosystem services. The location at the interface of land and sea implies highly dynamical interactions, both of natural and social processes with strong feedbacks between the two. This also makes coastal zones vulnerable and therefore requires careful management that takes into account the many interdependencies and developments in the short and long term.

Current coastal zone management practices are often different. In many cases, structural, legal or institutional adjustments are only made after a disaster has occurred. These adjustments often focus on addressing the most pressing issues without a well-considered long-term strategy. Integrated Coastal Zone Management is aimed at preventing (or reducing the impact) of disasters and promoting sustainable development of the coastal zone, taking into account diverse interests and possible futures.

Contents

The specific character of coastal zones

A well-informed science-based coastal zone management strategy embedded in an adequate social, institutional and legal framework, can prevent many future coastal problems. This is now usually called ICZM, Integrated Coastal Zone Management. As far as the technical aspects are concerned, experienced coastal authorities are capable to overview most of the coastal engineering issues associated with the future developments of the coastal zone. However, ICZM requires a broader view of coastal issues. ICZM is a governance process for the coastal zone, which differs from usual territorial governance processes due to its specific characteristics:

- The coastal zone has no fixed administrative boundary; it is defined by the environmental (physical, ecological) interaction processes between the land environment and the marine environment that evolve over time.

- The coastal zone usually has no single entrusted government; coastal zone governance is an interplay of several local, regional and national institutions with different mandates and responsibilities.

- The coastal zone environment (the physical and ecological state) is highly dynamic due to the interaction processes between the land environment and the marine environment.

- The coastal zone offers important ecosystem services with a much wider geographical significance.

- Settlements in low-lying coastal zones are very vulnerable to extreme climatic events and to the impact climate change (see Coastal cities and sea level rise).

Because of these particular characteristics many studies and experiments have been carried out for defining a coherent ICZM governance process for coastal zones. Studies and experiments for developing and implementing ICZM are listed in the category Integrated Coastal Zone Management.

Why it is difficult to put ICZM into practice

| Prejudice / impediments for ICZM |

|---|

|

Lack of public awareness: “People tend to underestimate risks of natural hazards” |

The problems with which coastal zones are confronted often have an insidious character, such as ongoing urban or touristic development, saline intrusion, decline of biodiversity or climate change and sea level rise/land subsidence. When problems are perceived as urgent the situation is often already irreversibly deteriorated. Who feels responsible for a well-balanced future-proof development of the coastal zone? At national level, coastal management responsibilities are divided over ministries serving different (and often competing) societal interests, such as public safety, infrastructure, nature, water, physical planning, housing, fisheries, agriculture, tourism, industry and cultural heritage. Local governments are often the only bodies responsible for weighing and integrating different interests. But the means to do this are limited, because often the situation is that:

- local authorities can be overruled by sectoral authorities on a higher governance level (region, state);

- local authorities have little or no staff with profound knowledge of the complex interactions that take place in the coastal zone;

- local authorities have limited financial resources for monitoring and assessment of the state of the coast and for restoration measures;

- local authorities have limited manpower and willingness to enforce regulations;

- The local interests that local authorities represent are often short-term interests.

Such obstacles to putting ICZM into practice can be overcome, at least in part, by delegating more powers to local authorities and by promoting public participation and involvement of civil society organizations (NGOs) in coastal policy processes. Public participation is most effective when the focus is on coastal management at the local level, as communities are directly affected by the consequences. At regional and national scales, attempts to involve the general public usually yield disappointing results, as this requires participants to acquire sufficient knowledge of complex underlying issues, including technical aspects[3]. It is also essential that ICZM is firmly anchored at a high political level and that institutions with widely accepted legitimacy play a leading role in the implementation, see Introduction of public participation. Ultimately, decisions must always be endorsed by authorities with an electoral mandate.

Other factors that can frustrate the implementation of ICZM are illustrated in Table 1. In almost every country, at least some of these factors (and possibly also others) constitute barriers to the implementation of ICZM. Identifying and tackling such barriers is a prerequisite for effective and successful ICZM.

ICZM implementation

The natural and social characteristics of different parts of the coastal zone can be highly diverse. Coastal zone policy can therefore be determined only partly at the national level. The primary focus at the national level is to establish a legal, institutional and administrative framework for integrated coastal zone management. Of crucial importance is the institutional embedding of the ICZM process. The institutional framework must provide the mandate and resources for the local implementation of ICZM. Implementation of ICZM requires that sufficient powers be delegated to local authorities. This can be a problem in countries with a strongly centralized governance culture.

The coastal zone is constantly evolving through natural and socio-economic processes. ICZM should therefore not consist of a one-time static plan or as a series of ad hoc actions, but must be shaped as a continuous process that goes through an established policy cycle according to the schedule:

Plan development => Implementation => Monitoring => Evaluation => Plan revision => Implementation => Monitoring => Evaluation, etc.

This cycle is implemented at both local and national level:

- At local level, detailed concrete plans are developed and carried out (after endorsement at the national level) in consultation with all local and national stakeholders;

- At national level, national objectives and targets are defined, local plans are integrated in a national strategy and mandate and resources are allocated for implementation.

The cycle period should be adjusted to the rate at which developments take place in the coastal zone. A cycle of one year may be too short; a cycle of 5 years or 10 years can be more appropriate. The cycle period at the local level may be shorter than at the national level.

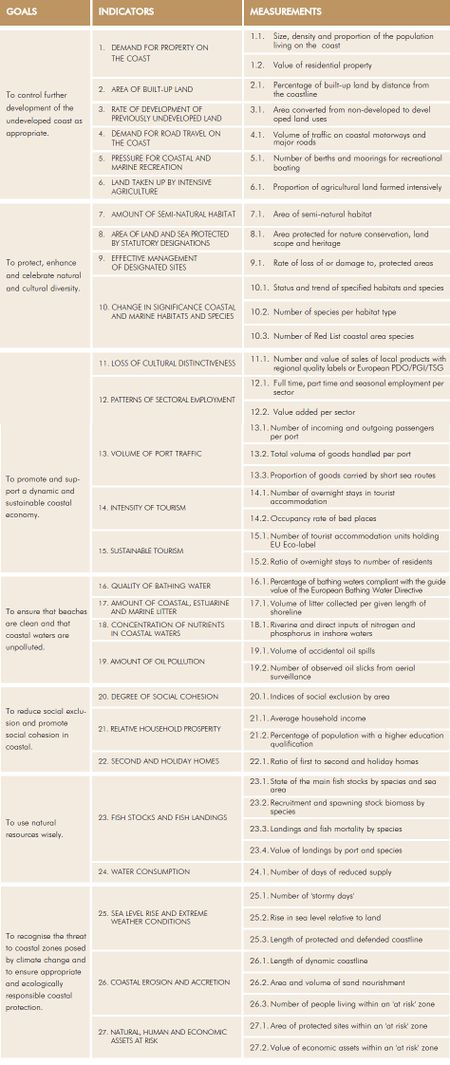

Monitoring and evaluation are essential process steps to determine which progress has been realized in the implementation of the ICZM plan. This is only possible if measurable indicators and quantitative targets have been defined for this purpose. Defining indicators and targets is a major component of the ICZM plan process. Various examples of ICZM indicators have been described in the literature. ICZM indicators proposed by Marti et al. (2007) [4] are shown for illustration in Table 2. Successful implementation of ICZM is highly dependent on the definition and monitoring of adequate indicators and targets. See also the article Sustainability indicators.

Institutional arrangements

In small countries with a homogeneous coastal zone (natural and socio-economical), local and national level can coincide. This will not be the case for large countries with very diverse coastal zones. Both at local and national level, sufficient expertise must be available to implement the ICZM policy cycle. At the national level, a coordinating ministry must be designated that steers the policy cycle at the national level. This coordinating ministry should have internally sufficient general ICZM expertise to coordinate coast-related policies of other ministries and be capable to mobilize expertise of public and private organizations on specific topics. At the local level, a department of local government is responsible for implementation. The staff of this local department should have expertise in the fields of planning, communication, organizing public participation, administrative and technical implementation aspects and cooperation with private parties.

Complex infrastructural works and works that transcend the local scale do not fit within the aforementioned scheme. The steering of design and implementation in these cases lies with institutions at national level that are mandated for this and possess the required expertise.

The issue of climate change, which has far-reaching consequences for low-lying coastal areas, in many cases exceeds the local scale in terms of extent and complexity. A national adaptation strategy will be leading here for the development of adaptation measures on a local scale, see the Coastal Wiki article Climate adaptation policies for the coastal zone.

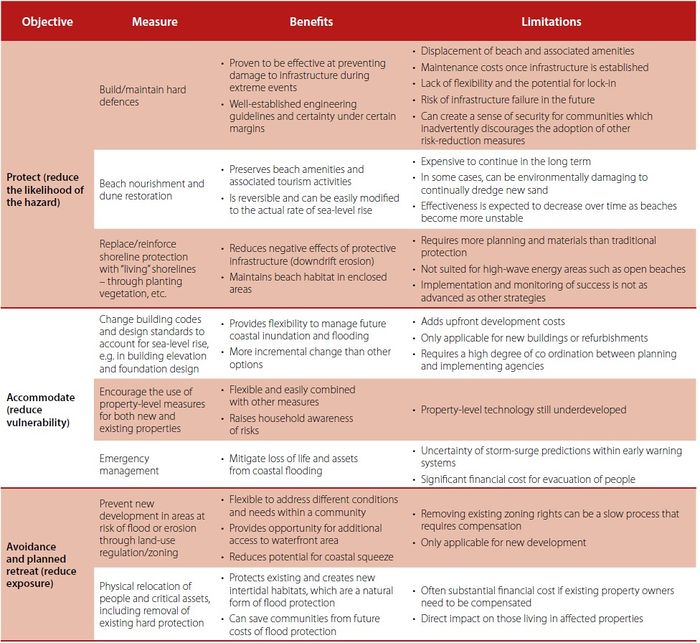

ICZM fields of action

Coastal zone management requires action in many areas related to legal, institutional, social, economic and environmental aspects. The coastal zone is not a passive system; every intervention will cause a reaction. Depending on the nature of the intervention, a response from the natural system (evolution towards a new equilibrium) and / or a social response can be expected. The final outcome of the intervention strongly depends on these responses. Therefore, not only excellent planning and engineering expertise is required, but also in-depth knowledge of the natural (physical, biological, chemical) dynamics of the coastal system and a full understanding of the social, economic, legal, institutional and political context. Examples of factors that must be taken into consideration when planning coastal protection measures are indicated in Table 3.

Major objectives of ICZM are related to:

- Protecting people and assets at risk

- Enhancing sustainability and ecosystem services

- Economic development of the coastal zone

- Creating awareness of coastal zone vulnerability and risks

- Good governance

A large number of actions must be considered to achieve these objectives. An overview of such actions is given in Table 4. A more detailed description of several actions is provided in Coastal Wiki articles that can be accessed by clicking on the internal (blue) links.

| General objective | Specific objective | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Protecting people and assets | Flood risk reduction |

Shoreline management plan and implementation |

| Emergency rescue |

Early warning system and organization | |

| Flood prevention |

Soft measures: | |

|

Hard measures: | ||

| Erosion mitigation |

Soft measures: | |

|

Hard measures: | ||

| Enhancing sustainability and ecosystem services | Natural protection |

Structural measures: |

|

Planning: | ||

| Sediment management |

Sand by-pass systems | |

| Limitation of soil subsidence |

Regulations for groundwater extraction and drainage and for extraction of minerals | |

| Climate change adaptation (CCA) |

Climate projections and socio-economic scenarios for the future | |

| Economic development | Land-use (housing, agriculture, fisheries) |

Ban on urban development in sensitive zones |

| Tourism |

Attractive landscape and cultural heritage | |

| Port and industry |

Ban on industrial development in sensitive zones | |

| Awareness raising | Public information and consultation |

Dissemination of local of risk maps |

| Financial instruments |

Coastal risk insurance | |

| Governance | ICZM policy cycle |

Planning-monitoring-assessment cycle implemented at decision-making levels |

| Legal/institutional framework |

Clear responsibilities endorsed by all concerned administrations | |

| Knowledge base |

Monitoring and assessment organization |

Towards integrated policy making

The table above illustrates the great diversity of issues to which coastal management is confronted. Management approaches often focus on single issues and on interventions that can yield fast results with the least amount of effort[9]. This approach of harvesting the low-hanging fruit often relies on specific local technical or administrative solutions. It has obvious merits, but generally does not tackle the fundamental roots of many problems. Underlying causes often touch upon societal core values - traditions, culture, distribution of welfare, commercial interests and lifestyle (such as use of short-lived and non-recyclable goods, use of scarce or non-renewable resources, living by the sea, ..). Moreover, many local issues cannot be solved in isolation because they are intertwined with global issues, such as demographic growth, social equity, public health, pollution, resource depletion and climate change. Tackling the fundamental underlying issues is generally harder and results are in general not readily apparent, but there is no good alternative.

One way to make progress towards integrated policy making is to define concrete physical, environmental and socio-economic development targets for the status of the coastal zone in the future (e.g. 20 or 50 years) and to identify possible evolutionary paths for their realization. This makes clear what first steps are needed now and in the near future and provides a justification that promotes social and political acceptance. This procedure, sometimes called back-casting[10] or reverse engineering, is akin to the strategy of adaptive pathways for climate adaptation, described in the article Climate adaptation policies for the coastal zone. An example of such an approach are the objectives for the environmental status of the coastal zone imposed by the European Habitats Directive and the Water Framework Directive. Another example is the target to limit global warming to 1.5 oC and the path to zero net greenhouse gas emissions agreed in the Paris climate agreement.

See also

General introductions to theory, practice and tools for ICZM can be found in the articles:

- Some definitions of Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)

- The Integrated approach to Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)

- Policy instruments for integrated coastal zone management

- ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES FOR INTEGRATED COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT

- Sustainability indicators

- Vulnerability and risk

- Shoreline management

- Multifunctionality and Valuation in coastal zones: concepts, approaches, tools and case studies

- Multifunctionality and Valuation in coastal zones: introduction

- Climate adaptation policies for the coastal zone

- Climate adaptation measures for the coastal zone

- Coastal cities and sea level rise

- Governance policies for a bio-based blue economy

- Groundwater management in low-lying coastal zones

Other Coastal Wiki articles related to Integrated Coastal Zone Management are listed under the category Integrated coastal zone management.

Further reading

There is a comprehensive bibliography on ICZM. A selection of useful documents is indicated below.

Website European Commission with information about EU strategy (EU recommendation on ICZM of 30 May 2002 (2002/413/EC)) and ICZM information platforms. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/iczm/rec_imp.htm

Report on the state of the environment in the coastal areas of Europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eea_report_2006_6

Assessment of European coastal erosion policies in relation to ICZM (Conscience project 2010). http://www.conscience-eu.net/documents/deliverable11-assessment.pdf

Cummins, V., O Mahony, C., & Connolly, N. 2004. Review Of Integrated Coastal Zone Management & Principles Of Best Practice. https://www.ucc.ie/research/crc/papers/ICZM_Report.pdf

US National Coastal Zone Management Program. https://coast.noaa.gov/czm/

IOC 2006. A handbook for measuring the progress and outcomes of integrated coastal and ocean management. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, Manuals and Guides, 46; ICAM Dossier, 2. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000147313

DEFRA 2008. A strategy for promoting an integrated approach to the management of coastal areas in England. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. http://www.greeninfrastructurenw.co.uk/climatechange/doc.php?docID=154

OURCOAST database (2011) with lessons learned from the coastal management experiences and practices in European countries. https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/metadata/portals/ourcoast-the-european-portal-for-integrated-coastal-zone-management

References

- ↑ Thia-Eng, C. 1993. Essential elements of integrated coastal zone management. Ocean and Coastal Management 21:81-108

- ↑ COM(2000) 547 final

- ↑ Guyot-Téphany, J.G., Davret, J., Tissière, L. and Trouillet, B. 2024. Public participation in marine spatial planning in France: From minimal requirements to minimal achievements. Ocean and Coastal Management 256, 107310

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martí, X., Lescrauwaet, A-K., Borg, M. and Valls, M. 2007. Indicators Guidelines To adopt an indicators-based approach to evaluate coastal sustainable development. Deduce project, Department of the Environment and Housing, Government of Catalonia. https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/metadata/tools/deduce-indicators-guidelines-to-adopt-an-indicators-based-approach-to-evaluate-coastal-sustainable-development

- ↑ OECD, 2019, Responding to Rising Seas: OECD Country Approaches to Tackling Coastal Risks, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/environment/cc/policy-highlights-responding-to-rising-seas.pdf

- ↑ Wilby, R.L. and Keenan, R. 2012. Adapting to flood risk under climate change. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133312438908

- ↑ Spalding, M.D. et al. 2014. The role of ecosystems in coastal protection: Adapting to climate change and coastal hazards. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.OCECOAMAN.2013.09.007

- ↑ Harman, B.P. et al. 2015. Global lessons for adapting coastal communities to protect against storm surge inundation. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-13-00095.1.

- ↑ Riechers, M., Brunner, B.P., Dajka, J-C., Duse, I.A., Lübker, H.M., Manlosa, A.O., Sala, J.E., Schaal, T. and Weidlich, S. 2021. Leverage points for addressing marine and coastal pollution: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 167, 112263

- ↑ Dreborg, K.H., 1996. Essence of backcasting. Futures 28: 813–828

Please note that others may also have edited the contents of this article.

|